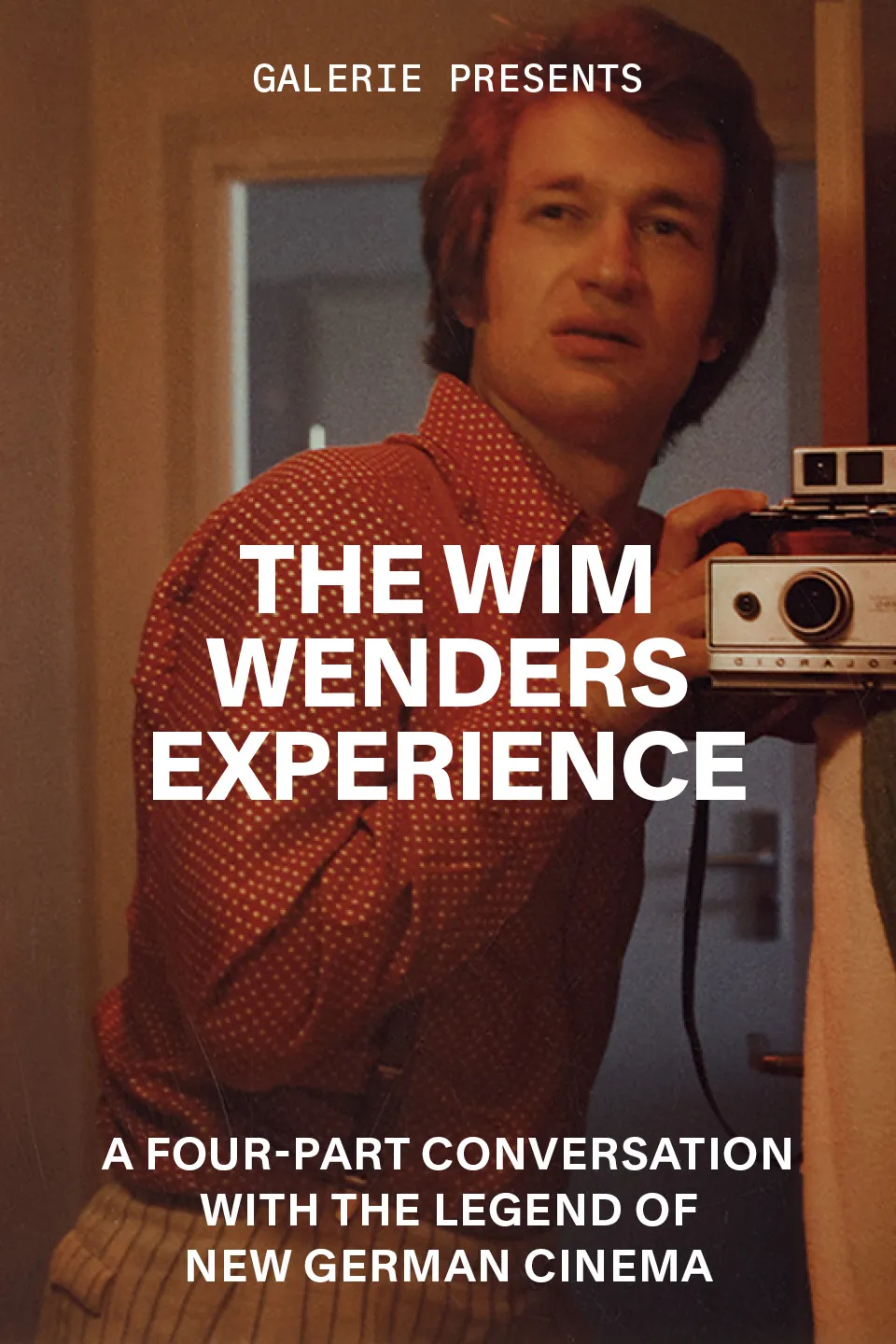

Wimself Pt. IV

Josh Siegel

Wimself Pt. IV

By Josh Siegel

Photography by Wim Wenders

A candid and freewheeling conversation in four parts with Wim Wenders, the poet laureate of New German Cinema

