Tapping the Source: Robert Towne

By Chiara Barzini

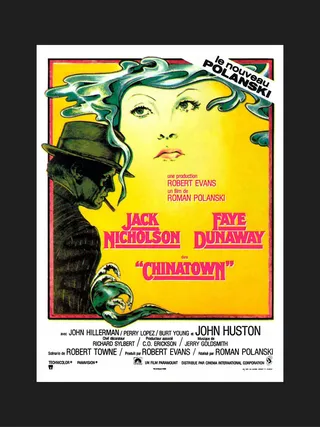

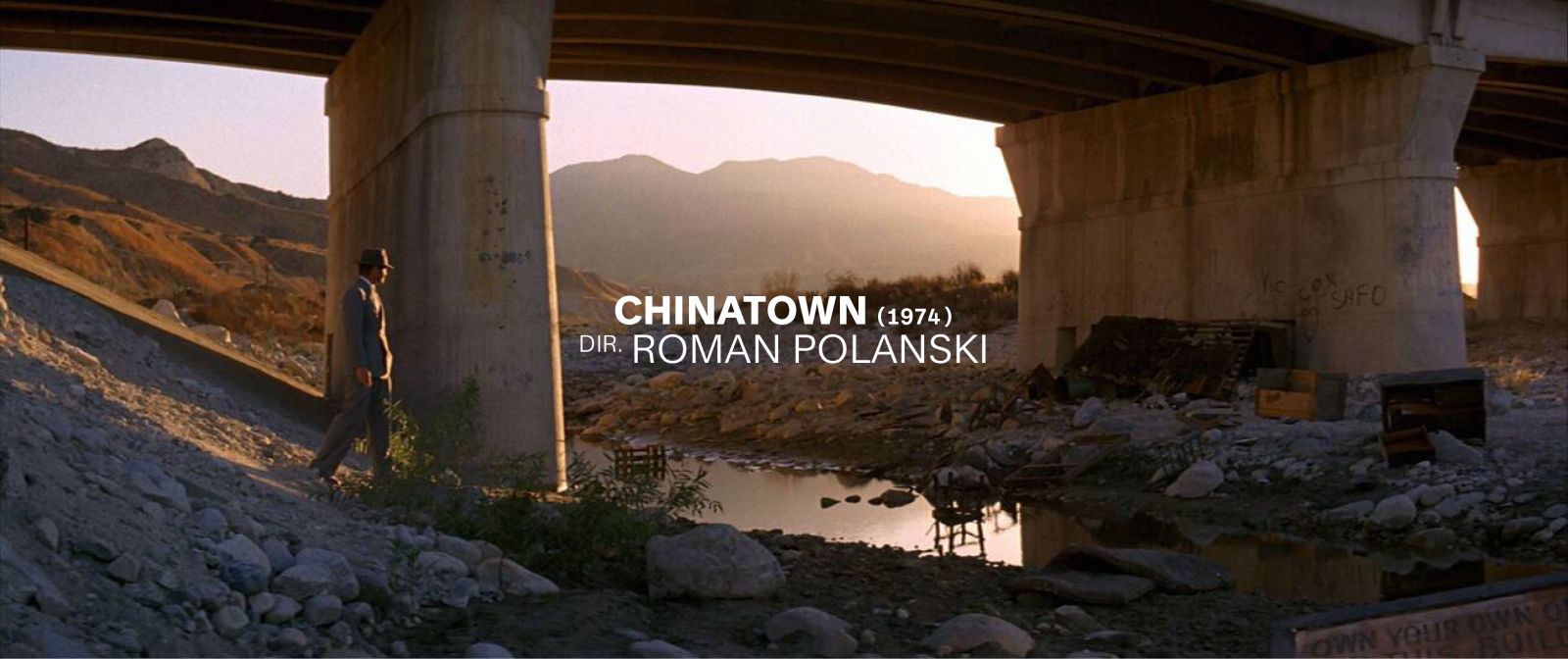

Chinatown, dir. Roman Polanski, 1974

Tapping the Source: Robert Towne

Chiara Barzini

Talking Los Angeles water and power with the legendary screenwriter of Chinatown

June 10, 2024

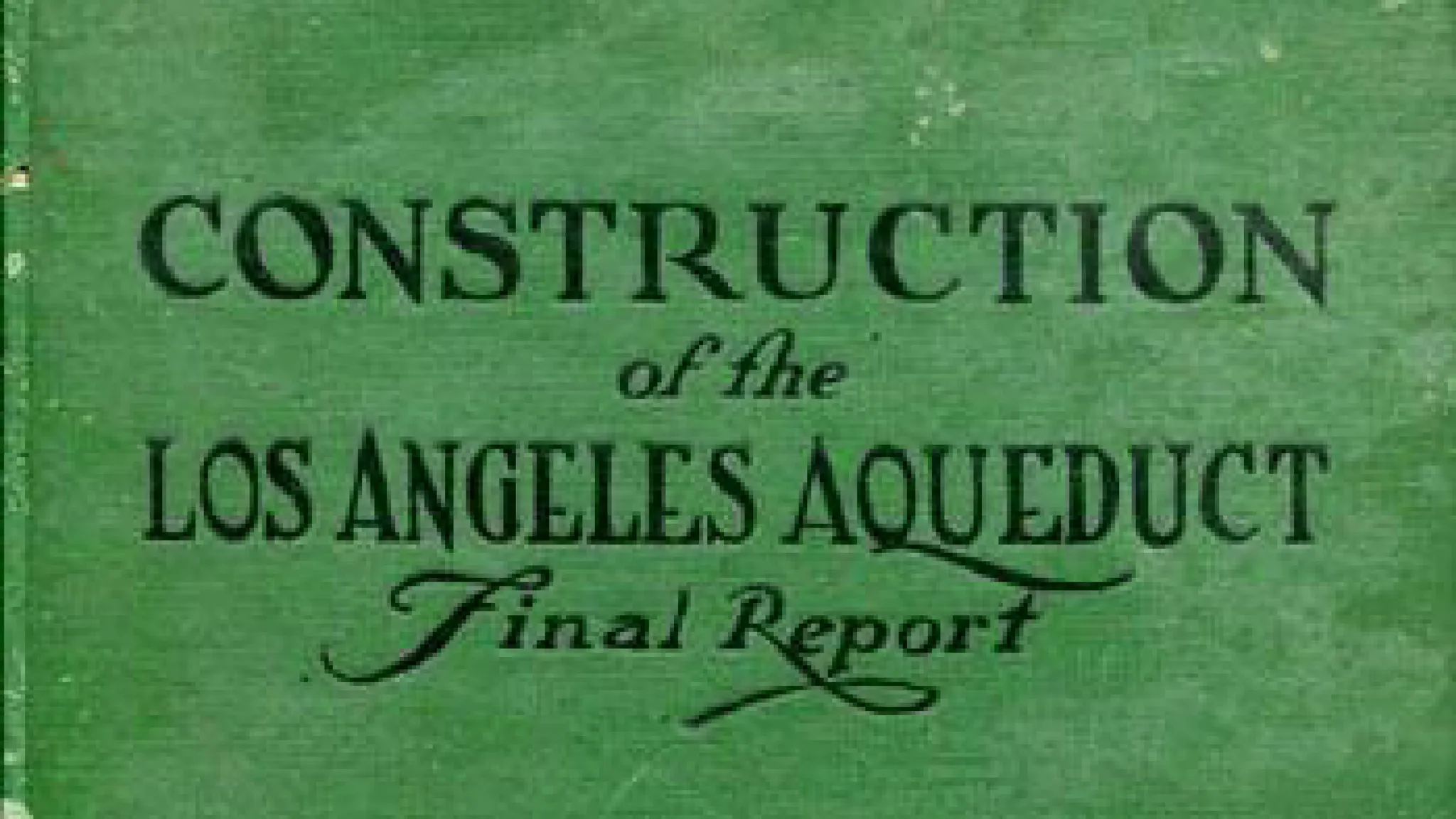

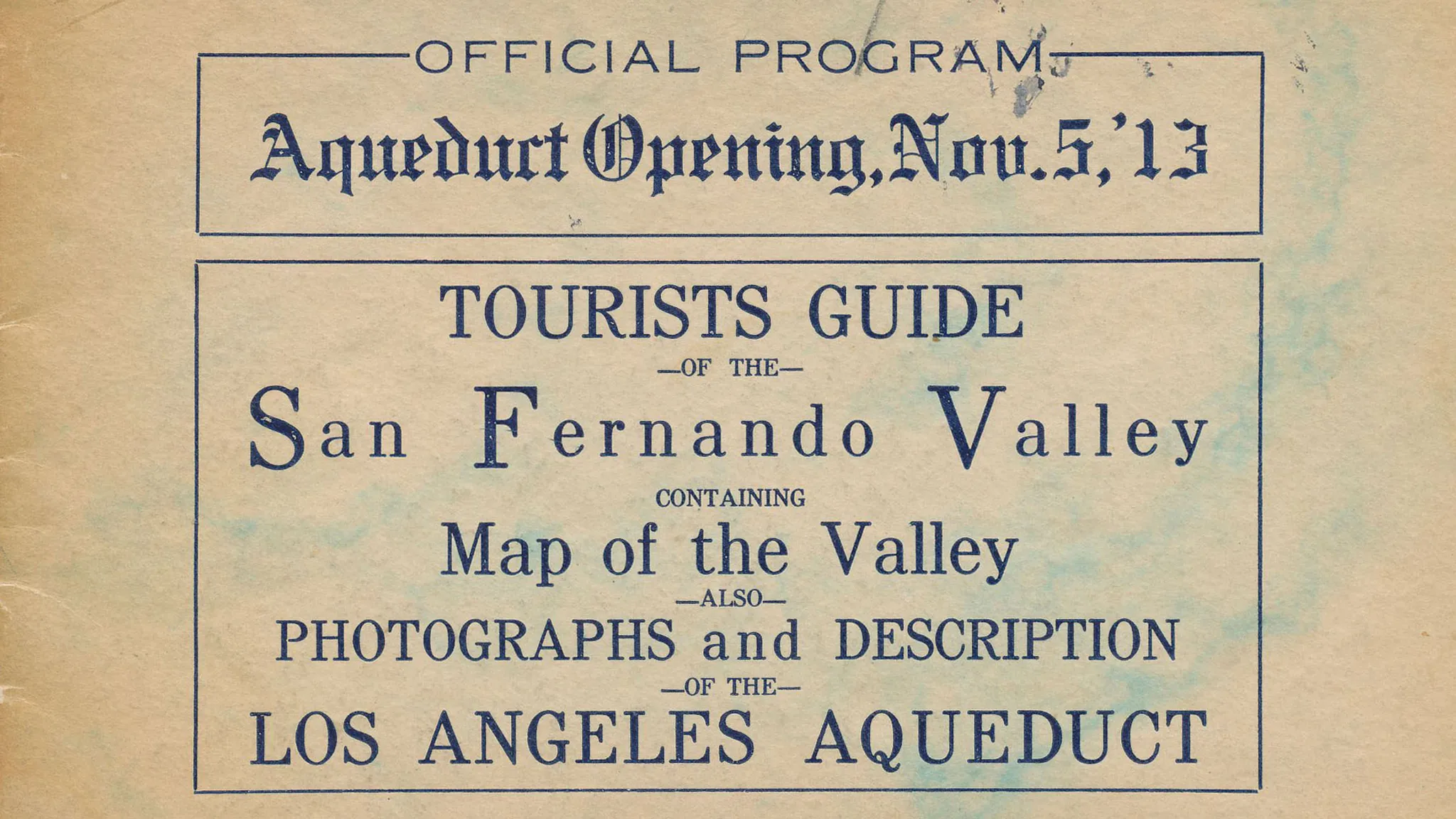

In 2017 a friend gifted me an original construction manual for the building of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, published by the Board of Public Service Commissioners of the City of Los Angeles in 1916. The scandalous 338-mile engineering masterwork had allowed chief engineer and builder William Mulholland to surreptitiously steal water from the Owens Valley to bring it to Los Angeles, the same scheme that had inspired Roman Polanski’s 1974 neo-noir masterpiece Chinatown. The first page of the manual was signed by William Mulholland himself, like an autographed copy of a novel by a famous author. I don’t know why, but I think you need to have this.

