Ezra Edelman: Olympic States

By Caroline McCloskey

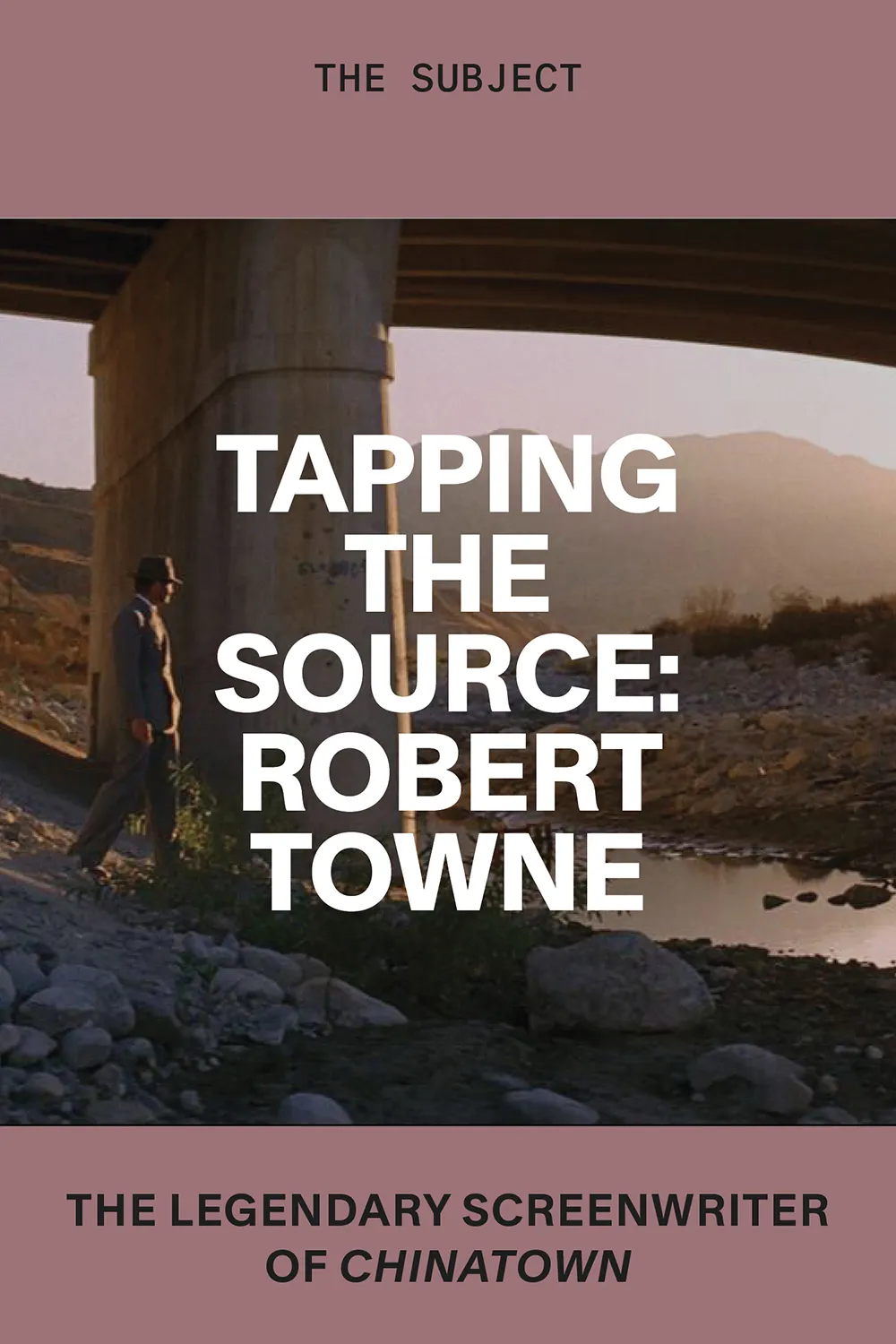

Without Limits, dir. Robert Towne, 1998

Ezra Edelman: Olympic States

By Caroline McCloskey

The director and sports fanatic highlights a biopic, a documentary and a narrative feature—all made by Oscar-winning filmmakers—that create a prismatic portrait of the 1972 Munich Olympic Games

