Wimself Pt. III

By Josh Siegel

WIMSELF pt. III

By Josh Siegel

Photography by Wim Wenders

A candid and freewheeling conversation in four parts with Wim Wenders, the poet laureate of New German Cinema

![<I>True Vibe, Vitória, Brazil</i>, 2013]() True Vibe, Vitória, Brazil, 2013

True Vibe, Vitória, Brazil, 2013![<I>Window Painting, Brazil</I>, 2008]() Window Painting, Brazil, 2008

Window Painting, Brazil, 2008![<I>In Eastern Germany, Goerlitz</I>, 2006]() In Eastern Germany, Goerlitz, 2006

In Eastern Germany, Goerlitz, 2006![<I>The Old Jewish Quarter, Berlin,</I>, 1992]() The Old Jewish Quarter, Berlin,, 1992

The Old Jewish Quarter, Berlin,, 1992![<I>Written In The West 01</I>, 1980s]() Written In The West 01, 1980s

Written In The West 01, 1980s

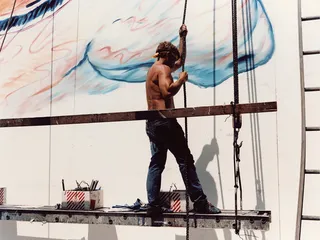

painting & peace

Wim Wenders: At one crossroads of my life, I had to decide whether to be a painter or to move into the land of movies. Ever since, I have a burning heartache whenever I enter a painter’s studio, and I have lots of painter friends. It seems such a peaceful life! Even for Francis Bacon, the studio seems such a refuge of peace. Looking at paintings in a museum is the thing that grounds me the most. Painting has this inbuilt propensity to remind us what peace is. The act of painting is an act of creating peace.

Josh Sielgel: Why did you feel painting and movies were mutually exclusive and you couldn’t pursue both?

I totally objected to the idea of doing something as a hobby.

Why did it have to be a hobby?

Because you have to be painting all the time. Like Anselm Kiefer—he’s a compulsive painter. When he wakes up at night, he gets into his slippers and walks down to the studio to paint.

But I think of certain filmmakers—take Pier Paolo Pasolini, David Lynch and Julian Schnabel, for example—who have that kind of peaceful space that you’re describing. They need to be in their solitude, painting, when not collaborating on a movie with so many others.

I’ve found that space in photography, but a painter’s studio is even more concentrated, like a place outside of time. I like visiting painters just to sit there, smell it, feel and be witness to how time stretches out.

As a friend of certain painters, I’m moved by their unquenchable sense of curiosity and discovery. Even late in life, painting always seems to remain a mystery. They’re still trying to figure out how colors work, how form works. Think of Monet, coping with blindness and old age by painting water lilies. In doing so he gives birth to modernism.

Whatever you do as a painter, it always starts with a blank canvas. As a filmmaker, you never have that blank canvas. Maybe at the beginning of a shoot, when you set up your camera and you really don't know how the film is going to go. But as a painter, you always start with an empty canvas.

You’ve often spoken of the ways in which music, a particular song, informs so much of your filmmaking. Do you also think about specific painters when considering the look or the locations or the nature of a character for each film? Obviously Edward Hopper has had a big influence on you.

In the very beginning, that was the case, yes. Robby [Müller, cinematographer] and I would start a film with painters and photographers as models. Walker Evans was the model for Kings of the Road [1976]. Edward Hopper for The American Friend [1977].

And Paris, Texas [1984]?

Paris, Texas was the first film where we did not do storyboarding or sketches or decide on a shot list in the evening. Robby and I consciously didn’t want to be prepared—rather, letting the landscape determine the first shot. That was the greatest challenge of Paris, Texas. From beginning to the end, we had that rule: no preconceived setups. Setups would strictly come out of a sense of place.