![]()

Robert Towne in 2006

![]()

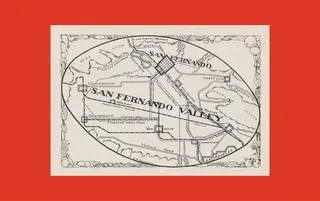

Map of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in the San Fernando Valley circa 1913

I did need to have it. I was traveling across California when I received the book, and when I returned home to Rome, amid the city’s own colossal watercourses, the manual began to speak to me. Inside were original photographs. Silver prints and detailed maps of water basins, dams and canals were folded into a special pocket on the last page. It was not so much a book as it was a private dossier. It looked alive. The most powerful thing about it was all the infinite geological and meteorological details you could perceive under the yellowing documents. The landscapes, curves and intersecting lines on Mulholland’s diagrams spoke of barren topography and empty spaces. They revealed a relationship between the concrete and nothingness. Creating dams in a dry desert canyon had the surreal quality of preparing a baby’s room and filling it with toys before the baby was even conceived. Channels would be built to contain a water that didn’t yet exist, a water that would soon run across torrid desert plains and create an improbable Garden of Eden, an orange grove to quench the thirst of millions of Americans. Polanski’s Chinatown is a film that belongs to those maps. It sits exactly in the interim space between a dreamed-up city and its blood-thirsty (and water-thirsty) construction. It presents a place on the brink of becoming what Orson Welles called “a bright and guilty place.”

My father had shown us Chinatown before we moved from Italy to the San Fernando Valley in the early ’90s. In the backyard of our new ranch-style Van Nuys home, he juiced the lemons from the garden and gazed at the sinister crows croaking as they perched on the electric cables. “This used to be paradise,” he sighed. I was interested in that interim space, so in 2021 I embarked on a trip to follow that crumpled aqueduct map and decided to write a book about it.

