The Descendants of Dogme 95

By Bilge Ebiri

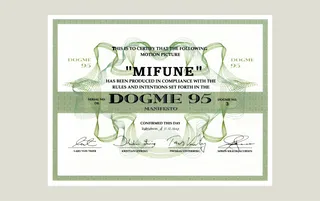

Mifune, dir. Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, 1999

The Descendants of Dogme 95

The outsize influence of an obscure Danish art movement

By Bilge Ebiri

June 25, 2025

When a collective of Scandinavian filmmakers at this year’s Cannes Film Festival unveiled a ten-point manifesto advocating for artistic purity, it was a case of déja vu. “In a world where film is based on algorithms and artificial visual expressions are gaining traction, it’s our mission to stand up for the flawed, distinct and human imprint,” read the group’s statement.

![]()

From left: Thomas Vinterberg, Kristian Levring, Søren Kragh-Jacobsen and Lars von Trier

![]()

Mifune’s official Dogme 95 certificate

The self-annointed Dogma 25 initiative, which calls for severe restrictions on technology in filmmaking, quickly received a message of support from one notable corner. “We wish you the best of luck on your march toward reconquering Danish film,” wrote Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg in a joint statement of intergenerational solidarity. This was perhaps no surprise, since Dogma 25 reignites a conversation—about the purpose and methods of filmmaking—first initiated by the two enfants terribles turned elder statesmen of Scandinavian cinema more than three decades ago.

On March 22, 1995, von Trier took the stage at a Paris panel celebrating 100 years of cinema and announced that he was inaugurating a new film movement. “It seems to me that for the last 20 years—no, let’s say 10 years—film has been rubbish,” he exclaimed, before standing up and, to the cheers of the crowd, tossing out a pile of red flyers (or, as he called it, “a bit of paperwork”) containing the so-called Dogme 95 Manifesto, signed by himself and the young Danish director Vinterberg. Alongside the manifesto was a Vow of Chastity, 10 rules to which any Dogme 95 picture would have to adhere.

These commandments ranged from the playful to the profound, insisting on principles of austerity and purity that eliminated stagecraft, embellishment and technological manipulation from filmmaking. One stated that the director could not be credited, while another demanded the camera be handheld. Yet another forbade something called “temporal alienation,” insisting that the films take place in the present moment. The half-smirk on von Trier’s face suggested that none of this was meant to be taken too seriously. But it was serious—a new religion of filmmaking.

Three years later, the first Dogme picture, Vinterberg’s Festen (The Celebration), about a huge family gathering that descends into chaos, took the 1998 Cannes Film Festival by storm, winning the Jury Prize. (Festen would go on to collect awards all over the world and vault Vinterberg into the top tier of international filmmakers, where he has since remained.) Shot handheld by cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle on an inexpensive Sony Handycam that seemed to drift haphazardly among the characters, The Celebration felt genuinely revolutionary—not least because, for all its manic, vérité grit, it was a story that could connect with regular audiences.

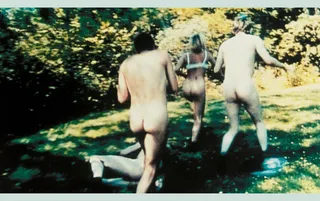

Also premiering that same year at Cannes was the more unhinged Idioterne (The Idiots), von Trier’s own Dogme effort, about a group of young men and women who pretend to be mentally disabled—an attempt at self-liberation via épater le bourgeoisie. This second Dogme film proved far more divisive, but it certainly got people talking—not just because of its style and subject matter but also because it featured a few frames of actual hardcore penetration during a climactic gangbang scene. Ever the showman, von Trier knew how to push not just viewers’ buttons, but also those of the festival-going international press.

Dogme 95 provided a compelling vision of cinema’s future. But even at the start one could identify the opposing forces that would ultimately compromise the movement. Yes, von Trier and Vinterberg were thumbing their noses at filmmaking conventions and reaching for a new kind of cinematic honesty. And yet here they were, clad in tuxes alongside their casts on the Riviera, bowing to the applause of gala attendees. “Suddenly, what was naked became fancy dress in Cannes, in 1998,” Vinterberg told me in 2021. “Suddenly, doing a Dogme movie was a ticket to every festival in the world.”