And what about the locations? Had you done much of that before you set out to—

I had an abundance of locations because I had done three months of traveling in the West. I knew every dust road. I had so many choices. When we ran out of script and didn’t know how to end the film—Sam Shepard and I sort of desperately had to figure out the last third of Paris, Texas because Sam was way up north shooting Country [1984]—I suddenly remembered a border town between Texas and Louisiana, Port Arthur. I had gone to Port Arthur because that’s where Janis Joplin went to high school and I wanted to see it. Port Arthur was a godforsaken place. There I discovered the Keyhole Klub. It was abandoned, a former nightclub. I saw the interior and thought it was extremely interesting. I forgot all about it until I was looking for a way to end the movie. I came upon the photographs of the Keyhole Klub in Port Arthur, and that’s where it clicked. I wrote the scenes for this imaginary peep show, sort of a reinvention of that idea. It came out of a memory of a place.

Did you shoot it in Port Arthur or did you construct a set?

Only the exterior, when he walks into the house, but we had to build these cabins. Nothing like that existed, especially not with the semitransparent mirror between the girls and the customers.

Did you and Shepard have specific locations in mind when you first wrote the script?

We wrote for a nondescript desert border area near Mexico. I saw every little town along the Mexican border and eventually ended up in Big Bend. I did that without Sam. The plan was that he’d be on the shoot with me so we could write the ending together. But he was so much in love with Jessica Lange that he decided to do Country, and that’s why I started with only half a script. Sam was not with us in the beginning, but Big Bend was exactly the border territory we had in mind. We shot in incredible towns like Marathon and Terlingua.

chocolate & matcha

Alice Ice, 1973

Chocolate and matcha. These belong in the addiction category.

Here’s the real test, though: What kind of chocolate?

Seventy-five percent.

Thank God. I was hoping you wouldn’t say milk chocolate. Seventy-five percent is pretty high in cocoa.

Donata’s territory starts at 75 and goes up to 100. For me, 100 is like eating dust, like grabbing a handful of dust and putting it into your mouth.

And matcha?

Matcha is a new addition to my addictions. It happened lately, in Japan. [An aside] Where is my matcha? The waiter took it and didn’t bring us a new one. Anyway, I’m also the original Cookie Monster.

But not cake.

Not really.

Pie?

Cheesecake sometimes can be good.

Apple pie?

Apple crumble with whipped cream, yes. I eat the whole thing if it’s in front of me.

Ice cream?

Ice cream, yes. Ice cream is missing from my list. My go-to is dark chocolate. I’ve had my aberrations. Like in America, for a while I had to have rocky road. I loved the whole almond-and-marshmallow idea. But I got off the rocky road because it’s too sweet.

You’re off the rocky road? Literally, metaphorically?

Off the rocky road in many senses. I love Italy because of the quality and variety of the ice cream. Shooting in Palermo was heaven.

William Hurt and Chishū Ryū in Until the End of the World, dir. Wim Wenders, 1991

The COOKIE MONSTER

Dinosaur and Family, California, 1983; Hamburger, Texas, 1983

The Cookie Monster is a dark story in my life. I was making my second movie, The Scarlet Letter [1973], out of Munich. There was a party one night with lots of friends and I hadn’t eaten. I opened the fridge and there was a bowl of cookies. They tasted good. I was alone in the kitchen. I smoked a cigarette and ate some more. And then in came the host, who saw the situation and went pale. “You did not.” The bowl was half empty. “You did not.” He was already on the phone calling the ambulance.

Pot cookies.

Yes. A single one for each party guest, and I had eaten 30. At the hospital they pumped my stomach, but my heartbeat was at 220, which was pretty dangerous. A half dozen young doctors were looking down at me, not knowing how to help. I made a conscious peace with my life. I knew that this was it. I had a near-death experience then, when I passed out. I was very clear, thinking that if only my parents knew how beautiful it is to die, they wouldn’t have to worry just because they lost a son. I went through a tunnel into a white light, and in that white light I thought again, “If only I could let them know that there is nothing to be afraid of!” And then I disappeared in the whiteness and eventually woke up and was in a hospital room. Surely that ugly hospital room couldn’t really be it. My girlfriend was asleep, so I woke her up. She was so happy I made it. But I felt a strange disappointment.

