Top 10: Movie Offices

By Robert Bound

Severance, created by Dan Erickson, 2022—present

Top 10: movie Offices

By Robert Bound

Onscreen workplaces—from the dystopian to the hyperrealistic—reveal our attitudes toward corporate life

Remember the death of the office? Seems that was greatly overblown. Amazon has called staff back for a five-day workweek and Jamie Dimon, boss of JPMorgan Chase, has spiced up the conversation with his complaint that “I’ve been working seven days a goddamn week since Covid, and I come in and—where is everybody else?” Meanwhile, the creepy brilliance of Severance, with its fluorescent glare and labyrinthine corridors, has provoked audiences’ love-hate relationships with their own work lives (and landed Apple TV+ its best-ever viewing figures in the process). Perhaps Severance is so satisfying because it’s only a little more stylized and surreal than our own experience. Offices attract and appall us, their rhythms and rituals soothing and maddening in equal measure.

This inherent tension makes for great cinema. In Jacques Tati’s Playtime (chosen by Galerie’s newest curator, Christos Nikou), Monsieur Hulot is a man out of time, bumbling around a future Paris office that’s all hard surfaces, automation and sterility. The idea that offices have morphed from efficient spaces to inhuman ones is common onscreen: In The Apartment, Jack Lemmon’s Bud has a nervous twitch in sympathy with his jittery calculator, his arrival and departure strictly timed to ensure the efficient processing of personnel—something Severance also glories in, with the elevator as the wardrobe-like gateway to a Narnia of despondency. But not every depiction is a dystopian fantasy. The office in 9 to 5 is a feminist hotbed of a 1980s workplace, as defined by recognizably human problems as the fashion magazine offices of The Devil Wears Prada are by tightly controlled creativity. Which films serve up the best office drama? Set your OOO now and read on.

![]()

Jacques Tati (center) in Playtime

![]()

Surveying the offices of the future in Playtime

1. Playtime, dir. Jacques Tati, 1967

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot, the immortal pratfall-prone (and seemingly jobless) flaneur, makes his way around the sort of hyper-stylized version of Paris that would have made Fritz Lang green with envy. Tati worked with production designer Eugène Roman to construct a gargantuan film set of entire buildings, streets and traffic lights (all of which required a mini power station) to exquisitely render his slick modernist city. Of course, Monsieur Hulot doesn’t get it: Throughout Playtime he’s an innocent abroad, an elegant but ill-equipped explorer in raincoat and trilby, wrestling with glass doors, buses and travel agencies selling vacations to Mexico, Stockholm and Hawaii—all of which are advertised as Soviet-style tower blocks shot at slightly different angles. Playtime’s pièce de résistance is its depiction of the office of tomorrow. The hum, whir, flashing lights and sci-fi sound effects of the foyer appall Monsieur Hulot. The monochrome corridors are endless. Why is the floor as slippery as an ice rink? Where is the carpet? Why are there boxes of employees, packed like sardines? Aha: cubicle culture as imagined in the mid-1960s! In the end, Playtime is a mesmerizing ballet of subtle slapstick leavened by a future-shock froideur—a world of man-made surfaces but not really made for men at all.

