Is Skateboarding Built for the Box Office?

By Jonathan Russell Clark

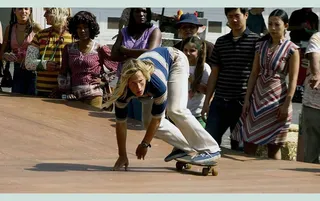

Lords of Dogtown, dir. Catherine Hardwicke, 2005

Is Skateboarding Built for the Box Office?

When a subculture goes mainstream, filmmaking tries to keep up

By Jonathan Russell Clark

May 23, 2025

Let’s begin with a clip: It’s the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and as Yuto Horigome approaches a handrail on his board, a skycam flies over on a rig spanning the width of the skate park. From this height, millions of viewers watch Horigome perform an ambitious trick known as “nollie backside 270 noseslide.” If someone had pulled off this move 20 years ago, it would have blown minds in the skate world. That’s because nobody two decades ago had ever done this maneuver on an obstacle of this size, let alone during the Olympics. A few moments later, Horigome slides off the rail and lands with such neatness, it’s easy to downplay that he just spun in the air onto the handrail and down a set of stairs. In fact, that high camera angle is a poor one. It flattens the terrain below Horigome and gives little context to his trick: We have no sense of how large and intimidating the obstacle is, no visual comparisons to show its size, no close-up to appreciate the nuanced mechanics involved. Nonetheless, the sweeping shot lends the spectacle a cinematic grandeur that is a stark contrast from the DIY, lo-fi style of skateboarding videos made by, and for, skaters. Understandably, Olympic skateboarding is directed as an event.

![]()

Yuto Horigome competing at the Tokyo Olympics, 2021

![]()

America’s Newest Sport, dir. Bruce Brown, 1962

Since its inception, skateboarding has been so entrenched in capturing itself that its history depends largely on the history of recorded skateboarding—and the sport’s progression is completely tied up with its visual output. The symbiosis between skate videos and skaters accelerates innovation. The better the tricks that are presented, the more hyped skaters are to try them. Those tricks are then refined and reconfigured, propelling the professionals to up their game—all mediated through a lens. From the scuzzy sidewalks of California in the 1960s to its 2021 inauguration as an Olympic sport in Tokyo, skateboarding has undergone significant changes in style, technique and technology, refining its imagery on screens great and small.

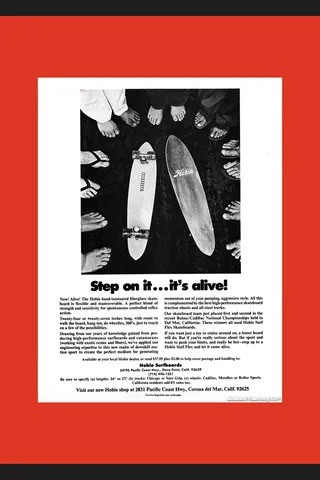

Skate cinematography as a genre is so crammed with artistry and innovation that it’s easy to forget that skate videos really started as extended ads—for boards, clothes, wheels, trucks, shoes and energy drinks. Most skate videos have been affiliated with brands, with skaters as ambassadors. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, skateboard companies such as Roller Derby and Hobie featured hand-drawn ads of children standing on thin decks with their feet close together like idiots about to slip on to their backs. Short films from the period, like Bruce Brown’s “America’s Newest Sport” (1962)—which features a surf-rock soundtrack over clips of young boys in Where’s Waldo? shirts cruising around on flat ground—functioned as infomercials, with a narrator itemizing the product’s features as skaters demonstrate them. However straightlaced the marketing was, skateboarding briefly boomed in this period, and skate parks emerged across the U.S. The introduction of contests and events in mid-’60s and early-’70s California and Florida gave skating a sense of a formalized activity akin to other youth sports. Videos from the era often highlight competition notices or non-skateboarding commentary from news reporters. It wasn’t until the 1980s that skater-owned companies and skate teams (a group of skaters sponsored by a brand) created what we now think of as the modern skate video.

![]()

Tony Hawk and Mat Hoffman performing in Taipei, 1995

![]()

1975 advertisement for Hobie

For the uninitiated, here’s how the typical skate video—generally filmed and produced by skaters and skater-run companies—unfolds: an intro overview features clips, a kind of trailer for the video that also acts as a sensibility primer. Next we see montages of individual skaters doing their best tricks. The first part might highlight a relative newcomer of great promise. Subsequent segments create stylistic dynamism, like sequencing the tracks on an album. In the past, videos would also contain what were alternately called “crash” or “slam” sections—the falls, mistakes and injuries (oof!). The finale is reserved for the best skater or best moment that ends the video on a bang. This tried-and-true format is still the template, with videos from Thrasher magazine (3.3 million subscribers) and the video platform Skate or Die (467K subscribers) now dominating the skate-tastic corners of YouTube. Just check out Epicly Later’d, a cult skate docuseries revived by Vice, whose episode on Bam Margera has drawn 5.2 million views.