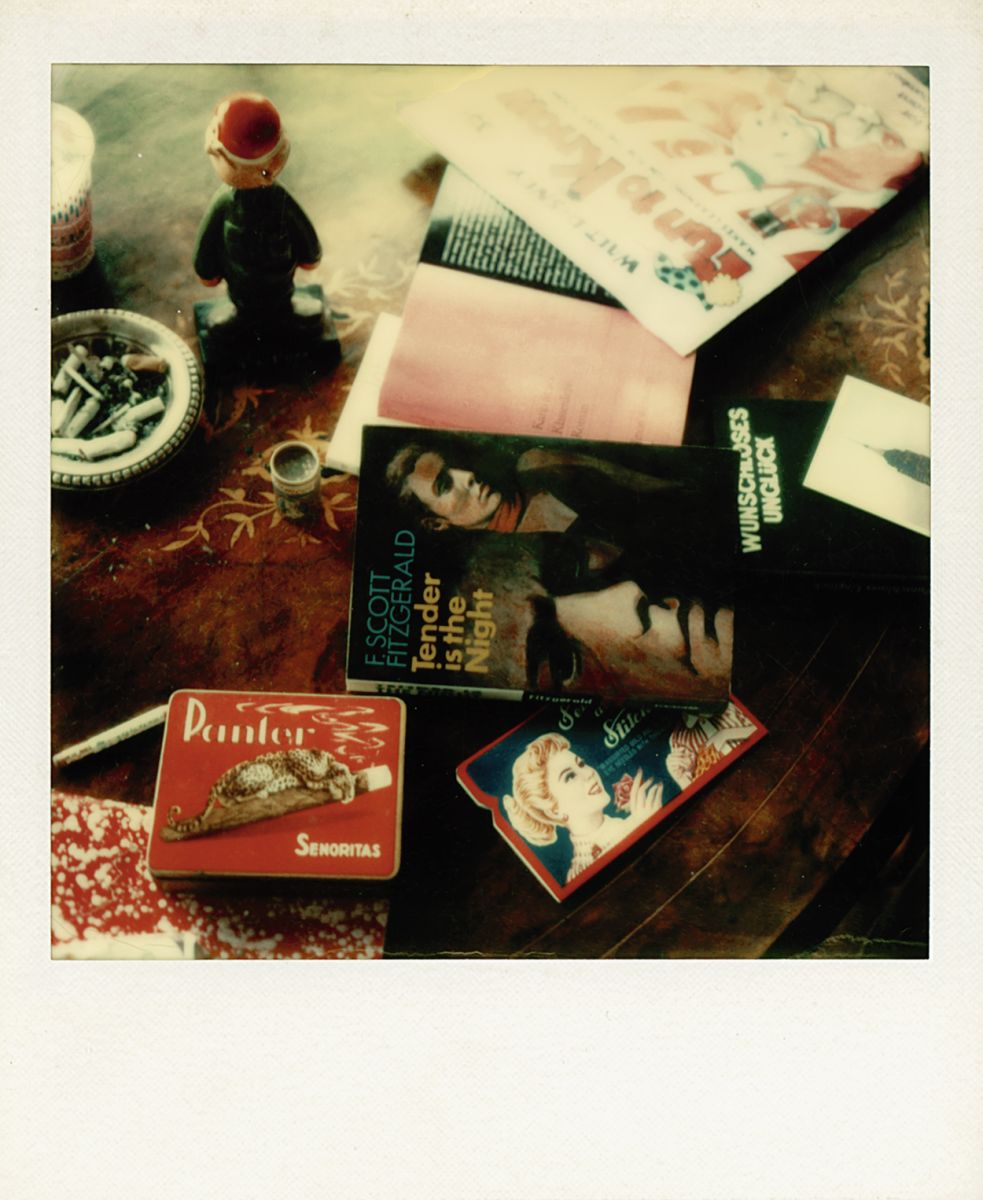

reading

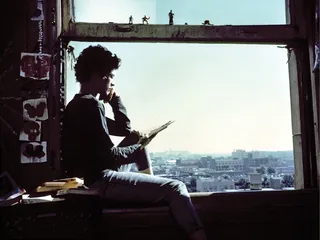

Alice in Instant Wonderland 06, 1973

Wim Wenders: The designated reader before I could read was my grandmother. I was firmly convinced she was just there to read for me. She was sort of a slow reader and not an intellectual person. Sometimes, I corrected her, but I learned to read following her finger.