After that, it was a bad time in my life, panic-driven. I was deeply afraid and couldn’t control the fear. Eventually I was on tranquilizers, but one doctor said, “The only thing that can help you is psychoanalysis. We can pump you full of stuff, but we can’t control those fears.” That got me to start a psychoanalysis, and that really saved my life.

Where were you in The Scarlet Letter at that time, a film I know you dislike?

I was editing. Peter [Przygodda], my editor, was with me in the ambulance, and I told him exactly what to do to finish the fucking film.

I’m struck by the white light and the tunnel. It seems like such a cliché.

But it’s totally that! The fact that so many people report the same thing means there’s something to it.

It seems somehow Jungian, this commonality to all the experiences.

Yes, to experience something that you’ve heard before and then to experience it as something extremely vivid—it’s the loss of any fear.

Do you remember it like it was yesterday, even now?

I can always evoke it right away. I can remember it as a way to calm down or fight anxiety whenever I’m in a situation when things go berserk. At the time it had the opposite effect, just overwhelming. But the psychoanalysis—talking, talking, talking—was the best antidote to all that.

New York Breakfast, 1973

“I’m eternally grateful to psychoanalysis because it strengthened my identity.”

How many days a week were you going?

This is remarkable! I came upon a guy called Dr. Marseille. If you look into the history of Sigmund Freud, you see pictures of him with his first class in Vienna. In the first row, the young man on the far left was my Dr. Marseille. He was a direct student of Freud.

He must’ve been pretty old by the time you—

He was 80 and that was a problem. We did two, two and a half years, five days a week. I did my movies during his holiday time.