![]()

Open Hearts, dir. Susanne Bier, 2002

![]()

The Idiots, dir. Lars von Trier, 1998

Though Dogme 95 ultimately produced around 35 officially sanctioned titles between 1995 and 2004, as an international media phenomenon the movement never shone as bright as it did in this initial moment. However, some of the best Dogme 95 films would actually arrive later, as low- and zero-budget filmmakers around the world, many of them newcomers, tried their hands at making them. By 2005, the so-called Dogme Brotherhood—the four Danish filmmakers who oversaw the movement and, in its early days, vetted all the entries to make sure they were adhering to the rules—had already disbanded, moving on to new projects. (Vinterberg and von Trier had been joined by Kristian Levring, another relative newcomer, and veteran director and erstwhile pop star Søren Kragh-Jacobsen. A fifth Dogme “brother,” Anne Wivel—a woman—had left the movement early on because she was primarily interested in making documentaries.) But Dogme 95 had already served its purpose. “The whole idea was to make some kind of renewal,” Vinterberg said in an interview in 2001, explaining his decision to follow up The Celebration with the decidedly un-Dogmetic It’s All About Love (2003), an extravagant star-studded sci-fi romance. “A repetition of that would be very strange.”

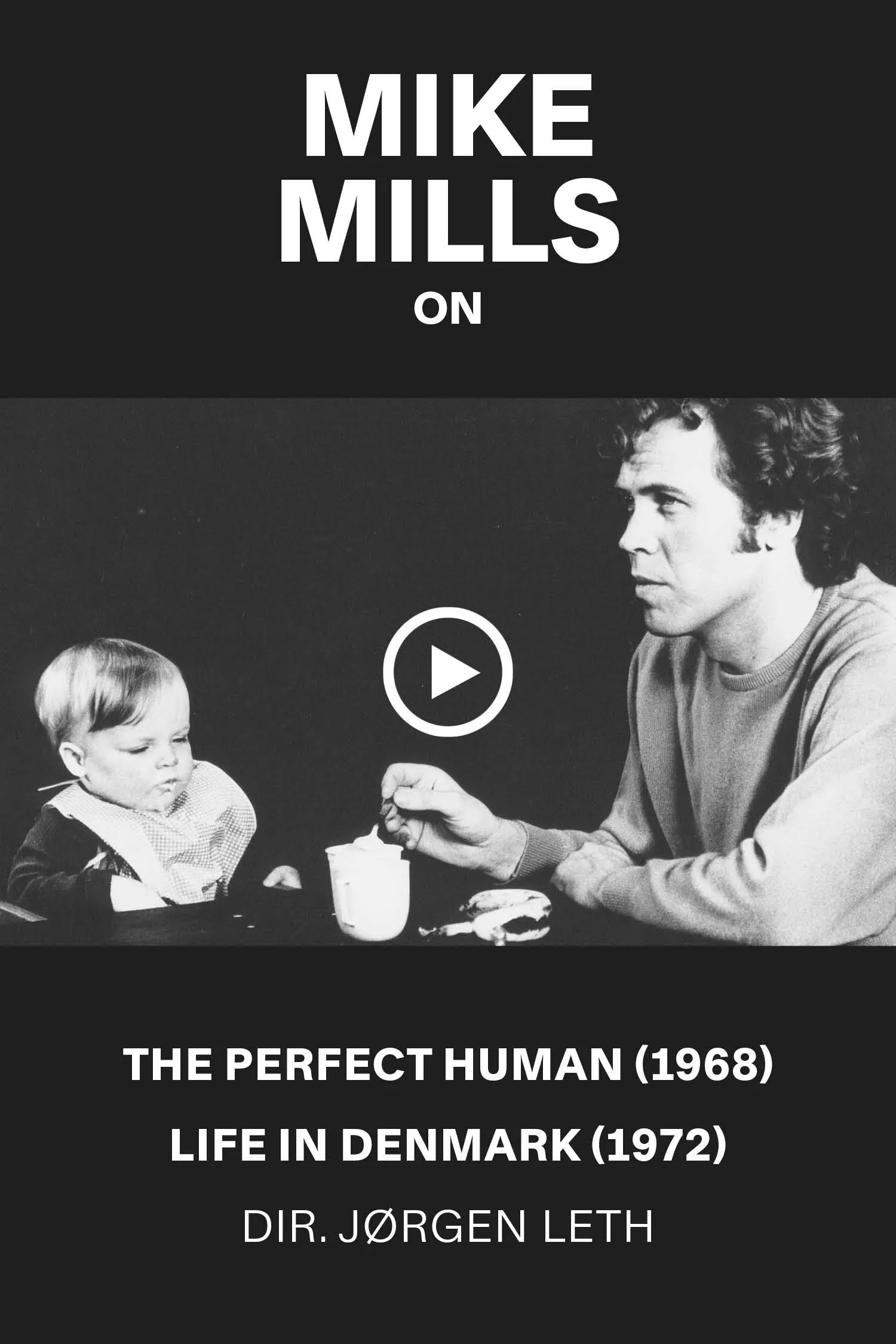

Dogme 95 was neither Lars von Trier’s first manifesto, nor his last. He had already written three of them, for his previous films The Element of Crime (1984), Epidemic (1987), and Europa (1991). The director had a propensity for making grand pronouncements and a flair for experimentation. In his hilariously revealing 2003 documentary The Five Obstructions, he tasks fellow Dane Jørgen Leth to remake Leth’s own seminal 1968 short The Perfect Human five different ways, each time with a new series of bizarre limitations set by von Trier. For the first obstruction, Leth had to make it in Cuba and not have any shot lasting longer than 12 frames. For the fourth obstruction, the film had to be animated.