Jack Lemmon in The Apartment

2. The Apartment, dir. Billy Wilder, 1960

Jack Lemmon’s C.C. “Bud” Baxter is a conflicted salaryman bullied into lending his dwelling to his bosses for their extramarital daliances—including, gallingly, one with Fran (Shirley MacLaine), the object of his affection. So Bud finds himself spending a lot of time at the office, way beyond the working day: “The hours in our department are 8:50 to 5:20. They’re staggered by floors so that 16 elevators can handle the 31,259 employees,” as he informs us in his punctilious opening monologue. Bud is an insurance man for Consolidated Life of New York who works “on the 19th Floor, Ordinary Policy Department, Premium Accounting Division, Section W, Desk number 861” and whose routine is as gratingly precise as those details suggest. Sure, Bud can sit at his desk, even though it seems better designed to showcase the large Friden calculator whose staccato jitterings he mimics in the office yet haunt him on the outside. Bud’s superiors, meanwhile, luxuriate in city-view corner offices with their feet up on desks, designed around the decision-making tools of ink stamp and telephone. In long-shot black-and-white, Bud’s office floor seems endless, a low-ceilinged cathedral of airless industry, with a horizon so distant it shimmers as a pale heat haze. Row upon row of suited or skirted minions attend to clattering keyboards, natter in elevators and wisecrack to survive. Wilder and Lemmon’s attention to routine and the seeming pointlessness of the toil is droll and chilling. To trumpet fanfare, Bud wins a promotion to a windowed office with a hand-lettered sign—“2nd Administrative Assistant”—but also, later, after another promotion, a warning from the big boss: “Normally it takes years to work your way up to the 27th floor, but it only takes 30 seconds to be out on the street again.” Has the stick-and-carrot of corporate reality ever been so sharply defined?

“You clock in, but you can never leave.”

The ruthless efficiency of Brazil’s HQ

3. Brazil, dir. Terry Gilliam, 1985

Terry Gilliam’s maximalist opus on drone-dom and longed-for escape imagines the office as a theater of dystopian drudgery. Center stage is Jonathan Pryce’s Sam Lowry, the epitome of the unassuming beaten-down beta male who, when urged, “You must have hopes, wishes, dreams!” can only blurt out, “No, nothing! Not even dreams!” Lowry’s world revolves around an office of undefined grind centered on crunchingly analog early computers with monitors too small to read without unwieldy magnifying screens—all symptomatic of a workplace seemingly designed to drive you nuts. Norman Garwood’s sets mix elements of retro-futurism, steampunk and industrial gloom to offer up an atmosphere somewhere between the fascistic chill of Michael Radford’s 1984 and the sweaty paranoia of Wolfgang Petersen’s original Das Boot miniseries. When the dreams Lowry claims he doesn’t have start to come true? God, we’re rooting for him. Gilliam, of course, has other ideas.

The secretarial pool alliance of 9 to 5

4. 9 to 5, dir. Colin Higgins, 1980

There is a lot more overtime in this black comedy gem than the hours advertised in the title. With a screenplay co-created by Patricia Resnick (with director Colin Higgins), who had previously written the film treatment for Robert Altman’s 3 Women, the film is all at once a workplace comedy, a revenge-fantasy caper and a feminist gut-punch. Lily Tomlin, Jane Fonda and Dolly Parton are, respectively, a smart office lieutenant passed over for promotion, a recently divorced new recruit, and a misunderstood secretary bearing the brunt of office gossip due to the boss’s wandering hands. While the story does get a little blown off course, it’s the style and substance of the offices of Consolidated Companies (thank you, The Apartment) that are the soul of the piece: Chunky filing cabinets and well-ordered desks set the scene for the morning ritual of removing dustcovers from typewriters, brewing the boss’s coffee and preparing to do battle with the everyday sexism of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Other than the chief’s knock-and-enter domain decorated in a mahogany, gentleman’s-club style, Dean Mitzner’s production design is light on symbolism, allowing us to enjoy the whip-crack dialogue as the women gossip, bond and eventually scheme their way to the top. Plus, if you want a perfect taxonomy of the secretary fashions of the era, 9 to 5 has enough pencil skirts, ruffle-fronted blouses and salon-fresh blowouts to sway any industrial tribunal.

