The New Ghana Film Scene

By DK Nnuro

The Burial of Kojo, dir. Blitz Bazawule, 2018

The New Ghana Film Scene

The next generation of talent revives a regional industry

By DK Nnuro

October 25, 2024

In the opening scene of Blitz Bazawule’s 2018 film The Burial of Kojo, the titular character sits on a seashore forlornly watching the tide lap at a powder-blue Volkswagen Beetle stuck in the muddy tideline. It is obviously morning, with everything cast in new-day pensiveness. A certain brand of American moviegoer might project onto Kojo a rock-and-a-hard-place storyline, perhaps something The Hangover-esque—indeed, the car has been decorated for a groom and his bride, garlanded in festive pops of red. Is Kojo the groom? Where might his bride be? Oh, and exactly how good a time did this dude have last night to find his car here?

![]()

The opening scene from The Burial of Kojo

![]()

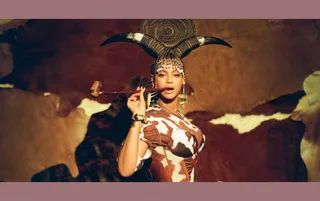

Black Is King, dirs. Emmanuel Adjei, Ibra Ake and Blitz Bazawule, 2020

The voice of the film’s narrator, Esi, Kojo’s daughter, breaks in. Because the voice is somber and poetic, it has the effect of discrediting the presumption of that usual Hollywood set-up: Here is the aftermath of debauchery-gone-too-far; now let us show you how we got here. The film, we quickly learn, is more concerned with the porous separations between reality and dreams—and magic, fantasy and even the afterlife. Right on cue, the Volkswagen Beetle magically goes up in flames with Kojo standing close to it, then the unnerving scene cuts to Kojo seated back on shore with a fire raging behind him.

The Burial of Kojo is written, directed and scored by 42-year-old Accra-born Blitz Bazawule, a figure probably best described as a polymath: filmmaker-cum–hip-hop artist–cum–music-video director–cum-novelist. Under the stage name Blitz the Ambassador, Bazawule has released four studio albums. He directed parts of Beyoncé’s 2020 visual album Black Is King. In the summer of 2022, he published his first novel, The Scent of Burnt Flowers (set in Ghana), the rights to which have been obtained by FX for a six-episode limited series. In 2023, Bazawule’s film adaptation of the musical The Color Purple, was released to critical acclaim, with Oprah Winfrey and Steven Spielberg among the film’s producers; he is also slated to direct Black Samurai for Warner Bros., based on his own script.

The Burial of Kojo premiered on Netflix in spring of 2019, making it the first Ghanaian-produced film to appear on the streaming service. The film was also the Golden Globes’ first Ghanaian entry. Bazawule, who moved to the United States in 2001 to study business administration, returned to Ghana in 2017 to shoot the film, which took 23 days. In it, young Esi lives with her mother, Ama, and her father, Kojo, in a lake village made up of small houses built on stilts. In real life, this lake village is Nzulezu, located on the Gulf of Guinea. The other shooting location was Tarkwa, a mining town in the Western Region of Ghana, an apt choice considering the inspiration that Bazawule cited during a 2017 TED interview (Bazawule is a TED senior fellow): “I happened to chance on a [newspaper] story about a group of young miners that had been buried alive. And right there and then, I was like, Wow, this is crazy, there’s something to this, because I felt like I wasn’t getting the full story.”

“Ghana has a way of humbling artistic ambitions. It is impossible to do anything worthwhile in Ghana without a surfeit of toil.”

The Burial of Kojo spans an hour and 20 minutes. It flouts linearity and traditional storytelling to such a degree that a coherent synopsis is nearly impossible. The common instinct is to build out from the film’s halfway point: A man named Kojo is trapped deep in a mineshaft by his vindictive brother. His young daughter sets off on a hero’s journey to find him. Esi’s journey is mystical and fablelike, awash in hypnotic imagery, typified not only by the flames and rising tide in the film’s opening but by a scene capturing a place between the afterlife and the land of the living, where a white-clad Esi finally comes to terms with the fact that she is the only person who can save her father. Kojo is symbol-laden, to put it mildly, and the most significant symbols are the birds that Bazawule uses to tell a timeless tale of good versus evil. Early in the film, an old blind man leaves a sacred white bird (good) in Esi’s care, which she is supposed to protect from the black crow (evil) that she sees in her dream. This crow, it turns out, is a man dressed in a crow costume who rides a horse. We first encounter him in a scene that is literally flipped on its head and accompanied by the score of an old spaghetti Western. Lightning soon strikes, and the scene turns upright, allowing for our crow-costumed cowboy to make his slow approach.