August 1, 2024

![]()

Munich, dir. Steven Spielberg, 2005

![]()

Donald Sutherland as Bill Bowerman in Without Limits

Within his circle of friends, O.J.: Made in America filmmaker Ezra Edelman is known as a committed sports obsessive, a fan so promiscuous in his love of competition that you’re as likely to find him courtside at Wimbledon as you are to see him in the stands of an Arsenal match or on the parquet at the WNBA All-Star Game. Growing up in Washington, DC, the youngest of three brothers, Edelman was a talented athlete who turned to sports for both refuge and structure, but even as he moved to New York and began working at Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel in the early aughts it was unclear how he might use this passion in service of a greater good. The son of activists, he knew he would have to pick up the family mantle one way or another.

The world of professional athletics, it turns out, has plenty of its own political connections. In his filmmaking, Edelman applies dogged journalistic inquiry to big existential questions about identity, agency and justice. His early work analyzed the racial and commercial interests behind the Magic Johnson–Larry Bird rivalry as well as MLB pitcher Curt Flood’s groundbreaking antitrust dispute before reaching new heights of ambition with O.J.: Made in America. The nearly eight-hour exploration of the primordial stew of talent, celebrity, race, ambition and economics that begat one of America’s most notorious figures won the 2017 Oscar for Best Documentary Feature.

In anticipation of the Games in Paris, we asked Edelman about his favorite Olympics movies. Without hesitation, he suggested a compelling triple bill: Robert Towne’s Without Limits (1998), Kevin Macdonald’s One Day in September (1999) and Steven Spielberg’s Munich (2005). Each of these films in its own way orbits the catastrophic events of the 1972 Olympics in Munich, where 11 members of the Israeli delegation were killed after being taken hostage by the Palestinian militant group Black September. Speaking to Galerie from his home in Brooklyn, Edelman talks through the three films’ thematic adjacencies, discussing how the Olympic Games have changed in the half-century since Munich, his own history of hardcore fandom and the value of sport during crisis.

“I don’t think competition, pure competition, is ever frivolous.”

When we first talked about Olympics movies and I asked what came to mind, you immediately identified this trio of films.

It happened organically, in the sense that I thought of Without Limits just because of Steve Prefontaine in the ’72 Olympics. I had recently watched it again, and it’s one of my favorite sports movies. It happens to align naturally with One Day in September, which is one of my favorite documentaries and really was a point of inspiration for me in terms of doing what I do, as far as the fusing of sport and politics in a much deeper way. When you’re talking about Olympic films, I wouldn’t have thought about Munich, but it feels like an interesting triptych: two features, one documentary, all different ways of dissecting politics in the realm of sport.

They touch on different political edges.

Even Without Limits, which focuses on Steve Prefontaine as an athlete, has politics within it, about professionalism and amateurism and the lack of control that amateur athletes had at that time. In many ways, that has changed completely in the 52 years since that movie took place. Thankfully, now athletes can earn a living plying their trade without forfeiting their Olympic eligibility. So it’s a good continuum: Without Limits is pure sport, One Day in September is a mixture of sport and politics, and Munich is all politics. Munich is still a dissection of the events, but it’s done through the perspective of the Israeli politicians and Golda Meir, who sends her people to get retribution [for the killing of Israeli athletes and coaches at the Munich Olympics].

Given the order in which I saw them, to me it felt like a progression. Without Limits is the dramatized account of one individual—the hostage crisis at Munich affects Prefontaine’s (Billy Crudup) story, but it’s not the center of the frame. Then we go into the documentary, which is a granular, head-on look at the actual siege. And finally, with Munich, we get into the aftermath of those events.

That is the correct order in which to watch them. It speaks to the import of what happened—how historically and culturally significant it was—that there was the need to dramatize it at all in Without Limits, a movie that ostensibly has nothing to do with those events.

