The Interpreter: Agnès Godard

By Yonca Talu

Agnès Godard on the set of A Greek Type of Problem, 2011

the interpreter

Agnès Godard’s cinematography of devotion

By Yonca Talu

July 1, 2023

From operating the camera on Wim Wenders’s Wings of Desire (1987) to lensing most of Claire Denis’s films, Agnès Godard has established herself as an essential, transformative voice in modern cinematography. Blending technical prowess and a raw, intuitive approach, her work qualifies as nothing less than visual poetry in Denis movies like Beau travail (1999) and Trouble Every Day (2001), whose tales of eroticism and violence Godard captures in kinetically vibrant, tactile images. In our conversation for Galerie in her Parisian home, the seasoned cinematographer reminisced about formative figures and experiences, including her introduction to filmmaking; her mentors Henri Alekan and Robby Müller; and her three-decade collaboration with Denis, the latest fruit of which is 2017’s incandescently shot, poignant Let the Sunshine In.

![]()

La Lumière sous la porte, dir. Agnès Godard, 1982

I recently watched La Lumière sous la porte [The Light Under the Door], a visually evocative short film you directed in 1982 as a tribute to your father, Jean Godard. I know how much of an inspiration he was to you, so I wonder if you could walk me through the personal journey that led you to dedicate a movie to him.

I grew up in the French countryside in the early ’50s. No one in my family had an artistic profession, but my father, who was a veterinarian, took a lot of pictures of us and the world around him. He photographed everything—flowers, cars, houses, people—in addition to shooting home movies, which he screened for us in the dining room. It was a marvelous ritual that made up for his reserved, taciturn personality, and triggered my fascination with images.

When I finished high school, I knew that I wanted to work in film, but my parents disapproved. Two of my brothers were doctors, so I was supposed to become a pharmacist, dentist or something like that. I managed to avoid a medical career and instead went to journalism school in Paris. Then I started a job at a PR agency, but I quit soon after to join the film studies program at Censier [Sorbonne-Nouvelle University].

There, I met some students from the IDHEC film school [now La Fémis], who offered me a part in their short movie. It was the first time I saw a studio, lights, a camera, and I was mesmerized. I thought, There’s no doubt this is what I want to do. So I decided to take IDHEC’s entrance exam and got into the cinematography department.

During my time at IDHEC, I realized that the roots of my attraction to cinema lay in my father’s photographs, and I began imagining a short film in tribute to him. Then, strangely and unexpectedly, reality surpassed fiction—my father died. I took up my script again and rewrote it, changing the setting from my family home and region to elsewhere. But I kept my initial idea of filming my dad’s photos. I received a state subsidy for my project and shot it after graduation.

I had also gotten some money from public television and the film was shown on TV. A few girls I went to high school with watched it and called my house to ask whether the director was the Agnès they’d known, because they thought the film resembled me!

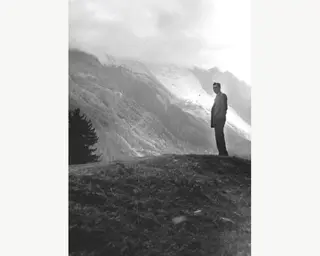

![]()

Jean Godard in Plateau d'Assy, France, 1956

That’s a lovely anecdote. It reminds me of the fact that your short film inspired both Claire Denis and Agnès Varda to collaborate with you. In that sense, it paved the way for your career as a cinematographer.

Yes, I can say that in retrospect. I met Claire Denis in the late ’70s through my ex-partner and the father of my daughter, who had worked alongside her as an assistant director. When I was preparing my short, I contacted her to ask for some advice. Later I invited her to the screening. She came up to me at the end and just said, ‘‘If I make a film one day, would you work with me?’’ There was something that undeniably appealed to her about my movie—perhaps the fact that it had no dialogue, I don’t know.

We crossed paths again when we both worked on Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas [1984] and Wings of Desire. She’d written her first feature, Chocolat [1988], and asked me to shoot it, but the producers refused because I had no experience as a director of photography. So I came on board as a camera operator on Chocolat, as well as on Claire’s following film, No Fear, No Die [1990]. [The TV documentary] Jacques Rivette: The Night Watchman [1990] was our first collaboration as director and cinematographer.