Von Trier also seemed to have a fondness for self-flagellation. In his manifesto for Europa, he described himself as “LARS VON TRIER, A SIMPLE MASTURBATOR OF THE SILVER SCREEN” (caps his). He has always loved rules, limitations and constraints, and his work has constantly calibrated his auteurist, control-freak qualities against his desire to cede control entirely. (One of his more charming and underrated efforts is 2006’s The Boss of It All, an unlikely office comedy shot in so-called Automavision, in which the unmanned camera moves in ways chosen by computer.)

“By embracing video, the movement tapped into the worldwide frenzy around technology and revolution.”

So, what were the Dogme 95 rules? Here’s how the original manifesto, signed by von Trier and Vinterberg, put it:

1. Shooting must be done on location. Props and sets must not be brought in (if a particular prop is necessary for the story, a location must be chosen where this prop is to be found).

2. The sound must never be produced apart from the images or vice versa. (Music must not be used unless it occurs where the scene is being shot.)

3. The camera must be hand-held. Any movement or immobility attainable in the hand is permitted.

4. The film must be in color. Special lighting is not acceptable. (If there is too little light for exposure the scene must be cut or a single lamp be attached to the camera.)

5. Optical work and filters are forbidden.

6. The film must not contain superficial action. (Murders, weapons, etc. must not occur.)

7. Temporal and geographical alienation are forbidden. (That is to say that the film takes place here and now.)

8. Genre movies are not acceptable.

9. The film format must be Academy 35 mm.

10. The director must not be credited.

Von Trier and Vinterberg reportedly wrote up these rules in under an hour, over a bottle of wine, which might explain why they vary from the needlessly specific to the hilariously broad. But even if they might have seemed perverse at times, these limitations were an effort to get at the inherent truth of filmmaking, shedding all signs of artifice and manipulation.