The hint at the spaghetti Western, coupled with the American-style opening, shows that Hollywood has strongly influenced Bazawule’s cinematic imagination—it was only a matter of time before he made his way there with Spielberg and Oprah by his side. Perhaps because of Bazawule’s American sense of bigness, in 2017 he characterized Kojo as the “first non-foreign film of this magnitude and scale to be produced in Ghana.” By “magnitude and scale,” Bazawule must have meant his own vision and ambition; certainly not the film’s budget. He completed the film’s principal photography on a shoestring. For post-production work, he resorted to a Kickstarter campaign that raised $78,291.

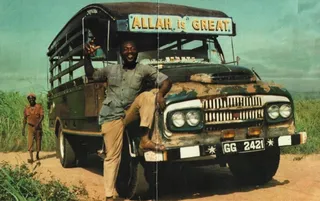

Ghana has a way of humbling artistic ambitions. It is impossible to do anything worthwhile in Ghana without a surfeit of toil. When asked during his TED interview what it was like to shoot there, Bazawule responded in a particularly Ghanaian way, albeit with a narrow focus on the country’s film industry: “It’s always a challenging process, but what makes it extra challenging here is that the film infrastructure is very limited, so most of the things that you need, you have to fly in.” King Ampaw, a veteran director considered one of Ghana’s most important filmmakers, echoed this reality when I met with him in Ghana in January 2023 to ask about his first film, 1983’s Kukurantumi: Road to Accra: “Luckily, at that time, the Ghana Film Industry Corporation [GFIC] was still in existence…which means I could access staff who knew about filmmaking. I had the technicians. I had some of the equipment. I had some crew who knew about film production…but I brought key people in from Germany. That included a main cameraman and a main sound man because sound production at that time was one of the basic difficulties for African filmmakers. I also brought a lighting man and even a production manager. All of them were assisted by the crew from the GFIC. This was the only way to make the process a little easier for me.”

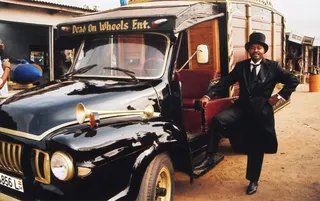

Left: No Time to Die, dir. King Ampaw, 2006; Center and right: Kukurantumi: Road to Accra, dir. King Ampaw, 1983

After Ghana gained independence from Britain in 1957, the country’s first prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah, set the country on a course of rapid development. In the film sector, Nkrumah nationalized film production and distribution. For £275,000, the country’s newly formed Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) acquired privately owned distribution company West African Pictures, a holdover of the colonial era. When Ghana became a republic in the mid-1960s, the IDC was liquidated, and its film exhibition arm was folded into a new film production company to become the State Film Industry Corporation (SFIC). Charged with distributing and screening local and foreign films, the SFIC owned and managed eight movie theaters across the country. The SFIC produced newsreels, documentaries, feature films and television content that centered on Ghanaian self-determination, national pride and, of course, the Nkrumah government’s political interests and propaganda.

In 1966, Nkrumah’s government was overthrown by a group of soldiers who instituted a military dictatorship under the banner National Liberation Council (NLC). The NLC made notable headway in commercial feature film production. One of its outputs, Egbert Adjesu’s I Told You So, released in 1970, is now considered a classic. The film is set during the early period of independence and is a comical indictment of the country’s emerging elite, who are given to postcolonial excesses and corruption. Additionally, I Told You So concerns itself with the increasing rejection of traditional Ghanaian values in the modern race for wealth. The film was the kind of hit that should have inspired the NLC to continue to invest in commercial productions. But in 1971 the NLC turned the SFIC into the Ghana Film Industry Corporation (GFIC), which continued to pour money into content that promoted the government’s propagandist goals, with little interest in scaling or sustaining its commercial film arm. With GFIC’s eventual unsustainability in the commercial sector, a new era of independent film production emerged.