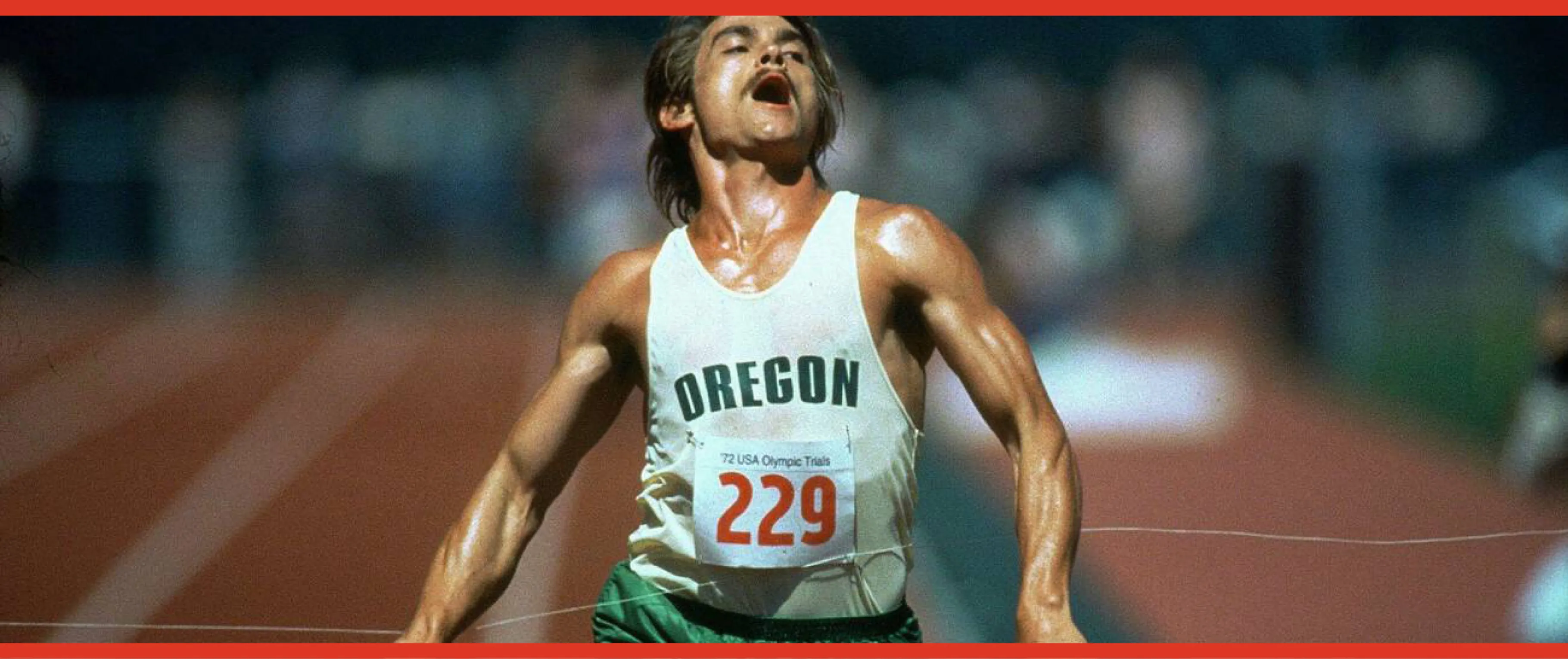

The Olympics are meant to be the culmination of Prefontaine’s achievement, but they become a thwarted dream.

For Prefontaine, the Olympics reveal the limits of his own powers. He has so much self-belief and charisma that, watching it, you’d be hard-pressed to believe he wasn’t going to win. At the Olympics he runs up against the fact that he ran as hard as he could, he ran a great race, he couldn’t have done better, and he still finished fourth. So the story is about what happens when you come up against challenging your own self-image. Everything that you oriented your brain around didn’t come to fruition at the most important moment in your life.