As for Agnès Varda, I worked with her on Jacquot de Nantes [Varda’s 1991 portrait of her husband, filmmaker Jacques Demy]. She had started shooting the movie with a friend of mine, Patrick Blossier, who was also the DP on my short. Production came to a halt because of Demy’s health, and when it resumed, Patrick was no longer available. He told Varda that he would find someone to replace him and suggested me. I hadn’t done anything yet as a DP, so to convince her, he showed her my short. She liked it and hired me for Jacquot de Nantes, which became my first feature as cinematographer.

It’s funny how one thing led to another. Back then I had said to myself, ‘‘When I make my short film, I’ll be able to start working. I’ll leave the time of my father’s images and enter the time of my own images.’’

Your film also ends on that note, doesn’t it? The protagonist photographs the facade of the house she grew up in, and we see her as a little girl in the picture that flashes up on the screen. She literally leaves her childhood behind.

Right, but she steals her dad’s camera. [Laughs]

For the scene in which the protagonist looks at her father’s photographs, I had selected and filmed with a rostrum camera black-and-white pictures taken by, and of, my dad. When I went to the lab to see the result, I was alone in the screening room, and a photo of my father in silhouette, taken by my mother, came up on the screen. I had always seen that image in negative—it hadn’t been printed—and thought that my dad was in profile. But at that moment, I realized that he had actually looked at the lens. So it was as though he were looking at me, which gave me the impression of exchanging with him words that we’d never exchanged in his lifetime.

I can even show you that picture. [She gets up, finds it and shows it to me.] The fact that one can come eye-to-eye with a dead person in an image is something that has always fascinated me. It reminds me of Roland Barthes’s phrase [from his 1980 book Camera Lucida]: ‘‘[T]he Look […] if it traverses, with the photograph, Time […] is always potentially crazy.’’

Thirty years after my father passed away, I found out that he was proud of me for getting into film school. He trusted me and thought that I would be able to make something of myself. Deep down, that resolution, or epiphany, was contained for me in my short film.

He gave you his approval.

Yeah. You could almost say he gave me my vocation.

It’s interesting that you used a word with a religious connotation.

It’s true that it’s a religious or mystical word, but I think it echoes my relationship with images and the way I operate as a cinematographer. When I look through the camera to set up a shot, the question I ask myself is, Do I believe what I’m seeing for the sake of the film? It has to do with devotion and a certain kind of faith in the power of cinematography. There’s a spiritual quest, so to speak.

That’s why my collaboration with Claire Denis has lasted so long. We’re very different people with very different personalities, but she also has a powerful spiritual connection with images.

“IT HAS TO DO WITH

DEVOTION AND A

CERTAIN KIND OF FAITH

IN THE POWER OF

CINEMATOGRAPHY.”

Did that shared spiritual sensibility inform the making of a film like Beau travail?

Certainly. When we arrived in Djibouti [where Beau travail is set], I thought, Oh là là! This is either the beginning or the end of the world. There was nothing but the earth, the sky, rocks, volcanoes, the sea and then the [legionnaire characters’] bare, athletic bodies, which made up the only raw material of the movie.

Even though we never said it to each other, Beau travail was quite an experimental film, and the fact that we didn’t see any of the rushes during the shoot made the whole experience even riskier. More than ever, it was a matter of making sure that Claire and I believed the same things and shared the same faith in images.

Prior to your collaboration with Claire Denis, you were a camera assistant and operator for three master cinematographers: Henri Alekan, Sacha Vierny and Robby Müller. What was it like to work with Alekan [who shot classics like Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast and William Wyler’s Roman Holiday]? How did he influence your approach to the craft?

In our last year at IDHEC, we had to work as DP on the films of three other students. One of them had asked to include in his budget a day or two of mentoring with a professional and had chosen Henri Alekan. That’s how I met and worked with Henri for the first time. I graduated a few months later but didn’t dare reach out to anyone to offer my services. One day, I received a call from IDHEC saying that Henri wanted to get in touch with me. They gave me his number, I called him and he asked me to be his assistant on Wim Wenders’s The State of Things [1982], which felt like a fairy tale.

My dad had recently died. So Henri, who was in his seventies and already part of film history, became somewhat of a spiritual father to me. It was really impressive to watch him work—he was technically very skilled but also very poetic, and as passionate about his craft as ever. I went to his house once and he said, ‘‘I’d like to show you something.’’ He took me to his study, pointed at a huge folder with scraps of paper sticking out from all sides and said, ‘‘Voilà, I wrote a book.’’ I replied, ‘‘That’s extraordinary, but wouldn’t you want me to type it up so that it becomes a document?’’ So I typed up Des lumières et des ombres [Of Lights and Shadows, Alekan’s 1984 reference book on cinematography].