“We made a revolt against mediocre conservative filmmaking. Also—Lars would never agree—against the mediocrity in ourselves,” was how Vinterberg put it years later. But beneath the perversity was also a kind of clear-eyed realism about the circumstances of putting together a movie. Note that almost none of the rules mentions editing. These directors understood that in order for the Dogme 95 idea to work, they would need a completely free hand in the cutting room. Not coincidentally, documentaries, which rely heavily on editing, could not be Dogme 95 films, even though many documentaries by their very nature adhere to these rules. What von Trier and his colleagues were really going for, whether they realized it or not, was ultimately quite simple: to bring to narrative filmmaking the apparent purity, authenticity and immediacy of vérité documentary. “My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings,” the Vow of Chastity declared.

So it’s ironic that, viewed today, many Dogme 95 films seem so stylized. Some of that is simply the passage of time. Back in 1998, the free-flowing, wide-angle, kinetic video cinematography of Vinterberg’s The Celebration felt not just bracing and new but raw and real. Today, however, it feels purposeful and in-your-face; it hasn’t lost any of its power, but the power goes in another direction now, away from realism and toward expressionism. Dogme 95 sought the death of the auteur, forbidding the ego attached to directing credits and vigorously proselytizing against aesthetics: “I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste! I am no longer an artist,” the vow declared. But so many of the Dogme films now seem like wildly aestheticized, almost pulverizing assertions of directorial control. The filmmaking—the personal taste and the artistry—isn’t transparent but ever present.

![]()

Lovers, dir. Jean-Marc Barr, 1999

![]()

Élodie Bouchez and Sergej Trifunovic in Lovers

The next two Dogme titles, Mifune (1999) and The King Is Alive (2000), by fellow Dogme brothers Kragh-Jacobsen and Levring, respectively, were in some senses more important to the immediate legacy of the movement, because they showed how the rules could successfully apply to a broad range of subject matters and styles. Mifune, about a Copenhagen man who returns to his family farm after his father’s death to care for his mentally disabled brother and becomes involved with a sex worker on the run, is funny, romantic, lush, even sentimental at times. The King Is Alive is an English-language survival tale (starring Jennifer Jason Leigh and Janet McTeer) about a group of tourists stuck in the Namibian desert who decide to restage Shakespeare’s King Lear from memory. Neither film displays the dizzying, free-form freneticism of The Celebration or The Idiots. Nor do they try to. Mifune was shot on 16mm (the rare Dogme effort to use celluloid, despite one of the rules stating that the film format had to be 35mm), and is, stylistically speaking, gentle and bucolic.

“It was pastoral, you had this broken-down farm, you had landscapes, flat fields in the south of Denmark,” observed Mifune cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, who also shot The Celebration and several von Trier films. “It would have been totally absurd for me to be running around with one camera on my head and one in my breast pocket.” Even so, Dod Mantle’s work on these Dogme movies demonstrated both his versatility and his ability to produce exceptional work with limited resources. It was no surprise that he was soon hired for bigger projects, most notably by Danny Boyle, who worked with the cinematographer on the digitally shot hit zombie thriller 28 Days Later and the Academy Award–winning Slumdog Millionaire, which became the first digitally filmed picture to win the Best Cinematography Oscar. (The innovation continues: For 28 Years Later, Boyle’s much-anticipated third installment of the postapocalyptic micro-franchise, Dod Mantle shot mainly on iPhone.)

By departing in ways big and small from the aggressive austerity of Vinterberg and von Trier’s rules, Kragh-Jacobsen and Levring proved that any film could adhere to the spirit of the Dogme rules and still retain its individual essence. That idea was cemented by 1999’s Lovers (officially, Dogme film #5), directed by frequent von Trier collaborator Jean-Marc Barr, which follows the tumultuous affair between a young French woman and an undocumented Yugoslavian immigrant. The film is a dose of romanticism that could have come out of the French New Wave, a movement that the Dogme manifesto had taken some not-so-veiled swipes at for having become too bourgeois.