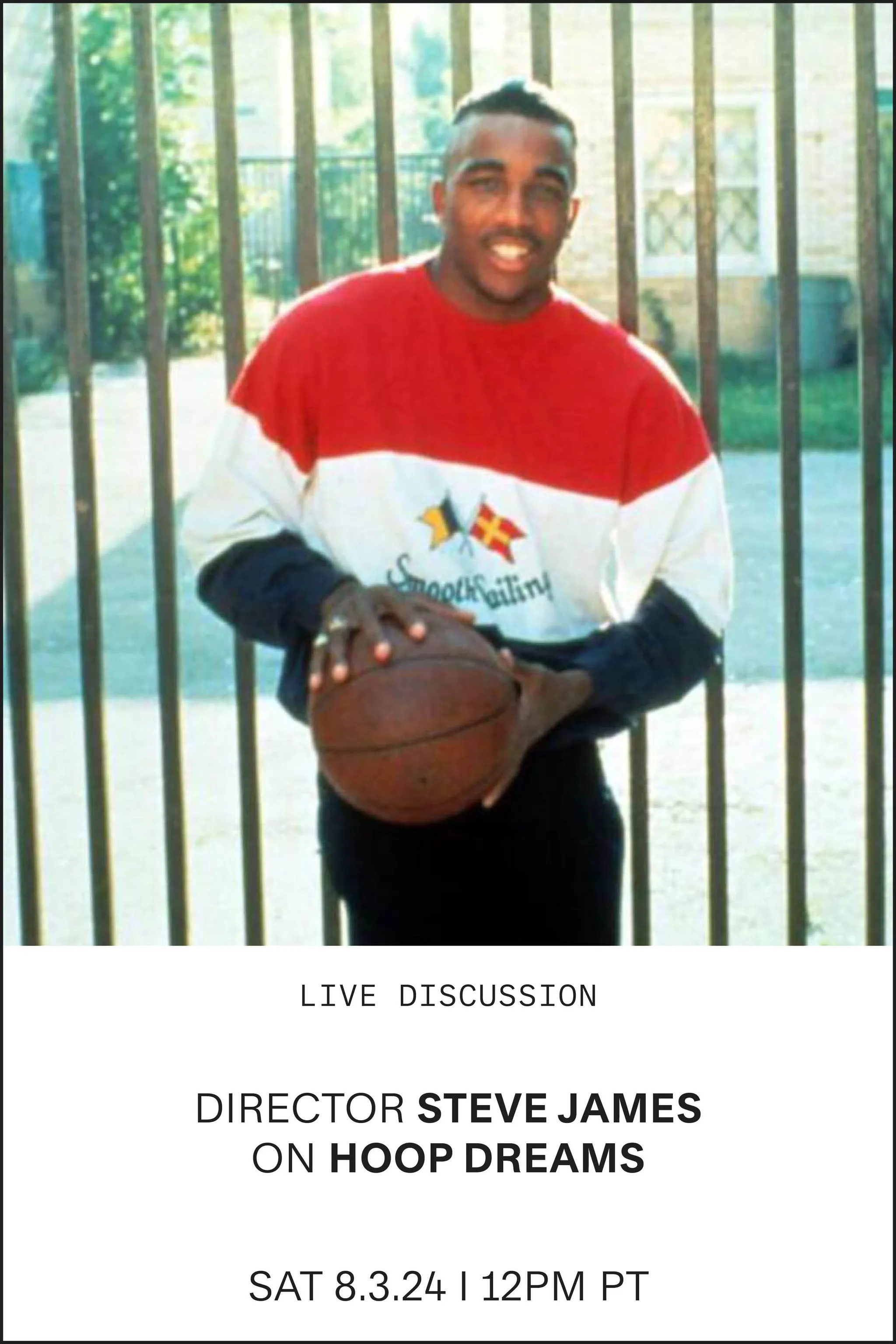

One Day in September, dir. Kevin Macdonald, 1999

Failing to medal is in some way the real test, because he’s never lost before. What happens when his self-belief is challenged?

It shattered. And, in a way, another journey started. After the Olympics he finally gets over himself. He’s ready to start—hence the tragedy of his death. Would he have been a changed person? Who knows. Getting back to this idea of the topic of amateurism in that movie, it’s just like, you’re in college and you can go balls to the wall training for the Olympics. What happens when you’re no longer a college student and you’re working at a bar as a bartender in Coos Bay? Are you supposed to live in poverty to pursue your Olympic dream? There is such a purity of purpose, but you’re sacrificing everything for what—what does a gold medal represent? Obviously it’s the ultimate embodiment of success, but what does that thing do for one’s sense of self? And conversely, when you put your whole life into this one thing and it doesn’t happen, what does that do? In the case of Pre, I imagine that you would’ve run in the ’76 Olympics and maybe you would’ve won.