Josh Siegel: How old were you?

I was five. But reading was big and I was soon reading a book a day. I was reading everything, but most of all the 50 or so volumes of Karl May.

The German author of popular Westerns. Were Westerns your first real introduction to American popular culture?

Yes, yes.

From Karl May, a guy who had never once been to the American West.

l read voraciously, all the books in the local library. The librarian was a good friend of mine, and at one point she just shrugged her shoulders. “I have nothing left for you. You read it all. You could go to the grown-up section.” I said, “Yes, why not?” She just made sure I didn't really get anything really—

Racy.

[Laughs] Racy could be dangerous for my young mind. I also read voraciously at night. Eventually I got very scared about my under-the-blanket reading habits. You see, I couldn’t afford the batteries—they were the old kind and wouldn’t last longer than half an hour. But l found something amazing: a rechargeable plate of phosphorus from my chemical set. If you lit it for one second, then you could read two pages under the covers. Later on, when my uncle gave me my first watch for my Communion, he said it was phosphorus [inside]. But when he added that it was dangerous, my heart sank. I worried I would get brain damage or die young because I had been exposed to an amazing amount of radiation. They don’t even make those watches anymore, let alone the phosphorus plates.

Do you find yourself returning to certain books as a grown-up?

I still read a lot of poetry. A few people I read in their entirety. I mean, there are my close friends. I know every book by Peter Handke. Those have accompanied my entire life, starting when he first published at 23 and I was 20. I’ve also read everything by Paul Auster. And Sam Shepard. Peter Carey is another one. I worked with him [on Until the End of the World, 1991] because I loved his books so much. Then there’s Dashiell Hammett. I know each and every line he ever wrote, even his stories in pulp magazines. I collected them all when I was preparing Hammett [1982]. Same with Chandler, Ross Macdonald, a certain number of crime writers. I still like Raymond Chandler—every 10 years I read all his stuff from scratch.

I always wonder why no one’s made a faithful adaptation of Hammett’s Red Harvest. Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo [1961], Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars [1964] and Walter Hill’s Last Man Standing [1996] were all inspired by what I think of as Hammett’s greatest novel, but there’s never been a literal retelling of the story.

Bertolucci and I were two who tried. I remember meeting Bernardo in a hotel room in downtown New York. He was working on his adaptation of Red Harvest and said, “I have been working on this for two years, but now the guy who owns the rights turns out to be an asshole who wants to mess with my script and I don’t think I want to make this movie with him.” Bernardo eventually gave up. I tried, when I did Hammett, to get in touch with that guy, but he immediately had so many conditions I gave up. I tried very hard in Hammett to at least make up scenes that would feel like Red Harvest, especially as I knew that Poisonville in the novel was Butte, Montana, where Hammett was a Pinkerton strikebreaker.

The novel is essentially about the unsolved murder of the labor leader Frank Little.

Exactly. I was in Butte, Montana, a dozen times. Photographed the hell out of it. Could have shot Red Harvest immediately from what was there, though it’s all changed now, unfortunately. I would still love to make Red Harvest. I was told that this year or next it’ll be in the public domain.

Before Martin Scorsese made Killers of the Flower Moon [2023], I often thought the one quintessential American genre he’s never tackled is the Western, and who better than him to adapt Red Harvest.

Because it would be a strange Western. It’s also a New York crime story. Anyway, I love the language of the book. Both Faulkner and Hemingway admit they knew and admired it. Then there’s the other American writer whose work was never turned into a film, Walker Percy.

Funny, I just reread The Moviegoer and wondered why it was never adapted.