Comparisons to the French New Wave also apply to Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners (Dogme #12), with its gentle story of the unlikely connections among a group of lonely individuals who meet regularly for an Italian class. Released in 2000, Scherfig’s movie was a genuine international phenomenon—perhaps the most widely seen Dogme title of all—with a reach well beyond the regular art-house crowd. Italian for Beginners even became a kind of political cause célèbre in Denmark, where right-wing politicians pointed out how much more successful this warm, modest comedy had been than von Trier’s own pugnacious entry. Scherfig’s picture didn’t have a political bone in its body, but its commercial success made it a convenient cudgel to use against the ostentatiously leftist von Trier.

From left: The King Is Alive, dir, Kristian Levring, 2000; Mifune, dir. Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, 1999; Italian for Beginners, dir. Lone Scherfig, 2000

Is it notable that some of the most successful and enduring Dogme 95 titles—including Italian for Beginners—were made by women, when so much of the Dogme ethos seemed to be a boys’ club? Judy Berman, in an excellent 2015 piece titled “What Dogme 95 Did for Women Directors,” suggests that Dogme’s machismo was overstated and notes that, thanks partly to the Danish film industry being “unusually welcoming” to women directors, the movement was actually a boon for female filmmakers. Women would go on to direct four of the 10 Danish Dogme films.

Susanne Bier’s Open Hearts (Dogme #28), released in 2002, proved to be one of Dogme’s more emotionally shattering films, following two couples who become tragically connected due to a devastating car accident. The parameters of the vows lend these films an emotional authenticity that validated them: The raw urgency of the filmmaking technique and the intimacy of the performances combine to transform far-fetched, potentially manipulative stories into organically moving works.

Which leads to a surprising truth: For all its renegade bravado, Dogme 95 in Denmark was ultimately a mainstream movement. The directors had come up through the industry, and most of them graduated from the National Film School of Denmark, where they mastered the art of conventional, tasteful filmmaking. (Hell, for all their talk of revolution and renewal, Vinterberg and von Trier had been influenced in their handheld aesthetic by the American TV show Homicide: Life on the Street.) The Dogme movies had state support, and producer Peter Aalbæk Jensen—von Trier’s boisterous, cigar-chomping producing partner and the cofounder of their company Zentropa—knew a marketable concept when he saw one. Aalbæk Jensen aggressively packaged Dogme 95 films for financing and distribution, and used the movement as a branding opportunity. Of course, it was partly because it was marketed so well that Dogme 95 proved to be so earth-shaking. Would The Celebration have been discovered by Hollywood and received a handsome distribution deal had it not premiered at Cannes? Would von Trier’s manifesto have made similar waves had he not chosen a prestigious international film panel at which to toss it into the audience?

In the U.S., however, Dogme 95 manifested as a more experimental initiative, with Harmony Korine’s chaotic and abrasive 1999 film Julien Donkey-Boy (Dogme #6), in which Ewen Bremner played a schizophrenic young man living in an abusive, possibly incestuous family, being the best-known title. Korine was a marketable wunderkind who had already gained notoriety for Larry Clark’s Kids (for which he’d written the screenplay, at the age of 18) and his first directorial effort, Gummo. It wasn’t hard for Julien Donkey-Boy to get released and noticed.

Other American efforts flew under the radar. Rick Schmidt’s Chetzemoka’s Curse (Dogme #10, 2001) is a drifting series of relationship vignettes, much of it delivered via monologue. The film is one of the few Dogme 95 titles to take the absence of a director seriously; although often credited to Schmidt, it was actually directed by him and six other people as part of a feature-film workshop. Another underseen gem was Andrew Gillis’s Security, Colorado (Dogme #24, 2001), which followed the romantic anxieties of a young record-store clerk. Intimate and beguiling, the picture was a true character study, told with a minimum of narrative ornamentation. As such, it seemed to adhere to Dogme 95’s spirit far more closely than a lot of other better-known titles.

“Dogme provided a potential blueprint and proof of concept for ultra-low-budget DV filmmaking.”