It’s a crazy irony when not medaling at the Olympics overshadows the feat of even getting there in the first place.

Making the Olympics is an amazing accomplishment. A Herculean achievement. The pool’s very small. To make the American Olympic team in any sport, but especially in track and field, you have to be the elite of the elite. I was watching the 100-meter heats of the Olympic track-and-field trials a month ago and thinking that a third of those athletes, 16 of those runners, who clearly are the fastest people in America, aren’t even going to make the final race. It’s crazy what one puts himself or herself through just to get a shot and then lose in a prelim.

I want to talk about Pre’s coach Bill Bowerman’s (Donald Sutherland) speech at the Olympics, which addresses the symbolic value of the Games as a peaceful meeting in which people put down their weapons and compete. He says, “There’s more honor in outrunning a man than in killing him.” What are your thoughts about the value of sport in moments of unrest?

As someone who has thought a lot about the “frivolity” of sports and what they give us, and how much time I’ve spent watching them and being obsessed by them and absorbed by them and wondering what the point of it all is, I have to argue that there is purpose. I don’t think competition, pure competition, is ever frivolous. I think it’s life-affirming.

Can you elaborate?

When we think about political division or, even worse, countries that are at war, the idea that athletes can come together in the spirit of healthy competition and want to win for the purity of sport is a concept as old as time, going back to the ancient Olympics. It really is an important thing because, if you break it down, what do you learn from sports in terms of teamwork and competition? What are the values that are built by going through a process of practice and training and pushing yourself and taking direction? I’m going to sound like the most Pollyannish person, but sport is unifying. There’s this common thing that we have in America, which is so fraught with division, that when we’re watching the Olympics we’re all rooting for the same people. We have a collective desire to see an American win. We all are invested in these stories, Black or white, rich or poor, gay or straight, wherever they come from—and that’s real. Wherever we can find common ground, that’s real. Why does sport, why does culture in general—movies, music—why do they hold places of importance? It’s because of what they provide for us as humans, both internally and how they connect us with a greater community of people. The irony is that I’m saying all of this, but I’m not somebody who likes to watch sports with people. I like to sit on my couch and watch a game by myself. I don’t want to experience it with other humans. I want that deliverance all to myself.

Really?

The only sport I like watching with people is soccer. There’s an energy that goes into the movement, the buildup, the almost orgasmic release when a goal is scored. That’s something that can’t be replicated without people. I’m sure that’s why a lot of people watch games together. That’s also why it’s fun to go to a game. It’s the same idea of getting that rush and the fulfillment that comes with that, the energy of it. But drunk people in a bar, no thank you.

Your work often uses sports as a vehicle for telling stories about politics, about social realities—

I would say about the world.

About the world, exactly. So bringing it back to One Day in September, you mentioned how that film informed your own work. Can you tell me about that?

As a kid I was obsessed with sports. I’m the youngest and I liked to, and still like to, play sports. I liked to watch sports. It gave me meaning, it gave me order and it was a passion—maybe also to the point of distracting me from anything that was traumatic in life. Sports were a place where you didn’t have to deal with life’s problems. I always had a game I could watch, I always had a team I could follow. So it was both great and probably limiting at the same time, but it’s always been there, this steady companion. So it’s like, How do I turn this into a career? At the same time, I understood that sports can seem frivolous. Ours is a world that is deeply fraught, deeply fucked-up, and I felt that because of the political household in which I grew up, I had some obligation to address that world in some way.

So the question becomes, How do you combine the two?

I’d never had a desire to be a sports writer. How can I tell stories in this realm that touch on the greater world we live in? Be it race, class, economics, celebrity, fame. So I think that’s always been my focus of trying to legitimize myself in the world, and maybe in the eyes of my parents. Traditionally the sports section is the toy department. How do you work in the toy department but still do meaningful work that touches on our humanity in our world?

And One Day in September illuminated a path for that.