.jpg)

5. Zodiac, dir. David Fincher, 2007

David Fincher’s San Francisco serial-killer procedural mines the style of the eras it spans, from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, showcasing the manners, hairstyles, habits and offices of both a newspaper and a police force. Robert Downey Jr. is a louche investigative reporter teamed with Jake Gyllenhaal’s nervy cartoonist as they both dive too deep in attempting to uncover a series of grisly murders confessed to in coded communications. Mark Ruffalo and Anthony Edwards are hard-boiled cops who are similarly sucked into the vortex. The film’s production design, by Donald Graham Burt, is grounded in quietly stylish workplaces in what must be a hundred shades of beige, brown, yellow and gray that slowly become whiter, brighter and more shrill as we travel through time. Both the cop shops and the newspaper HQ possess a loose-tied formality but are also spaces where the individual can thrive: Desks are lightly personalized, the occasional art print joins certificates on the wall, uniforms have largely been dispensed with. Zodiac’s offices are not gulags of the soul, but rather the least-worst places for these single-minded men to spend long nights gnashing their teeth over the crimes that are their shared obsession. Cops, journos, murderers: They all live and die. The office? The lights are always on.

LaKeith Stanfield in Sorry to Bother You

6. Sorry to Bother You, dir. Boots Riley, 2018

If you thought that sitting at a desk all day doing something that may not add up to anything is a bit sad…well, try telemarketing and its horrible poetry: “Good morning, how are you today? Sorry to bother you. I am—.” Expanding on that premise of indignity, Sorry to Bother You is an ingenious, joltingly surreal comedy set in a call center, that notorious workplace where every conversation is scripted and, of course, every call is monitored for quality-control purposes. LaKeith Stanfield plays telemarketer Cassius Green (first name pronounced “Cash-is”—get it?), prone to gazing longingly at the gilded art deco elevator reserved for the “elite brigade” of successful Power Callers, denizens of the hallowed top floor, before climbing the stairs to his own zone of fluorescent-lit, dropped-ceilinged workstations of shame. After he’s advised to use his “white voice”—a kind of aw-shucks, college-boy confection—the orders come rolling in and Cassius arrives, via that Gatsby elevator, to a top floor revealed as a pleasantly bland office in the cookie-cutter contemporary mode of exposed concrete and glass-walled breakout pods—as the firm’s dreadful true purpose is disclosed. Thematically, it’s still Jack Lemmon’s Bud entering his Faustian pact for survival and promotion. Stylistically, it’s a darkly psychedelic cautionary tale. You clock in, but you can never leave.

![]()

The Devil Wears Prada’s immaculately organized magazine editor (Meryl Streep)

![]()

The editor’s harried assistant (Anne Hathaway)

7. The Devil Wears Prada, dir. David Frankel, 2006

Despite the 2006 release, David Frankel’s take on fashion publishing’s most prestigious title—Runway magazine—has a decidedly ’90s feel: We have power dressing, power lunches and, naturally, power offices. In a workplace where the corridors and elevators can be home to catty put-downs and withering looks, the best and bitchiest stuff is reserved for the editor in chief’s steely aerie, in which Meryl Streep’s Miranda Priestly is just slightly more queenly than Stanley Tucci’s Nigel Kipling, a dispenser of mal mots. Priestly’s droll hauteur—“Is it impossible to find a lovely, slender female paratrooper?”—is bolstered by her office domain of artfully minimalist knickknacks, fluted bookcases in bright white gloss, and black-and-white portraits that look a lot like Vogue’s golden age of Beaton, Horst, Bailey and Newton. Outside the throne room, assistants sit at nervy readiness behind crammed-in desks arranged so that coffees can be quickly fetched and cars instantly ordered to avoid acid chastisements. As art director, Tucci’s office is much warmer: all mood boards, light boxes and sample rails—a sign that perhaps his world of creative and tactile decisions is a more noble calling than just being bossy. It’s all good, nasty fun in an office era in which “icy” was misread as “classy.”

“A world of man-made surfaces but not really made for men at all.”

