Speaking Volumes

By Ivy Pochoda

Do the Right Thing, dir. Spike Lee, 1989

Speaking Volumes

In Spike Lee’s masterpiece Do the Right Thing, cultural prophecies resound from the sidewalk

By Ivy Pochoda

February 2, 2024

If heat were a sound, it would be music coming through an open window—someone practicing the trumpet or the piano. Or the radio from a car idling at a traffic light, windows down, a sound slow and heavy or fast and itchy. Something you can’t shake, something that weighs you down or crawls inside.

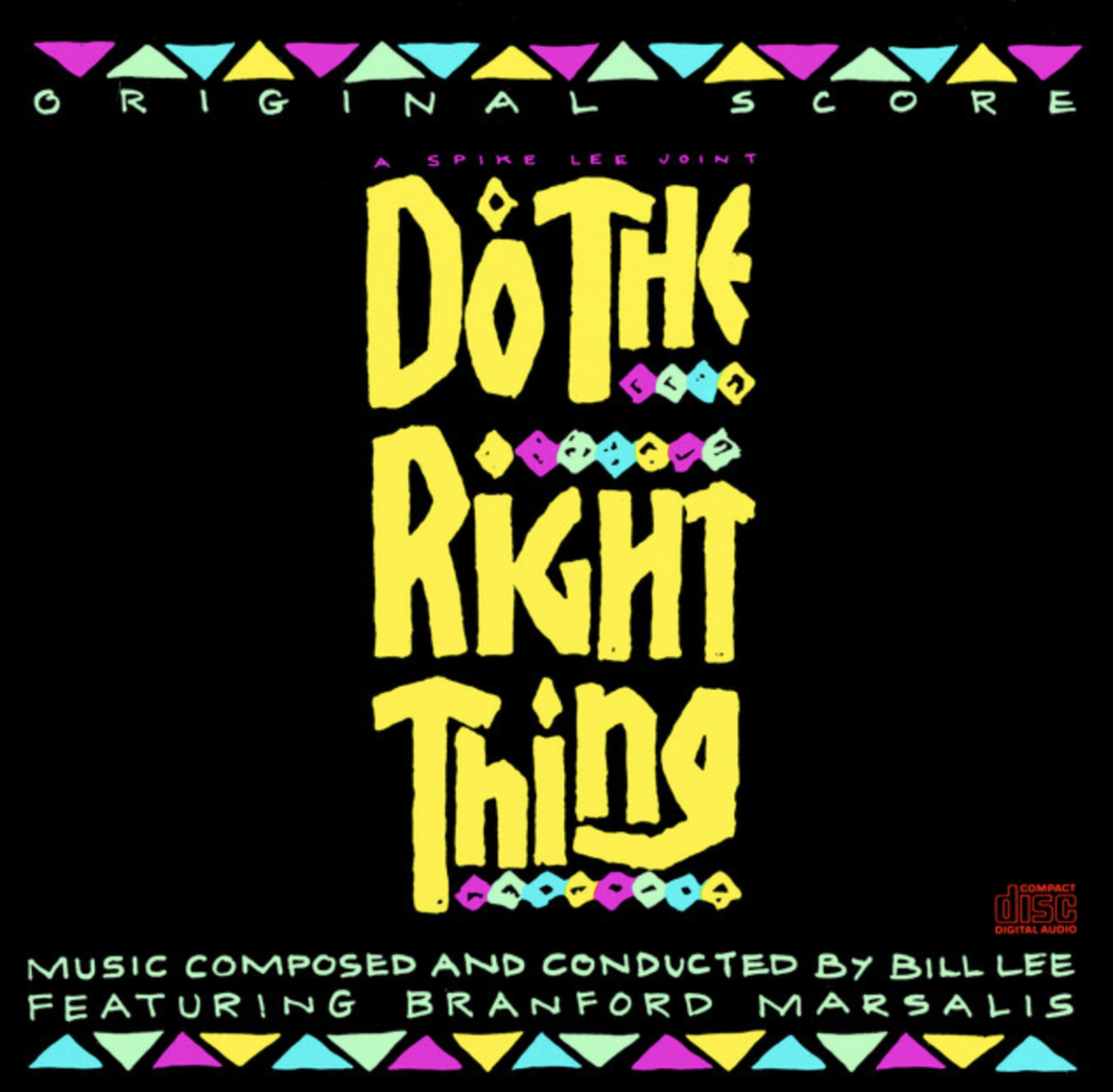

Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing is a soundscape of heat: Brooklyn DJ Mister Señor Love Daddy (Samuel L. Jackson) spinning records on the radio, music blasting from rival boom boxes, quiet jazz rippling in the background as the August day drags and the temperature soars; there are also the streetwise voices calling out in joy, jest, indignation and rage. The heat is rendered as both a visual and auditory hallucination—not only in cinematographer Ernest Dickerson’s earthy palette of rust and amber, but in the film’s instrumental score composed by Lee’s own father, Bill Lee, that rises and falls with the temperature and is now and then interrupted by the aggressive notes of Public Enemy or the upbeat tempo of “Can’t Stand It” by Steel Pulse.