When I saw One Day in September, I was working at Real Sports at HBO, which ostensibly was the one vehicle through which to do this in that time. I started working there around the time One Day in September came out—I think it won an Oscar in 2000. So before I even had my own cognizant ambition of making longform documentaries, I saw this thing that was like, Oh, I want to do that. I want to tell a bigger story—about sports, but about politics in the world. It’s a film that’s about the Olympics, but it’s really about those families and the victims. It’s done with real depth and sobriety, but it also has the rock and roll element to it, based on the music cues. There’s a hipness to it that elevates it beyond a certain treatment that might be, considering the material, potentially clinical. Kevin Macdonald did it in a way that was entertaining and thoughtful and emotional. It was tangible to me.

“I think that the spirit of competition was different, and in some ways better, when it was pure.”

He also had an unusual degree of access. Along with the families of the victims, Macdonald was somehow able to track down and talk to the last surviving Black September member from the siege.

I was just always so impressed that he found one of the terrorists. I was like, “How the fuck did you do something that the Mossad couldn’t do?” I interviewed him after he made Touching the Void and asked him about it. We were in the elevator in a hotel in London, and I said, “I just have this one question for you: How the fuck?” And he was talking about how there was literally a “Show up here” type of spy game in terms of how you could actually get in contact with somebody and whether it’s going to happen and the lack of control you have to get to that point. That was always one thing that stuck with me in terms of being really impressed with the film. Tracking down and interviewing one of the terrorists made it journalistically significant, beyond the emotional component of having the families of the victims. You have both sides. And so then, from that, it’s like, well, Munich is that, it’s just a different treatment. One Day in September was analyzing an event: There were terrorists who took Olympic Israeli athletes and coaches hostage at the Olympics and murdered them. That was the act it was dissecting. That leads into the third movie, which offers a little bit more of the perspective of why: Who were these people?

Munich takes a nuanced look at the moral repercussions of engagement and retaliation.

It’s part of Spielberg’s political Jewish oeuvre. And it’s the first time Tony Kushner worked with Spielberg, if I’m not mistaken. So you have the weight of the most magical Hollywood storyteller taking on this subject that is deep, philosophical, political and very sober.

What stands out to you about Munich?

The night where they’re all staying in the safe house. And [the Israeli operative played by Eric Bana] ends up in the conversation on the stairwell with his Palestinian counterpart about the conflict. You have two people, speaking from their perspectives, and then you realize that they’re husbands and fathers, that we’re all more the same than we are different. But it also, needless to say, speaks to where we are in the world now—even more so over the past year, with what has happened with the war in Gaza. Except that we are no longer able to have that conversation.

From left: Eric Bana and Geoffrey Rush in Munich; Billy Crudup in Without Limits

Can you connect the dots on these films vis-à-vis the Olympics?

The quest for winning an Olympic medal, as embodied by Steve Prefontaine, is really about testing the limits of our body and our mind and of our human stuff. When you think about what those movies are dissecting, specifically the murder of those Israeli athletes at the ’72 Games, those athletes didn’t get that opportunity. But at the same time, Palestinians have been living in an apartheid state for decades, dehumanization that has prevented them from being able to pursue the same dream of testing the bounds of their best selves. Palestinian athletes couldn't compete for their country in the Olympics before 1996. Those who get to compete for the Olympics are then these special few, when you think about how many people don’t have that luxury.

Statehood is a prerequisite for participation.

That’s exactly right. There will be very few Palestinian athletes at the Olympics in Paris.

These films depict the events of a half-century ago. So what has changed? We’re not going to untangle the Gordian knot of the Israel-Palestine conflict, but how have the Olympics changed since 1972?

I think that the spirit of competition was different, and in some ways better, when it was pure. When our worlds were farther apart, these cultures meeting face-to-face in reality was this special event. That doesn’t exist anymore. There’s no longer the concept of amateurs. Many of the best athletes are already rich, famous stars. Even professional athletes get to compete in the Olympics. The specialness of pure amateur competition no longer exists. It’s a smaller world.

More globalized.

It’s globalized. So the concept of meeting new cultures doesn’t feel the same as it used to. Now it’s all about the commercial dollar. The corruption of the IOC [International Olympic Committee], that’s been very clear. That’s been going on for years and years, how all these officials have lined their pockets in terms of why the Olympics end up in which city. The whole system is a joke and it’s broken. But the purity of the competition itself still exists.