Before setting out on the trip, I had dinner with the New Journalism pioneer Gay Talese in New York. He suggested that I reach out to one of the very few people in the world who could still deeply talk about the making of Chinatown. “If there’s anyone you should speak to about water, it’s Bob Towne. He wrote the damn thing. I can’t believe you’re not going to see him right away,” Talese said so matter-of-factly that it left no space for questions. Reaching the legendary screenwriter Robert Towne seemed an impossible feat. Every time I had previously tried, I reached a dead end. I knew he was reclusive and hadn’t allowed interviews in recent years. Nevertheless, when I arrived in Los Angeles, I called the number that Talese had given me. An answering machine from another era picked up. I left a message and never heard back. I took off with my old map around California and forgot about the phone call.

On my last day before returning to Italy, my phone rang while I was at the counter of a department store. There was a quiet, distant voice on the other side: “Chiara?” “Yes?” There was silence for a moment, then the voice continued. “It’s Robert Towne here. I got your message.” I frantically parked my cart by the exit and ran out to the parking lot. “Robert!” I screamed. “I have a daughter who shares your name,” he replied, “so I thought I should call you back.”

I drove home, packed my suitcase and dashed over to his storybook-style 1930 house, aptly perched on top of a magical hill in Silver Lake, not far from the location of one of Chinatown’s most iconic scenes, the one where Jake is in a rowboat and pretends to photograph his associate while actually snapping photos of a questionable rendezvous between Hollis and Katherine. I was greeted by Bob’s wife, Luisa, and their daughter, Chiara. They were both exceedingly warm, though a bit surprised to see me. It was rare that anyone showed up for interviews in those days, even rarer that Bob agreed.

Bob sat on a cream-colored, paisley-patterned couch in the living room like a wise oracle. Behind him reigned a large framed poster for Chinatown. He was smiling, his bright attentive eyes sparkled. At 88 he still looked radiant, exuding intelligence and curiosity. He had long, pulled-back frizzy white hair, rock-star looks intact. It was almost Christmas, and the city outside the window brimmed with the eerie frenzy of trying to make sense of a winter holiday under the usual scorching sun. Decorated palm trees blew in the wind, trying to pass for modified fir trees. Luisa took off to buy food for the holiday dinner. Chiara, Bob and I stayed on the couch.

Robert Towne had written two of my favorite films about Los Angeles, Chinatown and the 1975 comedy Shampoo. Chinatown won him the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, and both the film and script are still being taught in practically every film school in America. Bob’s initial interest in Los Angeles’s water had its roots in nostalgia. In 1971 he came across a copy of Carey McWilliams’s Southern California: An Island on the Land, a 1946 Southern California bible telling the whole (dark) story of the city’s missions, migratory movements, film industry and unlikely preachers. Bob had particularly fallen in love with a chapter titled “Water! Water! Water!” Something about McWilliams’s voice had lured him in. In a 1994 essay on Chinatown, Bob wrote: “Along with Chandler he made me feel that he’d not only walked down the same streets and into the same arroyo—he smelled the eucalyptus, heard the humming of high tension wires, saw the same bleeding Madras landscapes—and so a sense of déjà vu was underlined by a sense of jamais vu: No writers had ever spoken as strongly to me about my home.” Now he was eager to show me the original edition of the book that set everything off. “Chiara, you know where it is, don’t you, sweetheart?” he said to his daughter, who smiled and jumped up. She knew where everything was. There was so much tenderness and affection between them it made me want to cry. Chiara disappeared into Robert’s office. She returned with the book and started leafing through it. “It says Public Library, Eugene, Oregon,” she remarked. “The last person checked it out on the 21st of April 1970, the first was in ’67.” She furrowed her brows. “I feel like you definitely took this, Dad. And isn’t there a scene in Chinatown where Gittes steals records from the public office?” Bob looked up at his daughter with a bit of a rascal face. “He doesn’t steal them, honey. He borrows.”

![]()