.jpg)

8. The Lunchbox, dir. Ritesh Batra, 2013

When is an office romance not an office romance? When, despite the spiciness, it’s all completely anonymous. Ritesh Batra’s open-hearted tale revolves around two lonely souls connecting due to a series of serendipitously misdirected deliveries in Mumbai’s lunch-delivery service. Millions of tin tiffin boxes are sent out daily from the kitchens of private homes via a mostly two-wheeled and two-legged courier service to a waiting spouse at their desk. Although affectingly romantic—will widowed salaryman Saajan (Irrfan Khan) and underappreciated wife Ila (Nimrat Kaur) meet?—The Lunchbox is also a classic worker-bee film: Saajan’s job is all paperwork and bureaucracy. His office is an almost Dickensian, old-school Indian throwback of creaking desks and archaic filing systems. Has Saajan let himself go to seed, surrounded as he is by these old ways and bad habits, and with his curmudgeonly take on his juniors’ little office quips and small courtesies? By contrast, the process of the tiffin deliveries from kitchen to desk is feverishly yet lovingly presented at every turn: Whatever the job, it must be done.

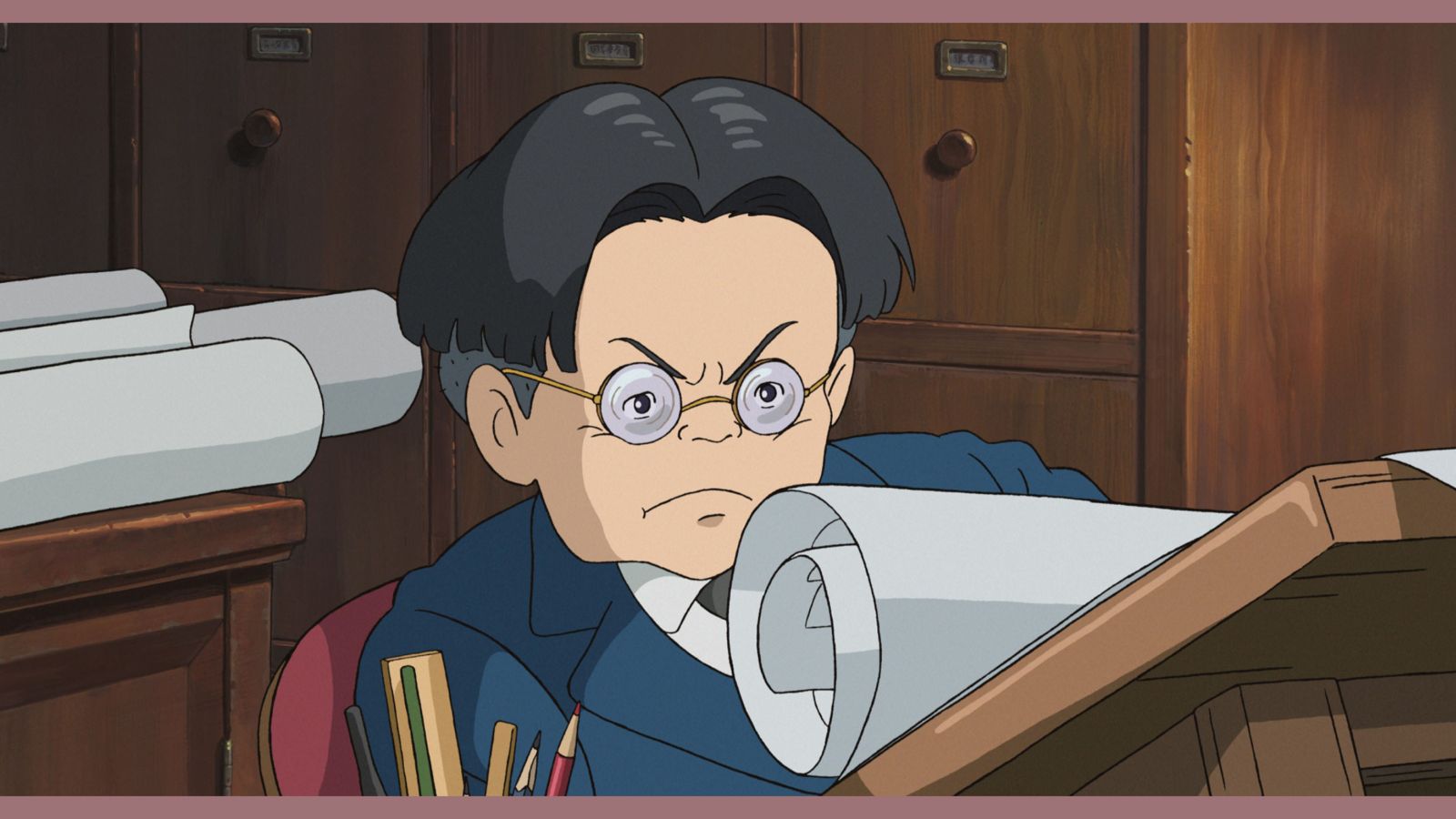

The offices of early-20th-century engineers, as imagined by Hayao Miyazaki

9. The Wind Rises, dir. Hayao Miyazaki, 2013

Hayao Miyazaki’s late-career epic is a love story—inspired by the life of Japanese aviation engineer Jiro Horikoshi, creator of the A6M WWII fighter plane—matched by the filmmaker’s affection for engineering and design. We see impeccably realized offices filled with drawing boards and blueprints, old-school slide rules and protractors, while the aspirant airplane designer Horikoshi realizes his dream to mastermind what became the Mitsubishi Zero, that scourge of the skies of WWII’s Pacific Theater. Miyazaki’s famous love of nature, and genius at re-creating its movement and majesty in hand-drawn animation, is present throughout the film, as is his respect for its heedless power: The story is set against Japan’s real-life early-20th-century upheavals of earthquakes, disease and war. Miyazaki appears to simply