Terrence Malick gave me a script of it, a beautiful script, which he abandoned after Hurricane Katrina. He said he couldn’t shoot it anymore, because most of the locations had disappeared. He worked on it for years and could never pull it off. For me, Percy is such an exemplary Southern writer. My favorite book is The Second Coming. It’s amazingly funny and light and beautiful and spiritual. You’ll laugh out loud when you read it. So that’s one of my reading dreams. But the first books that really were my own territory, at six or seven, were The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. That was a milestone of my life.

In English or German?

German. Much later I read them in English. I dreamed of those guys and their lives for so long. Huckleberry Finn and Tom were great figures of freedom. When I read The Last of the Mohicans as a boy, I loved it too. Anyway, reading is one of the essentials of traveling and driving and hotels and the desert. You have to have books with you.

games & playing

From left: Paris Front Lawn, Texas, 1983; On the Adriatic Coast, 1994; Tokyo Theme Park, 2008

We already touched on poker, which I abandoned after being pretty much on a roll. But I still love playing. With kids I play the stupidest games without stopping for hours. And I love Monopoly—such a silly game. I mean, I get obsessed by it and I’m very disappointed when other people don’t take it seriously. Some of my grandchildren are serious players and would never give up, so I like playing with them. Because games, you have to take them seriously.

Are you teaching them no-limit Hold’em?

No, no, don’t worry.

Were you an athlete growing up?

Yes, football [soccer]. And track and field.

Long distance or short?

Both. I did 100 meters in 11.2, which was pretty fast. My favorites were the 3,000 and 5,000. I ran a few 10,000s in school. Marathons came later. But I love all the short distances and relays, too. And for 20 years of my life, I was an obsessive tennis player. I played in all my free time. From 14 to 40. Playing on concrete finally ruined my knees. I still dream of tennis and my dangerous backhand—better than my forehand—and I had a good serve. I played in tournaments.

“I love Monopoly—such a silly game. I get obsessed by it and I’m very disappointed when other people don’t take it seriously.”

Sports don’t come up that much in your movies, except maybe The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick [1972]. Are you very competitive?

Sort of. Tennis is so beautiful because it is competitive without hurting anybody. Soccer, you can hurt each other. I played soccer with Werner Herzog on my team, and he just ran me over. He was going for the ball regardless of who had it. Werner was dangerous even on your own team. [Laughs] You didn’t want to play against him. But what a great guy he is!

He would take out his own teammates?

Oh, yeah, he wanted the ball. Werner was a ferocious player. Anyway, sports are not so great in movies. And The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick only has two minutes of playing. Watching sports events from the past is not so thrilling, but live it beats most movies.

Elvis Inn Jerusalem, 2000

trees

Trees are an important thing in my life. When I was young, we lived in a little neighborhood of Düsseldorf, close to the Rhine. There were wild trees near the river. The Rhine would flood these areas [in the spring], but in the summer I had the greatest adventures there. I got into tree climbing at the age of seven or eight. A friend and I climbed each and every tree in the area. The two of us were fearless. My parents never knew about that obsession. I’ve had a very beautiful relationship with trees ever since. I started to read about how trees communicate. When Donata and I looked for a place in the country, it had to have an old tree close to the house. We found one with a 200-year-old tree, a mighty ash tree, close to our barn. Together we can just barely reach around it.

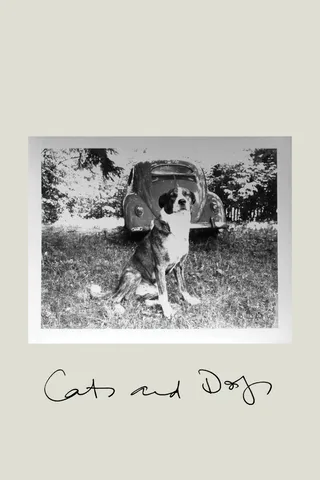

cats & dogs

![]()

DCK Location, Montana, 2005

![]()