To locate the real legacy of Dogme 95, especially in the U.S., we need to consider the larger cultural context in which it emerged. This was the age of the tech boom, when self-styled digital media prophets were predicting the death of old media and the dawn of total disruption and endless profit. By embracing video, the movement tapped into the worldwide frenzy around technology and revolution. And while someone like Lars von Trier wouldn’t have been caught dead at a tech convention, his grandiose proclamations had more than a faint echo of the language of disrupter culture. The words found in the manifesto—“Today a technological storm is raging, the result of which will be the ultimate democratization of the cinema”—would not have been out of place in the meeting rooms of many dot-com startups.

Despite a 35mm film format literally being one of the rules, on a technological level Dogme validated video as a shooting format by establishing a radical new aesthetic, thanks in large part to the influential cinematography of Dod Mantle. This wasn’t just video, it was accessible, consumer-oriented video—the same camcorders used for home movies, and a far cry from the high-end, high-definition cameras that George Lucas was using to shoot his Star Wars prequels at the time. Lucas was trying very hard to make his video images look like traditional films. The Dogme movies, by contrast, embraced the video-ness of their images, emphasizing their pixelated imperfection and slippery abstraction. Constant camera movement and the rapid-fire editing felt appropriate to the electric edges and unfussy, flat lighting of video.

The Dogme brothers’ provocations reached the highest echelons of the filmmaking pantheon. Lars von Trier wrote to Ingmar Bergman trying to convince him to make a Dogme film. He was delighted when Jean-Luc Godard asked to see The Idiots. He claimed to have written Stanley Kubrick. Vinterberg likewise approached Martin Scorsese at a film festival, and even met with Steven Spielberg in Los Angeles to convince the biggest filmmaker in the world to make a Dogme project. If you wanted to purify world cinema, having the art form’s biggest names on your side made perfect sense.

Such overtures never came to fruition. Instead, von Trier and Vinterberg wound up inspiring an entirely different—but ultimately no less influential—group of artists: independent producers, who realized that Dogme provided a potential blueprint and proof of concept for ultra-low-budget DV filmmaking. Up-and-coming producers like Jason Kliot of Blow Up Pictures and Peter Broderick of Next Wave Films cited Dogme titles (and in particular The Celebration) as demonstrating that it was possible to create successful movies with video. As Scott Macaulay of Forensic Films (which produced, among others, Korine’s Julien Donkey-Boy) put it: “[The Celebration’s] shooting and cutting style seems very fresh. The story is strong, funny, and dramatic, and there is no technological theme to the story. Only in the deepest kind of subtextual level of the film, in the decay of the social structure.”

Dogme 95’s sphere of influence

![<I>Y tu mamá también</I>, dir. Alfonso Cuarón, 2001]() Y tu mamá también, dir. Alfonso Cuarón, 2001

Y tu mamá también, dir. Alfonso Cuarón, 2001![<I>Collateral</I>, dir. Michael Mann, 2004]() Collateral, dir. Michael Mann, 2004

Collateral, dir. Michael Mann, 2004![<I>The Anniversary Party</I>, dirs. Alan Cumming & Jennifer Jason Leigh, 2001]() The Anniversary Party, dirs. Alan Cumming & Jennifer Jason Leigh, 2001

The Anniversary Party, dirs. Alan Cumming & Jennifer Jason Leigh, 2001![<I>Funny Ha Ha</I>, dir. Andrew Bujalski, 2002]() Funny Ha Ha, dir. Andrew Bujalski, 2002

Funny Ha Ha, dir. Andrew Bujalski, 2002![<I>Julien Donkey-Boy</I>, dir. Harmony Korine, 1999]() Julien Donkey-Boy, dir. Harmony Korine, 1999