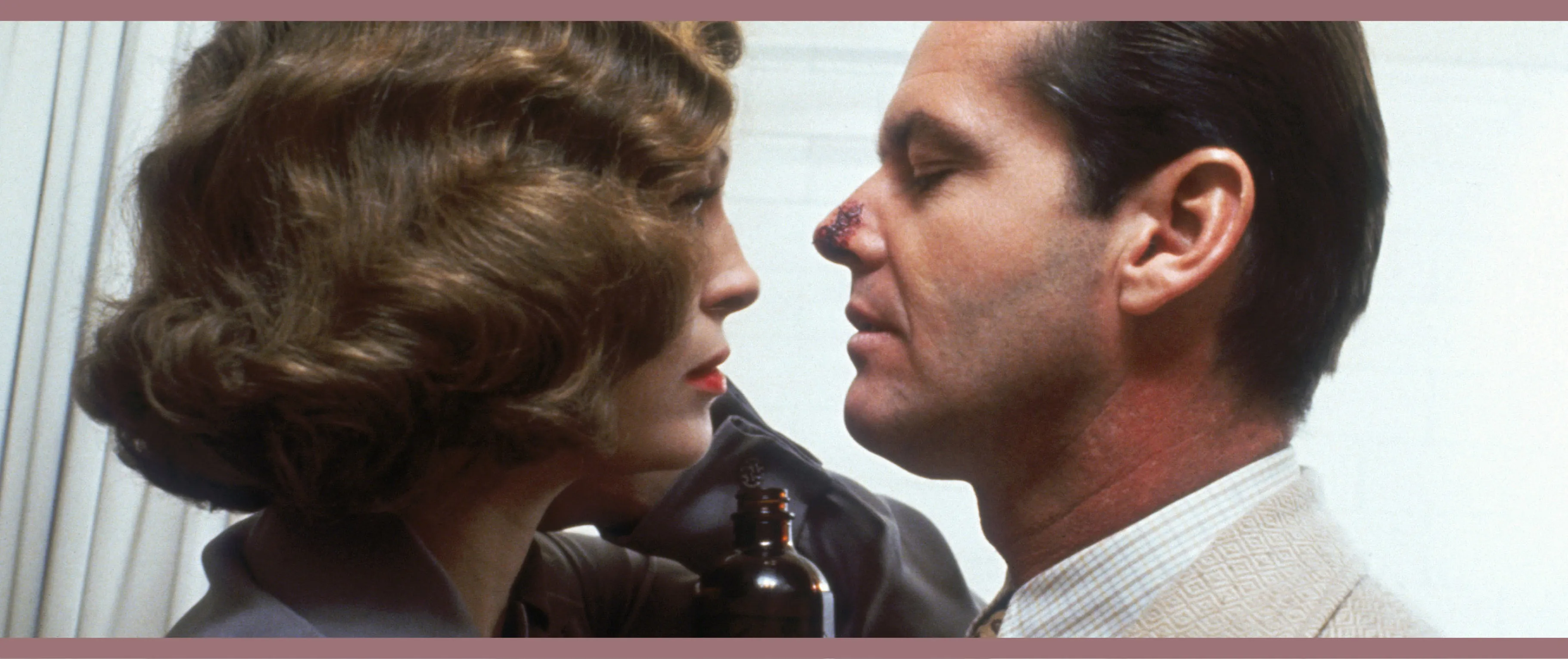

Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Mulwray in Chinatown

![]()

a 1974 French poster for Chinatown

After discovering McWilliams’s book, Robert began looking for clues of that old Los Angeles he’d been reading about. He started driving around at night, when he felt the real soul of the city emerged. Los Angeles reveals itself in strange and unexpected pockets, little luminous phantoms lurking in oak trees or in the cul-de-sacs of canyons. Robert searched for the story he wanted to write in Echo Park’s lake and San Pedro’s old Walker’s Cafe, places that had not changed in decades. He looked for it in the bay and, he wrote, where “the streetlamps were low and yellow and nippled and the palm trees were high with scrawny fronds like broken pinwheels.” He also visited the aqueduct and admired it. “I remember standing next to it and feeling overwhelmed by its diameter,” he told me. “The thing was huge! I thought about how much water had been stolen from the farmers. There’s no nice way to put it, but that’s what happened.”