Traktor, 1970s

I’m not a cat person as opposed to a dog person. I love both. I had Toby the cat and Traktor the dog at the same time. They were the best of friends. Toby would sleep within Traktor’s legs. If you offered Traktor a cookie, he looked down like, “I can’t move. I can’t disturb Toby.” In the ’70s in Munich, we had a nice garden. Toby was hunting all night and bringing back mice. But during the day, when another dog came by, Traktor was allowed to chase Toby up the tree and bark. When the dog was gone, Toby came down as if nothing had happened. That was the deal, and they played that game whenever other dogs came by. One day I had to give up Toby because my sinusitis wouldn’t stop. Now where we live in the country, it’s an ideal arrangement because we have cats and dogs again. Our neighbor’s beautiful dog Beppo thinks he’s ours when we’re there. And there are two cats as well.

Did you grow up with pets?

Yes, Irish setters, several generations. I was responsible for them. My parents never had cats. I was the first to adopt one. I have to tell you the story of how Toby came to us, me and my then girlfriend. We were living in an apartment in Munich in the late 1960s, and on Christmas Eve there was a scratching noise at the door. I opened the door: nobody there. But my girlfriend said, “Oh, you let a cat in.” The kitten just came in and we put her back outside. We weren’t in the mood for a cat. But then she reached under the door and scratched on the inside. That was so cute and she was so little. I couldn’t help it: I said, “Come on, we have to.” I left that girlfriend, but I didn’t leave Toby.

How did they get those names, Toby and Traktor?

There’s a beautiful children’s book about Toby the cat, who’s mischievous but nice. Traktor got the name from the previous owner, who didn’t want him anymore. Traktor was a wild mix, a little bit of a boxer’s face, but he didn’t have the drooping jowls. When I moved in 1978 to America, I left Traktor behind. He stayed with my then girlfriend until he got old. He’s in many of my pictures, also in the Polaroid book. He is watching over the red VW from The American Friend. He watched over that car for years.