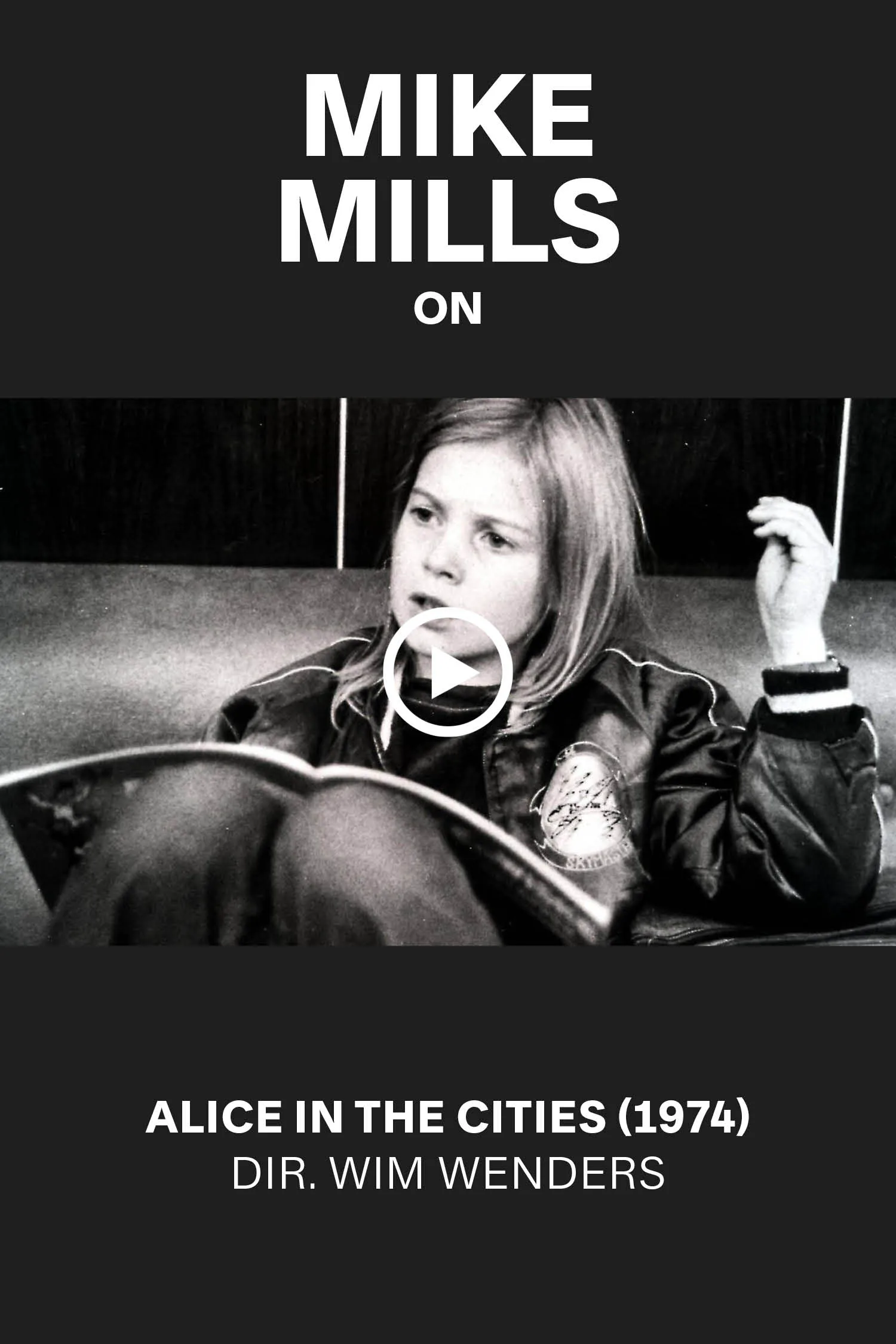

You had just begun psychoanalysis when you were working on Alice in the Cities [1974]?

Yeah, shot during his holidays. We had a pretty tough schedule because we shot it in three weeks, maybe four, and then I was back in Munich. One day I knocked as always, the door didn’t open, and I went home a little troubled. Maybe he fell asleep. Came back the next day and knocked. Nothing. I became alarmed. The next day it opened and a little old lady said, “My brother died.” Shock! I realized that I wasn’t finished and I couldn’t leave it at that. It took me a while to find somebody who would take over. I found a young man. We did three and a half more years and then mutually declared it finished. We embraced each other, really hugged each other, and never saw each other again.

Amazing that you were one step removed from Freud. Our mutual friend Jeanne Moreau once told me that her therapist was Jacques Lacan himself. “And?” I asked, my jaw slackening. And in Jeanne’s usual coy way, she grinned and said, “Well, that’s between me and Lacan.”

I’m very happy that the young doctor and I finished the whole thing and came to a satisfying conclusion. I wrote him a couple of postcards but never got a reply. As it’s supposed to be. But it did save my life—I can honestly say that. And I would be a different person if I had not done it. I’m eternally grateful to psychoanalysis because it strengthened my identity.

driving

.jpg)

Flat Tire 03, Monument Valley, 1977

Driving. Drive, He Said. When I got my driver’s license on my 18th birthday, my father said, “I’d rather not have you drive my Citroën DS.” That was his proudest possession. “I’ll buy you a car. A used car.” An uncle of mine was a Citroën dealer. He had a used Deux Chevaux that my father bought for a thousand bucks. My father said, “The deal is, I’ll buy you that car, but you have to shake hands with me that you will never in your life ride a motorcycle”—because he was a surgeon and specialist in bone structures and structural damage, and ever since the war had been nailing and sawing off body parts and screwing them back together. So we shook hands and I never, ever in my life did ride a motorcycle. I’ve seen lots of friends get into bad accidents. Even on a shoot of mine, Kings of the Road, the key grip had an accident and broke his leg.

So your first car was a Deux Chevaux? With those little lawn chairs for seats?

Yes, and the flap-up windows. I was smoking Gauloises and it was a 13-horsepower car. I did cross the Alps in it. On steep serpentines it just couldn’t go anywhere anymore. Even in first gear, it would come to a grinding stop. And I was about to abandon the Alps when somebody stopped and said, “I know your problem. I had a Deux Chevaux myself. You can’t do it in the first gear, but you can do it in reverse.” So I crossed the Alps backwards.

That’s hilarious.

My 13 horsepowers also took me to Africa. I drove through France, Spain, through Gibraltar, to Ceuta. Great car. I had three Deux Chevaux over the years. Afterward I became a filmmaker and advanced to my father’s beloved DS.