Julien Donkey-Boy, dir. Harmony Korine, 1999

The new millennium saw a surge of interest in ultra-low-budget, handheld video films that seemed to emerge from real-life contexts, even if they weren’t Dogme 95 titles. The Anniversary Party (2001), directed by Alan Cumming and Jennifer Jason Leigh (who had starred in The King Is Alive), was an ensemble drama featuring well-known actors (including the two directors) playing dramatized versions of themselves. Similar films followed: Gary Winick’s Tadpole (2002), Peter Hedges’s Pieces of April (2003) and Ethan Hawke’s Chelsea Walls (2001), among others. Not long after, the so-called Mumblecore movement, made up of lo-fi, comic-romantic dramas usually featuring awkward twentysomethings, took hold of the indie art-house scene, giving rise to filmmakers such as Andrew Bujalski (Funny Ha Ha, 2002), Joe Swanberg (Hannah Takes the Stairs, 2007), Greta Gerwig and Joe Swanberg (Nights and Weekends, 2008), and Josh Safdie (The Pleasure of Being Robbed, 2008). Interestingly, with video becoming so ubiquitous in the independent world, some Mumblecore filmmakers re-embraced celluloid—but they still adhered to the lo-fi, intimate aesthetic that Dogme had helped take mainstream.

One wonders if the fetishization and commodification of extreme low budgets during this period accelerated the bifurcation of the American film industry into tiny releases on one end and massive franchise spectacles on the other. Because right at the time studio movies were drifting further toward expensive action fantasies and superhero adventures, the world of independent film—presenting an alternative vision of cinema—was racing toward micro-budgets and smaller audiences. The once-ubiquitous medium-budget comedies and dramas seemed to go extinct in American theaters. Meanwhile, digital projection, a technology that had developed slowly and spottily across the years, was consolidating. Lucas’s use of high-definition video to shoot his Star Wars prequels had led to efforts to release the films via digital projection, and the technology had finally reached a stage where it could compete with 35mm in theaters.

But the Dogme 95 aesthetic didn’t just influence small indie releases by unknowns; mainstream studio filmmakers had also taken notice. Vinterberg recalled that Alfonso Cuarón once told him Y tu mamá también (2001) was directly influenced by The Celebration. Steven Soderbergh, preparing to make his low-budget 2002 DV ensemble comedy Full Frontal, circulated his own 10-point manifesto for prospective actors, clearly inspired by Dogme 95. (“1. All sets are practical locations.… 7. Improvisation will be encouraged….”) All sorts of directors seemed to be embracing the obstructional ethos, setting for themselves new challenges that blended the technological with the artistic. Mike Figgis’s Timecode (2000) unfolded across four simultaneous quadrants, with each corner of the screen consisting of an unbroken, handheld, real-time shot.

Consider Paul Greengrass’s Bloody Sunday (2002), a startlingly immediate re-creation of the 1972 massacre in Northern Ireland. Greengrass imported the aesthetic into his Hollywood career, making action hits such as The Bourne Supremacy (2004) and The Bourne Ultimatum (2007) in a distinct visual style that eventually became so common and dominant that it earned its own, vaguely dismissive moniker: shaky cam. You can also see the influence of this new style of filmmaking on Michael Mann’s Collateral (2004) and Miami Vice (2006), which used higher-end video cameras in a style reminiscent of some of the pivotal Dogme 95 films, allowing the video to be itself and not an attempt to re-create celluloid. Soderbergh’s historical epic Che (2008) also seemed to further his experiments with this aesthetic and sensibility, particularly in the immense picture’s second part, which was a ground-level, vérité portrait of Che Guevara’s final days in Bolivia.

To be clear, none of these films are Dogme titles. Many of them are those dreaded genre movies, and would have violated most of the other commandments as well. And besides, the so-called Dogme Secretariat, which issued the certificates confirming that directors had met the Vow of Chastity, was dissolved in 2002, with only a small handful of additional titles produced afterward (the last one being 2005). The movement had long since served its purpose for individual filmmakers, in particular for those Danes who, frustrated with the direction of cinema both in their home country and abroad, sought rejuvenation and solidarity. In Denmark, Dogme became a cultural and spiritual force. Internationally, however, it became an aesthetic movement—and a genuinely transformative one at that. Its influence on the movies made all over the world in the 2000s was rarely direct but it was still seismic, maybe even existential. Cinema today exists in a world that Dogme 95 made possible.