The first of these independently produced films was 1980’s Love Brewed in the African Pot. Directed by Kwaw Ansah and among the first there to be shot on celluloid, it is a rendition on what was by then the primary thematic preoccupation of not only Ghanaian filmmakers but filmmakers across Africa: indicting the elite and the pursuit of wealth and Western ideals at the expense of traditional cultural practices. Love Brewed in the African Pot employs a Romeo and Juliet–like storyline of star-crossed lovers to conduct its indictment. Ansah completed his script in 1974 but for several years struggled to find funding from a nearly bankrupt GFIC and Ghanaian banks. Finally, his father-in-law put up his house and cocoa farm as collateral for a bank loan.

In 1989, nine years after Love Brewed in the African Pot came out, Heritage Africa—widely considered Kwaw Ansah’s masterpiece—was released. It was funded by three Ghanaian banks that raised about half a million U.S. dollars, a still-unbeaten record for a Ghanaian production. In his doctoral thesis, “Cinema in Ghana: History, Ideology and Popular Culture,” Vitus Nanbigne, widely considered Ghana’s foremost film scholar, cites the film’s title with an ellipsis: Heritage…Africa. The ellipsis is a curious one and recalls the writer Jelani Cobb’s rub with the term African-American, which Cobb describes as being marked by “a fundamental dissonance, [as the term represents] two feuding ancestries conjoined by a hyphen.” He suggests that perhaps the two words—African and American—be separated by an ellipsis to signify enduring tensions between Black people with immediate African ancestry and those without. Heritage’s ellipsis frames an adjacent tension: The film, much like Love Brewed in the African Pot, skewers Ghanaian preferences for white colonial ideology and cultural practices. It is a cautionary tale about the grave consequences of this choice.

![]()

Ama K. Ababrese and Cynthia Dankwa in The Burial of Kojo

![]()

Potato Potahto, dir. Shirley Frimpong-Manso, 2017

To sustain its commercial film production, the GFIC adopted a model of co-productions with European producers. The model failed, with big productions like 1973’s The African Deal, a collaboration with Italian company Ital Victoria and directed by Italian director Giorgio Bontempi, flopping and exacerbating GFIC’s debt issues. Around that time, Kwaw Ansah started looking for funding for Love Brewed in the African Pot, and perhaps he could have found better luck with the co-production model—especially because he was educated in both England and the U.S., graduating from the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in 1965. But he was wary of such collaborations infringing on his creative freedom.

King Ampaw, Ansah’s close contemporary, chose to embrace the co-production model when he returned to Ghana after his studies in Germany, where he graduated from the Academy of Television and Film in Munich in 1972. His classmates included Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders. Ampaw has long since lived in Teshie Nungua, a suburb of Accra. Sitting across from me at his dining table, he explains why he was eager to return “home” after his time in Germany: “I knew that as a Black man, why should I stay in the white man’s land and make films? I was the only Black person in my class. There were very few Black people in Germany in those days. What was I going to do there? So I decided to come back home and try to make stories here.” After he finished the script for Kukurantumi, Ampaw called on his German contacts. “They helped me fund the film.”

Notably, Vitus Nanbigne also employs an ellipsis when citing Kukurantumi in his film study Kukurantumi…Road to Accra. Here, the tension captured by the ellipsis has less to do with the concerning takeover of Western influence. Rather, Kukurantumi is a film interested in the tensions between village and city life, and how the big city’s promises are often illusory. The ellipsis, then, manifests the literal road between the village (Kukurantumi) and the city (Accra). It is this road that Abena, one of the film’s central characters, takes to Accra, where she can avoid her overbearing father and where she believes she will make a better life for herself. Accra, though, proves to be a hard place to survive.