Where is it now?

It was stolen in Munich. It was a white DS, the good one with the bigger engine, not the 19 but the 23. It was a beautiful car, but it was stolen. The police wanted to know if I could describe anything in particular so they could maybe find it. I remembered there was one thing that no other DS would have, and it was the front tooth of little Alice from when we shot Alice in the Cities. She had given it to me and I had put it as a good luck charm over the door where there was a strange little bend.

But they never found the car?

Never. I bought another used DS with the insurance money. Now French people drive the DS as an electric car. That is a dream for me. Also, after my Deux Chevaux, I first had the gangster car, the Traction Avant, the black postwar Citroën. I made my short film Alabama [1969] with it.

It’s interesting that your dad would have a French car in the land of German engineering.

This was so extravagant. My dad, a doctor in a small town in the Ruhr district, where every other doctor was driving a Mercedes. The Citroën was his proudest possession, an ID19. The day it arrived, all the neighbors came running and photographed it, and it was the talk of the town. And I was proud of my father. I never thought he would dare drive such an extravagant car in a little town in Germany. My mother always got sick in that car because the suspension was so soft.

Tell me about your choice of cars for your films.

The most extravagant was a Rover Coupé I acquired when we were making The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick [1972]. It was a beautiful car, with red leather seats, three-and-a-half liter engine. It got ruined on a slippery road in the winter when I drove onto a traffic island and broke the frame. That was the end of it. And the other extravagant one was that old Citroën Traction Avant, the long version, and that made it into two films. I had a beautiful car in America, an Oldsmobile Delta 88 convertible that shows up in The State of Things and other films.

I think of that beautifully lit scene inside the car with Allen Garfield in The State of Things.

That was [cinematographer] Henri Alekan’s masterpiece. We shot all this on location and had a rack with 20 lamps around, on top of the car. It was—how do you call them?—a mobile home. We were driving at night on Sunset Boulevard, 20 times or more up and down. Henri sat in the back seat with an organ of faders and orchestrated the lights. The car also looked fantastic from the outside, like a driving light show. Henri had done this kind of lighting onstage but never in life, in a car on location. He was sitting in the back of that car like a happy kid with his toys.

You once told me something that has stayed with me, that you’re always mistrustful of period films where all the cars seem brand new. Because that’s not how people live, that’s not what a street full of cars would look like. You want dusty cars, cars with dents, to give a sense of verisimilitude, right?

Can’t stand those clean cars. I think it’s live or die for a period movie for the cars to be believable. And then if you see any of these period movies, you’ll realize they always use the same 10 cars in every scene of the film. When a car goes past, you realize it’s the one that you saw parked in the previous shot! It drives me crazy. And for the few period movies I did, I must say, it’s hard to deal with the people who own the cars because they never want them dirtied up.

Selecting the cars for your so-called road movies must have been a weighty decision, no?

Also the most fun decisions. It took us four weeks to find the truck for Kings of the Road. It had to be a beat-up old truck but still be drivable and safe. The truck we found traversed the whole German border twice without breaking down. It had 15 gears with a clutch, and Rüdiger [Vogler] had to learn to drive it. It was a science, but he did it heroically. None of us ever learned it. He was more occupied with driving the bloody truck than with his part as an actor.

Baseball Match 02, California, 1970s

You put a lot of pressure on him. It’s not easy to go from gear to gear while also trying to remember or make up your lines.

But the choice of cars, it’s very important. The other day I saw Jean-Luc Godard’s Le petit soldat [1963] again. The dialogue specifies to have every car mentioned by maker and year. An amazing array of cars, and he manages that the audience gets to know each and every one of them by name.

That’s very funny. I always think of Weekend [1967], of course, as Godard’s car film. But you’re right about Le petit soldat. I believe it’s also Claire Denis’s favorite Godard.

It is a fabulous film, underrated. He made it in 1960, right after Breathless, and then it didn’t come out for three years, because the French censored it.

With the war raging in Algeria.

Exactly. The film was very critical of the French army in the war. When it came out a year after the war had ended, it was already dated and therefore overseen somehow.