For Henri, cinematography was not only something technical but also an element of mise-en-scène that participated in the storytelling. He thought that lighting and framing could be used to convey all kinds of psychological moods—tenderness, sensuality, fear, suspense, etc. I was very influenced by his approach. He helped me understand that a cinematographer is a fellow traveler, an interpreter to the director, and inspired me to rely on intuition as much as technique.

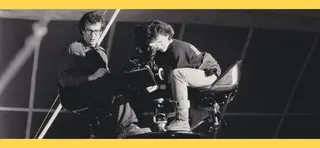

![]()

Agnès Godard and Robby Müller on the set of

Paris, Texas, 1983![]()

Agnès Godard and Claire Denis on the set of

Beau travail, 1998

How did you strike that balance between intuition and technique when you operated the camera for Alekan on a film as formally ambitious as Wings of Desire?

It was intimidating to be Henri’s camera operator on Wings of Desire but also a great opportunity. Wim is a man of images and had fully conceived the mise-en-scène. So all I had to do was interpret and embody the shots to the best of my ability.

But I do have an anecdote about the film that may relate to your question. Whenever we did an elaborate camera movement that ended on the angels [played by Bruno Ganz and Otto Sander], I would frame them in such a way as to leave a lot of room above their heads, because I wanted them to look like they were floating in the air. Wim, who saw the image on a monitor, kept telling me, ‘‘There’s too much headroom! There’s too much headroom!’’ I was embarrassed and terrified yet couldn’t help framing the angels that way!

A few years later, I worked on Amos Gitai’s Golem, the Spirit of the Exile [1992], my last film with Henri, in which Bernardo Bertolucci had a cameo role. We spent hours doing a complicated tracking shot with Bertolucci, who was impeccable in every take. At the end of the day, he came up to me and said, ‘‘You operated the camera on Wings of Desire, right? The headroom above the angels was so magical; I’d never seen such a thing before!’’

It must have been gratifying to hear that!

I was speechless.

What about the prolonged reaction shots of the angels? How did you experience filming those?

Wim wasn’t sure whether the angels would look into or off to the side of the camera, so we did a test shoot with Bruno Ganz where he tried both. When he looked into the camera, I said, ‘‘This is brilliant,’’ and it was chosen. I didn’t have any contact with Ganz during the actual shoot but spent the whole time telling myself that he was looking at me. Later, at the wrap party, he came up to me with a drink and said, ‘‘Here’s to you! We know each other well.’’

So you were right, he’d been looking at you!

Yes, it was extraordinary. He had played off me.

I was a very shy person, so looking at people behind the camera suited me quite well. One might think that’s voyeurism, and sometimes it can be. But this experience of actors looking back at the camera made me realize that being a cinematographer is more than just being a voyeur. It’s not about looking at people without their knowledge—it’s an exchange.

Did you feel even more connected with actors when you were doing over-the-shoulder camerawork on Claire Denis’s films?

Oh, yes. The first time I did over-the-shoulder on No Fear, No Die was exhilarating. I had the impression of being an unseen character in the film. I’d even suggested to Claire that the actors turn around sometimes and look at the camera. There are one or two moments where they can be spotted doing so.

What I love about over-the-shoulder is the feeling of framing not only with my eye but with my entire being. When you operate the camera on a dolly or crane, you’re aware of the frame and its edges, whereas when you operate on your shoulder—especially if you’re moving—you have a very central vision. You don’t have time to look at the edges of the frame, because if you do, you lose your rhythm and synchronization with the actors. It’s as if the camera were a magnet.

![]()

No Fear, No Die, dir. Claire Denis, 1990

Does your fondness for operating the camera on your shoulder have its roots in your collaboration with Robby Müller?

There was no over-the-shoulder in Paris, Texas, the film on which I was Robby’s assistant, but I owe many aspects of how I frame and hold the camera to him. I was very impressed with Robby as an operator. There was an obviousness to the way he chose the focal length, framed and panned that amazed me. He was at one with the camera, and I couldn’t tell whether he was directing or being directed by it.

That sounds similar to an actor’s process of inhabiting a role.