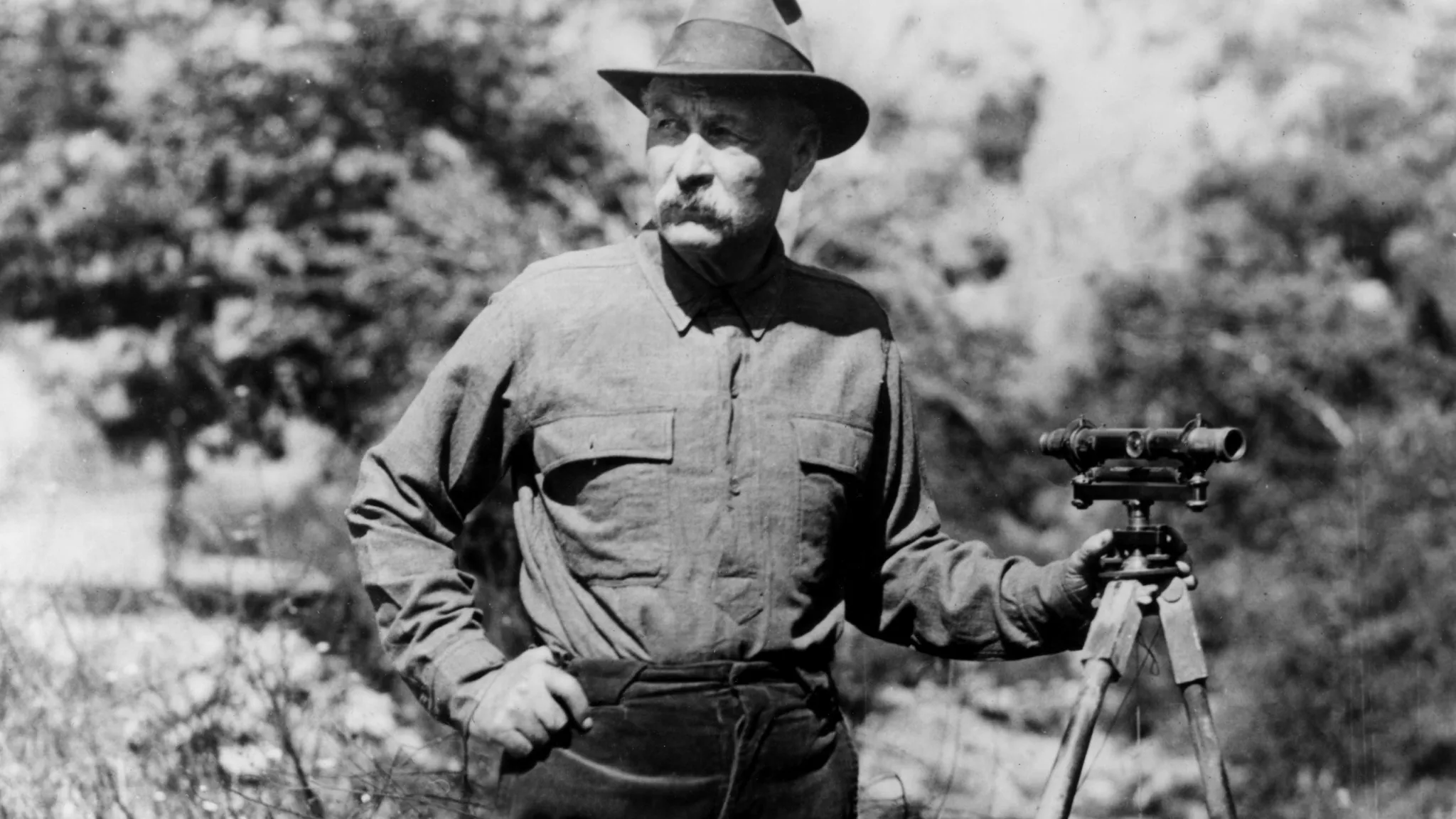

I had been fascinated by Mulholland’s ghost when I first moved to Los Angeles. His name was everywhere. It was the street that divided the Valley, where I lived, from Hollywood—the poor from the rich. It was a highway, a dam, a monumental fountain in Griffith Park, my brother’s junior high school. To know him was the key to a mysterious logic about the spirit of the city. But nobody studied the story of L.A. water in school. I had gone to high school in Woodland Hills, one of the first neighborhoods to profit from the water grab, and no teacher ever mentioned Owens Valley. Nobody knew that the last dam Mulholland built collapsed in 1928, killing hundreds of people, and was considered to be one of the 20th century’s greatest engineering disasters. Bob shared this profound curiosity: “I was fascinated by Mulholland and the way he thought,” he said. “He was a very intelligent man and completely self-taught. I don’t think it occurred to him what he was doing. When the St. Francis Dam broke, finally reality came crashing down on him.”

One of the reasons Bob started work on Chinatown in the early ’70s was that several films he’d written the scripts for were either stalled in production or revoked by the studios for being too racy. Later films like Shampoo and the 1982 sports drama Personal Best made a stir and were considered controversial, but the film he had to fight the hardest for was the 1973 Jack Nicholson comedy The Last Detail. “I’d been wanting to make it since forever, but there was too much cursing in it. I remember going with my agent to Columbia, and all the producers were trying to talk me out of it. We sat with [studio executive] David Begelman [who eventually died disgraced after being involved in a studio embezzlement scandal], and he said, ‘Bob, wouldn’t it be more interesting if instead of 40 ‘motherfuckers,’ you only had 20 in the film?’ And I remember saying, ‘David, from your point of view it might be more interesting, but from mine it’s not factual.’ I don’t think I made much headway with them, but the fact is that in the meantime, Jack had become very well known as a result of Easy Rider, and that gave us leverage with the studio, so we were able to preserve the script intact. We were in the vanguard of those trying to change the rules in Hollywood and became largely successful at it, so the movie was made. I suppose the freedom we conquered then spilled over into Chinatown and many other movies later.”

Bob fought fiercely against censorship. Stubbornness was a fundamental element in the way he forged his path as a writer. That and participating in strikes. We spoke again several times after our initial meeting, and one was at the beginning of the recent writers’ strike. When I asked him about it over Zoom, he lifted his chin with a defiant look: “I can’t even remember the number of strikes I’ve been through, but there’s a lot. One has to insist. Obstipation is necessary when you’re trying to obtain something from the studios. At the time I just said, ‘I’m sorry, it’s the way it’s going to be.’” “You opened the floodgates,” I said, laughing. He quipped, “Yeah, that’s right, that’s an apt metaphor.”