Did you see it when it came out in 1963?

I saw it in Paris a few years later, because it was at a reduced ticket price in one of those theaters where you pay and see the film again and again. It must have been in ’66.

As for other cars in your films, what about Lisbon Story [1994]?

Lisbon Story has a Citroën CX Break in the opening sequence that breaks down on the road. We had to sell it in Lisbon because we couldn’t fix it anymore. What else? I famously have a few VW Beetles. In The American Friend, for instance, a beautiful red VW. And that same red VW appears in Paris, Texas. And in the opening scene of Kings of the Road, a Beetle drives straight into the river Elbe.

That unforgettably beautiful shot in The American Friend of the VW driving on the beach.

Yeah, Bruno Ganz’s character, Zimmermann, dies in it. In Paris, Texas, Travis’s brother, Walt, has that VW in his garage and little Hunter hides in it. So I’ve had my share of Beetles.

That red in particular—were you thinking of Ozu’s use of red? That specific red is very—

No, that was before I ever saw an Ozu film. It’s very much a Coca-Cola red. In Until the End of the World, there are a lot of science-fiction cars. And Solveig’s character is driving my Rover Coupé. She’s driving, anachronistically, this 1970s Rover Coupé in the future. The one she crashes. That was painful because the car was useless after that.

maps

![]()

New York First Impressions, 1972

![]()

New York Postcard, 1972

Maps were always a big thing in my life. My father had this encyclopedia, the Brockhaus, the German equivalent to the Britannica. It had 20 thick volumes. As my parents were poor, they didn’t have any other picture books. But the Brockhaus was full of pictures. I was drawn, of course, to every reproduction of art in it, but also to the maps, how they unfolded. I understood the world this way. There was also a big atlas from my grandfather. I spent hours and hours studying maps. I knew the names of countries that no other kids my age had ever heard of. My infatuation with stamps started that way as well. I collected stamps from countries that other people didn’t even know existed.

Do you still have your stamp collection?

Yeah, I still have the entire thing. It was once worth a lot, in my mind at least, now practically nothing. There is no market anymore, nobody’s interested anymore.

How old were you when you got on your first plane?

My very first plane was while shooting Summer in the City [1971]. I was a student. I went from Munich to Berlin because the second part of the film takes place in Berlin. That was the first time I set foot on a plane. Before, I had always traveled by car or by train. Then I was the first of my friends or family to go to America. In 1972. Icelandair via Reykjavík, to get to the first New Directors/New Films at MoMA for my first screening ever in the U.S., with The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick.

Did you return to Reykjavík?

The year afterward, to prepare Alice in the Cities. The plane lost an engine on the way from Luxembourg to Reykjavík, and we spent three days stuck there. I rented a car as soon as I heard that the plane wasn’t going anywhere. It was the only rental car they had. Everybody else had the same idea, but I had the car. And I crisscrossed Iceland for three days. In my Polaroid book, a lot of Polaroids are from Iceland, from that adventure.

.jpg)

Not much doing down here, Las Vegas, 1983

the desert

.jpg)