Wim Wenders, Ampaw’s classmate, is one of the preeminent practitioners of the road film. I am compelled to make the case for a shared artistic vision, so I ask Ampaw if he considers Kukurantumi to be a road movie. “I’m for road movies,” he begins, “the ’60s, Easy Rider and the rest…we grew up on them…think of the word—movies, move…I find it more interesting to travel with the story.” We get off track a bit. But he soon returns to the topic. “What were the best films when we were younger? They were the cowboy films! Because of the horse, they were able to transfer the story from place to place…movies are pictures, you can’t concentrate on one picture or one studio set. It’s better when you show many pictures!”

Released in 2006, No Time to Die was King Ampaw’s last film. Now 84 and plagued with health problems, he says that he moved on from the movie business “a long time ago.” He is familiar with Blitz Bazawule, though, especially with the fact that Bazawule is the founder of Africa Film Society, which, among its many efforts to revive a “dormant” (as Bazawule puts it) cinema culture in Ghana, hosts a film-screening series in Accra called “Classics in the Park.” No Time to Die was the December 2019 selection. When I tell Ampaw how much I enjoyed the film—it was my second viewing—he smiles wryly and I’m a bit stumped because I don’t know how the smile intends for me to proceed. Our conversation is winding down; I have taken too much of this generous man’s time. Driving home, I meditate on what was left unsaid, that other case for shared artistic vision closer to home I was not able to make. Because if Ampaw was shaped by cowboy movies, he ought to see the unique way Bazawule’s own shaping manifests in Kojo. Bazawule animates Kojo with a cinematographic mishmash that coalesces into an affecting experience. The film is a braided narrative, and one of the threads is a road narrative: Kojo is lured to Accra by his brother Kwabena on the promise of imminent wealth. Of course, as in Kukurantumi, Accra proves vicious.

![]()

Heritage Africa, dir. Kwaw Ansah, 1989

![]()

Love Brewed in the African Pot, dir. Kwaw Ansah, 1980

I am now in traffic, one of Accra’s mainstays. Upon further reflection, I realize that perhaps I was deterred from connecting Ampaw’s work to the current crop because, despite his obvious respect for Bazawule, his thoughts on the present state of Ghanaian cinema are wholly negative. “They are not serious,” he told me resolutely.

Limited access to funding has, in part, resulted in what the industry is today: a video feature film industry. In the essay “Ghanaian Popular Cinema and the Magic in and of Film,” cultural anthropologist Birgit Meyer writes, “since the late 1980s…formally untrained people of various backgrounds—from cinema projectionists to car mechanics—took ordinary VHS video cameras, wrote a brief outline, assembled actors (from TV or just ‘from the street’), and produced full-fledged feature films which appeared to be tremendously successful in urban Ghana, and especially in Accra.” This model still dominates today, even among formally trained filmmakers. It is a free-for-all that sometimes unfairly lumps the good with an inundation of the bad. Director Shirley Frimpong-Manso is an example of the good. Her film Potato Potahto (2017), about a divorced couple who decide to continue living together, started streaming on Netflix in 2019, not long after Kojo premiered on the platform. Frimpong-Manso is celebrated for breaking new ground as a leading filmmaker who has shattered all kinds of glass ceilings. Inspiringly, her success is entirely locally made—she was not educated abroad.

The traffic has cleared and I’m almost home. Despite today’s date—January 4, 2023—it is still December in Accra, the holiday season in full swing until mid-January because Ghanaians have a special love for the holidays. In 2019, the holiday frenzy went up a notch with the launch of the “Year of Return.” The initiative encourages people of African descent to return “home” to Ghana. December is peak season for these returns and Black American celebrities in particular have helped elevate a December journey to Ghana as a badge of relevance and status. Dave Chapelle finally made it this year.

On the heels of this return season, it was announced that the sequel to the hit 2017 Hollywood movie Girls Trip would be shot in Ghana. In addition, Idris Elba, who starred in 2015’s Beasts of No Nation, which was shot in Ghana, announced during a February visit that he is working on a plan to build a film studio in the country to attract more filmmakers to West Africa (in October 2024, Elba confirmed his plan to relocate to Accra in the next decade “to bolster the film industry”). Perhaps Nanbigne is onto something with his ellipses. Perhaps Ghanaian cinema ought to be “Ghanaian…cinema.” On the horizon, it seems, is a new era. Since we don’t know how the story will play out, we’d do well to employ an ellipsis, intentionally signifying a story still coming together.