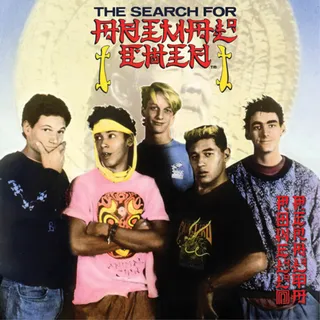

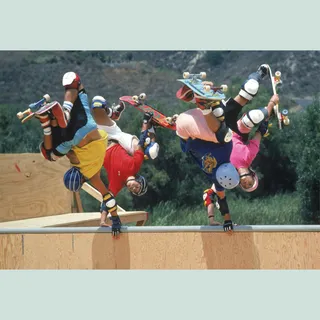

But the skate video standard didn’t emerge fully formed. In the 1980s the skate company Powell-Peralta borrowed plot, dialogue and production values from Hollywood, and director Stacy Peralta created an early and ambitious version of a proper film, complete with scripted narrative. The Search for Animal Chin (1987) follows the Powell-Peralta skate team (aka the Bones Brigade) as they seek out the legendary first skater, named Won Ton “Animal” Chin—a racist Asian caricature with the sophistication of Fu Manchu (this aspect of the movie has aged extremely poorly). But Peralta injects the rest of the hour-long feature with earnest artistry, one of the first people to take the potential of skate videos seriously. As Tony Hawk describes in his autobiography Hawk: Occupation: Skateboarder, while filming the classic finale at a custom-built half pipe, “Stacy sat in a wheelchair and was pushed around to get smooth shots; he climbed on ladders and shot from every angle possible.” You get a sense of Peralta’s point of view in the acclaimed documentary he made about this period, Dogtown and Z-Boys (2001), and the feature version titled Lords of Dogtown (2005), directed by Catherine Hardwicke. Dogtown and Z-Boys mythologizes the birth of modern skating in 1970s Los Angeles (Dogtown was the nickname for the area from the Santa Monica Pier to Venice Beach, where surf culture blossomed), when a major drought left hundreds of home pools empty and ready to be shredded. Not only does Peralta have deep nostalgia for the period, he also believes he and his crew of skaters made crucial contributions to expanding skating’s parameters in both terrain and style. Pool skating introduced new obstacles that required a new approach; its legacy of trespassing in search of spots is still in practice today. The ethos of skateboarding was born there.

For its time, the skating in Animal Chin was top-notch: the filming, editing and veneer of professionalism was a cut above product demos. High-quality film and coordinated shoots contributed to its superiority, but ultimately it’s the skating that separates it from previous efforts. Animal Chin functions like a tour video revolving around spots and montages of Peralta’s Bones Brigade. Peralta shoots the tricks so as to emphasize their difficulty and style, but we also witness the camaraderie of the team flowing from these sessions. Compare Peralta’s narrative approach to Hollywood’s treatment of skateboarding from the period in movies like Gleaming the Cube (1989), starring Christian Slater. Although you can see some fantastic skating in the latter (both Hawk and Rodney Mullen, who became professionals, appear in the film), there is not nearly enough to justify a storyline that is, frankly, overwrought and laughable.

Skateboarding suffered a major industry implosion in the U.S. in the 1980s as skate parks closed due to liability issues, and the aesthetics that emerged from that financially stagnant period reflect the economics. Without access to skate parks, devotees hit the streets. Modern street-skating was born, precipitated by misfits and oddballs who didn’t care that skating was no longer popular. Paradoxically, this is when some of the richest parts of today’s skating bloomed. The sport became truly renegade, subcultural, even illegal—hence the iconic “Skateboarding is not a crime” slogan Powell-Peralta used for its 1988 video Public Domain, which featured street-skating and a much more rugged sensibility. Shot on three film formats (video, Super 8 and 16mm), the video utilizes rigs designed specifically for shooting skateboarding, while retaining the Animal Chin–style skits and bits. Larry Clark’s feature Kids (1995), starring Chloë Sevigny and Leo Fitzpatrick, presents an extremely bleak, semi-vérité take on street-skate life in New York at this time, rife with drugs, alcohol and sexual violence—not an accurate representation of all urban skaters in the 1990s, but a suggestion of the ways that skateboarding was relegated to criminal status.