![]()

Jack Nicholson as J.J. Gittes in Chinatown

![]()

The landscape of Chinatown

In remembering the days of working on Chinatown, Bob paused dreamily to mention his dog, Hira, a huge Hungarian sheepdog who had been his travel companion, writing partner and best friend throughout the film’s production. Hira was a free animal, full of life and glee. He would chase herds of buffalos with no perception of danger. Bob had taken him to Catalina Island, off the coast of Los Angeles, where he went to work on the first draft of the script in the fall of 1972. “We got to the island on an old seaplane. The plane seated eight people, but I went over with just him.” He wrote in a decrepit lodge on the wild side of the island, between Cat Harbor and Isthmus Cove. In describing it, Bob paused and stared into space, as if trying to bring back the feeling. “The air,” he said simply. “I guess it brought me everything, it was great.” The island’s atmosphere gave him the feeling of the city as he perceived it as a child, with the same pure scents and crisp truthfulness. He wrote, “There was never a moment where some errant breeze didn’t bring me something that made me care, made me feel it was worth trying to straighten out the story, all the horrible melodramatic machinations that remove you farther from detectives and human life than any crossword puzzle.” That air that fluttered his beloved dog’s moppish white coat, as well as the mustard plants and weeds of Catalina’s wild northern shores, allowed him to envision the way things were before they were ruptured by the crime and theft of latter-day Los Angeles.

Bob invited me into his office to look at photos of his dog. Hira had been instrumental in Robert’s writing process, but also served as a kind of middle entity between Bob and Roman Polanski. “I brought him every day to our meetings. Roman didn’t like him. He got very angry when I brought him. I mean, 30 years after Chinatown, I saw Roman in France. He was being honored with something…and the first thing he brought up was the dog. It was before a large audience, and he just said: ‘That goddamned dog!’ He just went crazy about that animal, and that dog was, you know, the love of my life, really.” Hira proved good luck for the film, as Bob had gotten him from a couple of Hungarian cops who worked in Chinatown. The cops told Robert that during their training they had been instructed not to mess around with anything in Chinatown because of the language differences. “We could never tell whether we were helping prevent a crime or helping commit one,” they said. The advice they shared with him was: “Whatever happens in Chinatown, don’t mess with it,” a concept that eventually translated in the film’s last iconic line: “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.”

Robert had become friends with Roman Polanski long before Chinatown. “He was wonderful, a pain in the ass, but great. We would fight during the day and then go out on dates at night. We’d been friends since long before Sharon was murdered and all of that happened.” His eyes turned sad when he mentioned the murder. Over half a century had passed since that tragic night, but just mentioning it brought down the doom. Towne worked on the film in the shadow of the Manson murders. I’d come to believe that the city had two great stories of original sin: the water grab and the Manson murders, the moment in history when everyone began to lock the doors to their homes, the city’s definitive loss of innocence. Four days before the atrocious cult killings, Sharon Tate and Jay Sebring had been at Bob’s house for dinner. “She was such a sweet girl. Really, I loved that girl,” he said with a hard sigh. He paused, and in the dead silence of the living room, he said: “I was invited to Benedict Canyon that night, but I didn’t go.” My jaw dropped, as did his daughter’s. “I can’t believe you’re giving me this information like that!” I said. “What do you mean?” he replied. “I mean that’s a very significant detail of your life.” “He never talked about it!” Chiara said, and then we all turned quiet, trying to take it in. “No,” Bob continued with a straightforward tone. “I just didn’t go. I guess things would have been very different had I gone.” “Sure, for me too,” Chiara remarked. I hesitated to ask, but this would probably be my only chance to know. “Do you remember why you didn’t go?” “You know, it was just a group of people getting together. Sharon and Jay were the only two people I knew. It wasn’t a big gathering, so...” “Yes, but that makes it all the spookier that you were invited,” Chiara insisted. There was something about this memory that was obviously still tormenting Bob. You could detect a kind of jolt inside him, like he was trying to shake something off. I imagined he probably formulated and reformulated the answer to this question over the years without coming up with a definitive one. Polanski had asked Robert to keep his wife company while he was out of town. When Sharon and Jay had gone over to Bob’s for dinner, he remembered Sharon going to his bathroom and weighing herself to see how much she had gained during the pregnancy. This detail was especially tormenting to him. There was a sense of aliveness, of momentum and possibility, of bodies expanding, of things being good and on track. “You know, I guess I was lucky.”

“I thought about how much water had been stolen from the farmers. There’s no nice way to put it, but that’s what happened.”

I was curious to know if it had been hard to write the film in that wild and desperate moment, or if focusing on a creative act had been a way for Polanski as a collaborator to avoid reflecting on his losses. “It really didn’t affect the writing of the movie. He didn’t talk about it, but it was there. After it happened a curious thing occurred with Roman. Each time he would see somebody he hadn’t seen since before the murders, Sharon died for him all over again. The Manson killings stunned us. I remember trying to reach Jay the morning after and it was such a shock when I found out that I would never be able to reach him again.” I wondered if his relationship with Roman changed after that, but Bob replied in his usual matter-of-fact tone: “No, Roman’s a tough cookie. I mean, he had survived a lot by that time, you know. He survived World War II. He was very resilient and probably still is. I think he’ll outlive us all.”