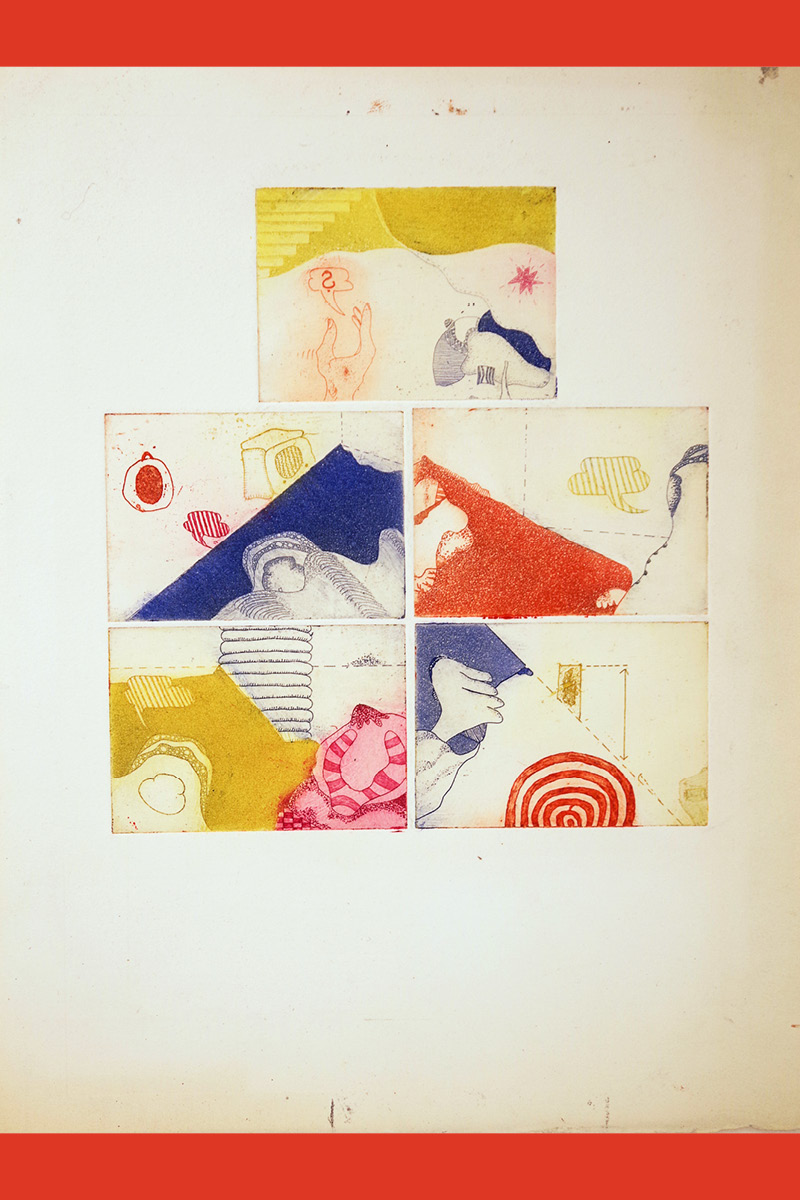

comic strips

Comic

I loved comic strips before I knew how to read. You could decipher them in another way. The first comic book I knew was Prinz Eisenherz [Prince Valiant]. And I was big on The Katzenjammer Kids. They were the best. I loved them.

There was also an important 19th-century German illustrator who Maurice Sendak told me greatly inspired him.

Wilhelm Busch. I know all his stories by heart. It’s part of my first reading. Sort of moral stories. Busch’s were the first stories I’d seen in my life drawn in single frames. They were tremendous. Much later I discovered Krazy Kat and became an avid collector of Herriman.

You have original George Herrimans?

A few old ones from newspapers.

He’s one of my heroes. Did you know that he was part Creole?

I had no idea. When I went to Paris and was rejected by the École des Beaux-Arts, I eventually found the workshop of a German-French engraver, Johnny Friedlaender. He took me on as one of his dozen or so students because of my drawings. He criticized and helped us. And I developed abstract comic strips very much based on Herriman—no figures, just shapes and forms. They were narrative in a strange way. I did them as etchings. Friedlaender thought I was onto something. So my first really independent work as a painter was a continuation of my love of comic strips. I have a handful left. Not many.

“A huge part of my general knowledge, my culture, comes from Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge.”

And Winsor McCay?

Winsor McCay is a whole different story. I discovered him and Little Nemo much later. I liked the form of comic strips, but I wasn’t so convinced they were important until the first Marvel Comics appeared in Germany as long, thin booklets. When, in Kings of the Road [1976], the character of Rüdiger Vogler goes back to the house where he lived with his mother, he finds a box of comics under the staircase. I was quoting a scene from Nick Ray’s The Lusty Men [1952], where Robert Mitchum crawls underneath the house he lived in as a kid. These tiny booklets were the way they were marketed in Germany. Disney started to publish Mickey Mouse in Germany in ’52. I invested all my pocket money in those. I had every Mickey Mouse, from the beginning. A huge part of my general knowledge, my culture, comes from Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge. I still have every volume, from number one on. Later I actually had them bound.

Huey, Dewey and Louie—

They were fantastic, and they were so beautifully drawn. I had stacks and stacks—a little frowned upon by my parents, but in the end they let it be. I was visually enriched by comics and learned to think in frames and sequences of images. Before I ever made my first movie, I learned to storyboard. My favorite frames in all those comics were the wide shots. That’s why I love Westerns so much. Later on, when films got rid of wide shots to accommodate television, I was disappointed. I also loved Carl Barks, the great original designer of the Donald Duck stories. I have a complete edition of all the stories he designed himself—very precious, one of my proudest possessions. Two meters’ worth. That’s what all my nieces and nephews and grandchildren had to go through before they were allowed to look at anything else: The Carl Barks Library.

I’m very proud that we’ve unlocked the connection between Donald Duck and your films. I don’t think that’s been made before. Of all the comic book series, I wouldn’t have guessed this one. Maybe Uncle Scrooge.

It taught me everything about capitalism and moviemaking that I needed to know.