adore the office in which he’s placed his lead character. The collegiate feel at the desks—young men in crisp white shirts, ready with sharpened pencils for sleepless nights of drafting ahead of them—is intoxicating and heartening until you pinch yourself and realize, Oppenheimer-style, just what it is they’re building. But Miyazaki’s love letter to care and craft, whatever the shape of their outcome, is a true testament to skill. And where else will you hear your hero declare to a rapt room, “This is Mr. Hirayama, our production engineer—he’s going to tell us about the new rivets”? Riveting!

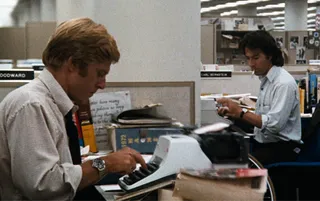

Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as hard-charging journalists in All the President’s Men

10. All the President’s Men, dir. Alan J. Pakula, 1976

If offices are zones where meaningful work can be done, then Alan J. Pakula’s spellbinding Watergate drama could claim to be the ultimate office film. Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) are the restless, tireless reporters who eventually persuade the head honchos at The Washington Post to print as much as they can of what is a major Republican “ratfucking” sabotage operation at the infamous Watergate complex. The film is a masterpiece of eerie watchfulness and late nights spent making connections and worrying over transcripts; the ties loosened, the stubble getting bushy on the chin. The Post—the newspaper of record at the time—is depicted in an office of classic, no-frills sophistication: It’s a well-oiled machine in which reporters sit in an open-plan arrangement, with editors in side offices where they can harrumph and ask for a tighter write-up in relative privacy. It hums along efficiently and, like a Vegas casino, is strip-lit to the point where no one seems to know if it’s day or night. Meanwhile, in the small hours, Woodward’s and Bernstein’s apartments become homemade offices: coffee tables overflowing with yellow legal pads, ashtrays dangerously full. It’s again a film of process and patience. David Fincher appeared to be a fan—watch this film then Zodiac, and you might experience déjà vu.