Alongside the new terrain of the streets came aesthetic parallels, including rough, fish-eye-lens close-ups from filmmakers following the action on boards themselves. With little budget and a dwindling audience, classic videos like Plan B’s Virtual Reality (1993), an hour-long cavalcade of some of history’s best skaters—Mullen, Sean Sheffey, Pat Duffy, Danny Way—revolutionized skate tricks through gritty, low-quality footage of often-improvised clips. Shot from a single angle, Mullen’s innovative moves in his Jim Croce–soundtracked part weren’t planned out as elaborately as skaters would wish today (compare these to the 2024 Olympics, where Yuto Horigome’s gold-medal-clinching trick were instantly replayed from four different angles, with no aspect of the feat unscrutinized). In Virtual Reality, many of Mullen’s enders—the final tricks, and usually the best and most difficult ones—were not only filmed with just one camera, but they were shot at night with only diegetic lighting. With no stories, skits or other extraneous stuff, Virtual Reality is pure radness, start to finish.

“For all their cinematic flair, skate videos are not movies in the conventional sense.”

From left: Peggy Oki in Dogtown and Z-Boys; the Zephyr Competition Team in Dogtown and Z-Boys; John Robinson in Lords of Dogtown

Around the same time in the mid-’90s, Spike Jonze and the squad at Girl/Chocolate Skateboards introduced some lo-fi Hollywood movie magic into their projects, but with much more interesting cinematic results than Peralta had achieved with Animal Chin. Mouse (1997) alternates between skating and short sketches, but Jonze and co-director Rick Howard—who, with Jonze, Mike Carroll and Megan Baltimore, co-founded Girl skateboards and rode for the team as a pro—exude a considerably more avant-garde sensibility, particularly with the interstitial action. Jonze and Howard aren’t interested in plot or logic or thematic unity, but their vision is stronger and stranger than any skate filmmakers prior to them, as are their skills. The DIY effects and production design they employ are effective: a dude dressed as a mouse skating around to the tune of “Three Is a Magic Number” from Schoolhouse Rock!; a blaxploitation homage called “Brothas from Different Mothas” that recalls the iconic Beastie Boys video for “Sabotage,” which Jonze directed three years prior; and a memorable sequence in which Keenan Milton gets shrunk down to the size of a mouse and “tre flips” over an AA battery the size of a picnic table. These playful interludes show the creative and innovative promise of the skate world and demonstrate how its aesthetic bled into other mediums. They also tease the originality of Spike Jonze, whose cinematic vision would later crystallize in features like Being John Malkovich (1999) and the Oscar-winning Her (2013).

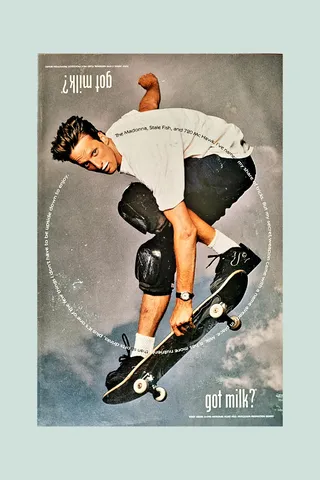

But no matter how cleverly mounted and effectively produced these segments are, the skating in the rest of Mouse remains true to the trick-first, low-angle, fish-eye-lens approach. A skate-video staple since the ’90s, the fish-eye performs three very useful functions. First, it’s essentially a lens so long that the aperture itself is visible in the frame, enabling the filmer to be able to skate close behind and simply point the camera in the approximate direction of his buddy without having to monitor the viewfinder. It also makes obstacles simply look bigger and more dumbfounding, especially from low angles. But best of all, the fish-eye absorbs so much that it makes skateboarding look believably crazy: capturing the takeoff spot, the obstacle, the landing and the roll-away—all while keeping the skater in frame. The fish-eye has also proven just as vital for still shots of skateboarding, something that non-skate photographers rarely grasp (think of Hawk politely informing Annie Leibovitz that she was shooting the wrong moment of his trick for a “Got Milk?” ad in the 1990s).