Robert Towne and Roman Polanski worked every day on the film at the house of cowboy-Western actor George Montgomery. “We used the doorway to the office and wrote down the scenes that were in the script. Whatever we were doing, we would pin to the doorway and then just move the pieces of paper around.” “The original Post-its,” I suggested. “Yes, that’s what it was.” When the film was completed, Bob could only focus on what he thought was wrong with it. “But gradually I began to see that despite all my worries, the film was there, the vision had been translated. It had its own life. I remember sitting down and thinking: Son of a bitch! I guess we did it! The feeling was quickly followed by: No! It’s a fucking mess! And then again: Wait, I guess we did it!” Chinatown is widely considered to this day the best screenplay ever written. I wondered whether Bob ever imagined such enduring veneration. “I thought it was a pretty good screenplay, but I remember being shocked at an early screening with a couple of critics who spoke glowingly of it. It was unusual that they would even speak to you after a screening.” Out of all the people who might have been offended by the film—I remembered an article describing the granddaughter of William Mullholland’s indignant reaction to it—Department of Water and Power representatives were the most triggered. I heard a story about someone from the department who had seen it and said something akin to, “You know, that was really fake. There was never any incest involved.” Bob laughed. “I mean, nobody ever thought much about the DWP until that movie. It wasn’t something that was considered potentially scandalous material. It was the water department! And when the water arrived and Mulholland said those words, ‘There it is. Take it!’ he thought he was doing a good thing, which he was in a way. It was a meaningful sentence.”

I’ve been thinking about that sentence a lot and how symbolic it was. This gesture of pointing to something that you wanted to own and commanding it into existence was one of the stepping stones of the American capitalist ethos, an ante litteram “click.” Author David L. Ulin has written extensively about that Mulholland command: “It’s two sentences right there, five words. Yet it’s kind of the whole of the complexity of the city.” Ulin thought Mulholland’s words should be the city’s motto, “emblazoned on every police car… embedded in the city seal. It says all there is to say about the place, about the myths and what they mean and what they will never mean, about the promise of the city, which is both true and the most pernicious sort of lie.” To him the words were an initiation, not just about civic leaders using public mechanisms for private good or about water’s fast and mysterious doings, but they also established the city as we know it, the city that we now think of as inevitable sprawling megalopolis.

On that trip through California, I often wondered what would have happened had Mulholland not been tempted by the alpine water of the Owens Valley, if Los Angeles hadn’t gotten a chance to sprawl. Bob didn’t even stop to ponder that. “I mean, it’s happened. You can’t unring that bell. As in the history of histories: Somebody is always getting fucked, you know.” I looked around the room and paused again at the iconic Chinatown poster behind him. I always loved its opiate quality. The steamy purple logo, Gittes’s pinstriped suit in the corner, his wafting cigarette smoke evoking the flow of water. Water is everywhere, but it’s subtle. I asked Bob about Jack Nicholson, and he smiled, affectionate and wistful. “Jack still lives up on Mulholland Drive.” Nicholson has lived on that property since 1973, the year before Chinatown came out. “It would be great to see him sometime.”

The sun was setting and I had a plane to catch. Bob and I squeezed each other’s hands. He had seen and done it all, yet his mind was still moving fast. A TV adaptation of Chinatown, a prequel, was in the works with David Fincher. “I have been called a romantic,” he told me. “I don’t think I would ever have called myself that, but you can’t really argue with what people call you, you know?” I wondered how many dreams of his had been shattered, how many scripts had not been approved, how many times he’d been on the beach of disillusionment. He smiled and shook his head. “Oh, my God, you know, rejection is kind of a way of life here. And all I can suggest is pay no attention to it. Everybody suffers rejection, and you mustn’t ever think of it as a comment on you—it’s just the way people are. If you’re not known, you’re nobody, and that’s the way it is. Most of the movies I made were rejected multiple times, but I never stopped insisting. Stubbornness is necessary. I think you’ve got to believe in what you're doing, and as far as rejection goes, get used to it and try to ignore it. Just fuck it!”

And with Bob’s “Fuck it!” in my heart, I felt lighter leaving his house. “Fuck it” might be the opposite of “Take it,” but to survive in Los Angeles you had to assimilate both.

From left: the author’s copy of the original construction manual for the Los Angeles Aqueduct, published in 1916; William Mulholland, the engineer behind the Los Angeles water system; the program for the Los Angeles Aqueduct’s opening ceremony in 1913; headlines announce the opening of the aqueduct in The Los Angeles Times, 1913