That’s true. Working with Robby taught me the importance of camera language: that putting the camera here has a different meaning than putting it over there. An image says something—it stems from a commitment, a thought.

You’ve said that Trouble Every Day [2001] was the first film on which you fully felt like a cinematographer.

It was the first time I felt like I’d managed to translate onto the screen the impressions I had while reading the script, which was very satisfying. Claire’s script contained evocative words that served as visual clues. For example, at the beginning, there was a description of an overripe fruit rotting in the garden of the house [where Alex Descas and Béatrice Dalle’s characters live]. That immediately gave me an idea as to how the film’s images should be—their color and texture had to suggest a sense of decomposition and death.

As inspiration for Trouble Every Day, Claire Denis showed you pictures by photographer Jeff Wall. How much did you draw from them to craft the film’s visual universe?

Looking at Jeff Wall’s pictures was like watching a movie. You found yourself imagining what might have happened before and what might follow. There was something very disquieting about them—a feeling of hovering menace that became a guiding thread for me. I thought there should be a similar anxiety in every image of Trouble Every Day.

Could you give an example of how you and Claire Denis injected anxiety into the images?

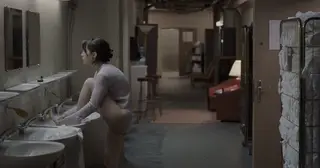

Take for instance the scene with the young maid in the hotel’s basement. We start with a wide shot of her standing in front of a row of sinks. She’s alone, wearing panties, and it’s a bit dark. She puts her foot in the sink, bends over and washes it. She’s in a fragile position yet seems comfortable and confident. Is she right to be so? I would have been scared.

Then we position the camera behind her. But we don’t just show her back—we fill the foreground with the side of a laundry cart to imply that someone might be hiding there and looking at her. There’s a sense of menace in these images.

![]()

Trouble Every Day, dir. Claire Denis, 2001

In the scene in which Alex Descas’s character buries his wife’s latest victim, there are striking close-ups of blood dripping from plants.

Those close-ups were edited into the scene you mentioned, but they were shot on the same night as an earlier scene—the one where Alex’s character discovers the corpse of a man eaten by his wife. Claire needed time to find her way into that sequence, so we began with close-ups of dripping blood to get inspired. She spoke about this once, saying, ‘‘The producers thought we were crazy to spend so much time on details rather than start working with the actors.’’ [Laughs]

Using a part to represent the whole is essential to Claire’s work. She finds images meaningful enough to constitute a sequence and trusts that it isn’t necessary to show anything more. That leaves space for viewers to fill in the blanks as they please.

Since the early 2010s, you’ve been shooting with digital cameras. How has transitioning from film to digital impacted your way of working?

My introduction to digital wasn’t easy. I struggled with the technology but also felt nostalgic for the texture of film images. I eventually came out of that nonconstructive state and decided to get acquainted with digital. I think I’m still in the process of discovering the medium, which has evolved a lot since then. There are terrific digital cameras today, but I’ve yet to find a way of working with them that suits me.

Weren’t you pleased with your work on Claire Denis’s Bastards [2013] and Let the Sunshine In?

Bastards was the first film I shot on digital that I was pleased with, but it’s only after finishing postproduction that I felt satisfied. During the shoot, I wasn’t sure I would be able to find the images I ended up finding.

Why?

Although digital is technically more capable than film, it doesn’t allow me the same freedom. With a film camera, I just had to look through the viewfinder to see the image I was making, whereas with a digital camera, I often have to look at a monitor. That induces a different way of framing and prevents me from being at one with the camera like I used to.

The intuition I had when looking through the viewfinder of a film camera was something I relied on a lot. Sometimes I would even ignore my light meter and set the exposure by eye. I wasn’t afraid of technique back then; now I’m a bit intimidated by it.

I recently did the digital restoration of Trouble Every Day and it was wonderful to work with film images again. The colorist at the lab was crazy about the movie and kept saying, ‘‘There’s so much freedom in these images!’’ That moved me a lot.

I used to think it would be nice to go back to shooting on film, but lately I’ve changed my mind. What I’d actually like to accomplish is to shoot a movie on digital on which I feel as free as I did with film. I don’t want to turn the clock back but rather find freedom again as a cinematographer.

Translated from French by Yonca Talu

![]()

Agnès Godard and Wim Wenders on the set of Wings of Desire, 1987