![]()

Tony Hawk in a “Got Milk?” ad shot by Annie Leibovitz, 1998

![]()

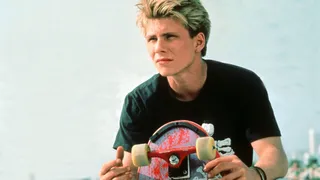

Tony Hawk at home, 1987

Hawk, ironically, could have used his own advice when Birdhouse, the company he founded and rode for, released The End (2000), a skate video in the tradition of his mentor Stacy Peralta. A big production with a budget for special effects and a soundtrack that licensed “Under Pressure” by Queen and David Bowie, The End played in theaters and hoped to be a crossover hit. It was not. Director Jamie Mosberg shot much of the skating with similar tactics as other skate videos, but too many of the best moments are sullied by inexplicable choices that violate the pragmatic, “form follows function” ethos of skate cinema. In the video’s most inspired part, Heath Kirchart and Jeremy Klein don black suits and ride around at night with a giant ramp that they launch off of to grind business signs, bus stops and other pieces of urban architecture. The stuff they do is instantly iconic—dangerous and impressive. But Mosberg shows some of the best tricks from puzzlingly distant POVs, or intercuts alternate angles as a trick occurs. When I first saw it, these moments seemed inexplicable to me until I realized what The End was trying to accomplish: Like the cinematic techniques used in the 2024 Olympics, it seems to want to usher skateboarding into a more “broadcast” or even Hollywood format—or, to be more generous, to elevate skaters by depicting them the same way movies and TV depict their heroes. Hawk’s stated objective was to “make a movie that raised skate video standards.” While I believe The End to be a superlative skate video, it’s ultimately an unrepeatable feat—most skate brands can’t or are unwilling to afford that level of budget or professional crew.

For all their cinematic flair, skate videos are not movies in the conventional sense. Most films about skateboarding are genuinely bad. Even when they’re competently made, they rarely capture the authentic vibes of the sport. Early Hollywood efforts like The Skateboard Kid (1993) simply inserted skating into genre molds. The Skateboard Kid is a children’s movie about a magical talking skateboard voiced by Dom DeLuise (for real). Gleaming the Cube is a crime thriller involving a conspiracy to send weapons to Vietnam. These movies simply use the sport as a plot device in stories that contribute nothing to the culture. Thrashin’ (1986) thrusts its protagonist (played by a young Josh Brolin, looking more jock than skater) into rival punk gang wars. Street Dreams (2009), a narrative feature starring pro skater Paul Rodriguez and co-written and co-starring Rob Dyrdek, founder of Street League Skateboarding (an international tournament series), attempts the skater’s point of view: The protagonist dreams of landing a trick he nicknames the NAC (“Not a Chance”). Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park (2007) revolves around a gruesome accident on a freight train in Portland, Oregon. Though the details of the teenaged protagonist’s skate life feel authentic, the skating sequences—such as one that takes place at Burnside, an iconic DIY skate park under a bridge—are more atmospheric than virtuosic, moody montages in which the darkness of the characters’ lives is momentarily relieved. Jonah Hill’s directorial debut, Mid90s (2018), is an appealing coming-of-age story, but the skate sessions themselves seem like a poor facsimile of the real-life action.

“Skateboarding is inherently improvisatory and virtuosic, an activity where there is no meaningful distinction between practice and performance.”

From left: Kids, dir. Larry Clark, 1995; Gleaming the Cube, dir. Graeme Clifford, 1989; Mike Carroll, Rick Howard, Megan Baltimore and Spike Jonze of Girl

Skateboarding is an arduous education in muscle memory and pain tolerance, elaborate footwork, graceful balance and bone-crunching danger. It’s heroic, and movies love heroes. So it was natural, maybe even inevitable, that skate filmmaking would evolve from DIY hobby to mainstream cinema, even if some of the authenticity of skate culture is lost in the conversion. But the cinematic coverage of skating during the 2024 Paris Olympics, with its costly technology, high-tech gear and millions of worldwide viewers, is even further afield from skateboarding’s original spirit. It’s not the competition that’s antithetical—contests have always been a part of skate culture; it’s the stage. Imagining Tony Alva from the 1970s or Christian Hosoi from the ’80s or Chris Senn from the ’90s entering the consistency-obsessed, athletically optimized world of the Olympics is a little like imagining Bob Dylan singing karaoke: It focuses entirely on the wrong talents. Skateboarding is inherently improvisatory and virtuosic, an activity where there is no meaningful distinction between practice and performance. The camaraderie, iconoclasm and kookiness that make skateboarding irreplaceable to its devotees—the rebel spirit that filmmakers and skate brands have been trying to represent for decades—are lost in the Olympic forum. The best we can hope for is that those who discover skateboarding through the Olympics will explore beyond the glossy veneer to the bumpy, streetwise legacy captured in videos made by and for skaters: They speak for themselves.

From left: The Search for Animal Chin, dir. Stacy Peralta, 1987; 1978 advertisement for Hobie; still from The Search for Animal Chin

_2048x0.webp)

_2048x0.webp)