Dust Road, West Australia, 1988

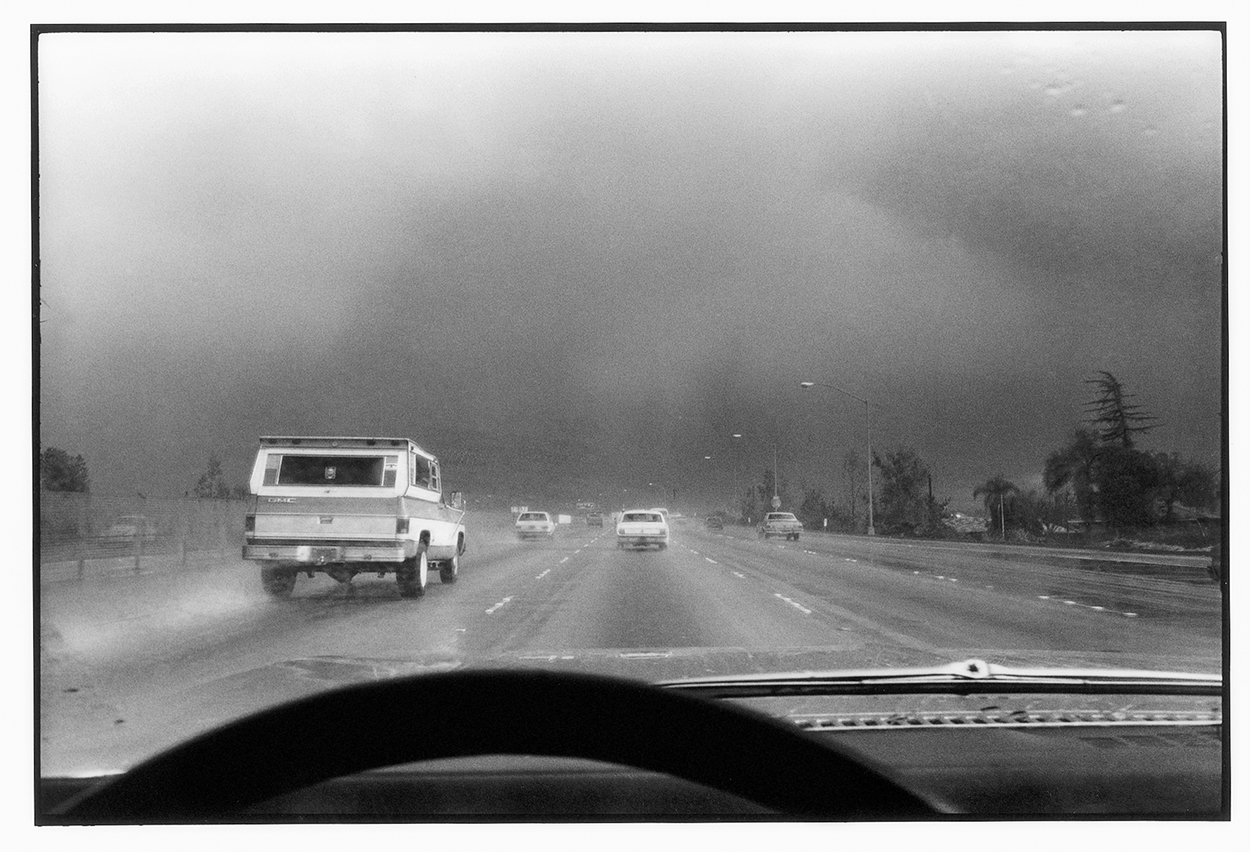

Driving and maps and the desert are related. Because “driving” is not really about driving in cities but about long-distance driving, long stretches of unknown road where you decide on your own if you go left or right. You check the map. Which place has the better name? I like having an itinerary based solely on names. Sawtooth Mountains, or Truth or Consequences: I just had to go there. And driving long hours, finding a motel and staying there not because you prebooked it but because it has a great neon sign that says “Vacancy.” You get a room, you have your car parked out front. Nothing to do there but be bent over the map all night long, to think where you can go the next day—based on names. Great!

You once made the point that, at least for the road movies, 90 percent of the time was spent in cars just getting to the location where you were going to shoot. This was especially true in the remote locations you used in the Australian Outback for Until the End of the World. Hours spent in cars, looking at the landscape and listening to the music that would shape the story, the mood and the characters of your movie.

Especially in Australia, where changing locations meant being on the road for two days, heading to places where nobody had ever been, certainly no tourist, like the Bungle Bungle Mountains, driving on red dust roads and imagining where the movie could take you now.

Were you listening to cassette tapes?

Lots of compilations. This was a great, fantastic culture for doing your own storytelling inside the storytelling of musicians and albums.

It was also the way to seduce girls when I was growing up. You’d make them compilation tapes. I remember how frustrated I would get. I did all the math to get the songs to fit on each side of the tape, but I would miss by, like, eight seconds and have to start all over. But it was worth it, even when I didn’t get the girl.

These compilations were love letters indeed. You could say so much through the songs, and through the order of songs, you could tell a story about who you were. All that is gone with digital playlists.