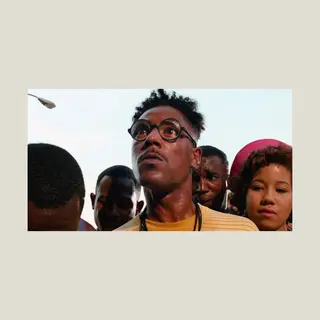

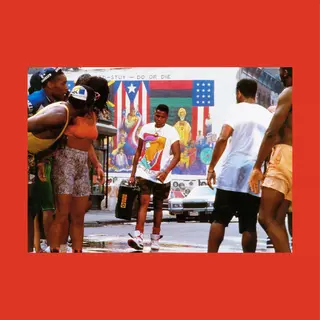

From left: Giancarlo Esposito as Buggin Out; a sidewalk scene in Do the Right Thing

These brash, overlapping voices that fill the Brooklyn block in Lee’s 1989 masterpiece serve as far more than background filler—particularly in a film celebrating Black culture in a gentrifying borough where racial tensions are, at their coolest, on a low simmer. It will be these voices that rise into a crescendo at the film’s climax as a horrific act of police violence leads to a riot that rips through the neighborhood. Together they work as chorus in the most classical sense, deployed in Lee’s film in the very way that classical Greek dramatists intended for choruses to behave—to amplify, explain and ultimately goad the action. They are lyrical and rhythmic. Their chants are woven around and through the dramatic dialogue, and by the film’s conclusion, they move from the sidelines to center stage. In traditional tragedies of the 6th century BCE, the chorus comments on the drama, providing background, setting or context, as well as hedging the audience’s sympathies. In later plays, such as those by Aeschylus, the chorus steps into the drama and becomes part of the story itself—a character all its own.

The most apparent chorus in Do the Right Thing hews more to the traditional definition. Take a look at ML (Paul Benjamin), Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison) and Sweet Dick Willie (Robin Harris), three older Black men who pass the day shooting the shit on folding chairs set out on the sidewalk, cracking wise and razzing each other. Their commentary reflects and reinforces the central themes of the film but doesn’t affect the action. They complain about the newly arrived Korean shopkeepers, who are finding success in a neighborhood that barely provides for this trio. They imagine they could take down local legend Mike Tyson. Their insults and jokes give insight into the block’s tensions and characters. But they remain on the sidelines, never really venturing into the action at hand.

While much has been made of the choral ensemble of these old-timers, little has been said about a younger quartet who soon take the stage: Punchy (Leonard Thomas), Ahmad (Steve White), Cee (Martin Lawrence) and Ella (Christa Rivers), four loudmouth twentysomething friends with nothing better to do during the heat wave than run their mouths at anyone who passes. Their chatter might seem random and at times childishly rude, but listen closely and you will hear the entire film foreshadowed in their patter.

From left: Martin Lawrence, Steve White, Christa Rivers and Leonard Thomas in Do the Right Thing

It is through them that we first encounter Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), a monolith of a man with a massive boom box who inspires fear and awe as he patrols the block playing Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” This choral quartet’s reaction to Raheem teaches us that he is to be revered and respected. “You the man, I’m just visiting,” Punchy says. “It’s your world, G,” Ahmad echoes. “For real—in a big motherfucking way,” Cee finishes.

Like Dionysus in Euripides’s The Bacchae, Radio Raheem is a new god freshly descended to Earth—in this case, late-1980s Bed-Stuy—bringing with him a new gospel. His religion is unapologetic, unyielding Black pride. Just as Dionysus was distrusted by the Theban elite upon his arrival in the city, many folks on Lee’s block dismiss Raheem and his music as way too loud and way too much. But Punchy & Co. know that acceptance and reverence are the only way forward. They bow to him, talk him up, offer him their mad respect. When they first encounter him, they yield and give way, and in doing so hint at the inevitable destruction for those who won’t.

The function of a classical chorus is performative—its presence on stage heightens emotion and reinforces atmospherics through rhythm, chanting, movement and costume. That is what Ella, Punchy, Ahmad and Cee do. They are the vibe of the street, its call and response—its strophe and antistrophe, shouting up into brownstone widows, yelling across the block. They are both real and hyperreal in talk, dress and swagger. They catch the outsize vibe of the time, loud, bright and proud in colorful, dynamic streetwear by costume designer Ruth Carter that captures the playful Afrocentric style of the moment.

Ahmad opens a fire hydrant and his friends direct the spray by shooting it through tin cans as they dance and spin through the water. They are heat and boredom embodied. They are summertime energy and its doldrums. They are the day’s highs and lows, its baseline rhythms. They are also answering Lee’s summons to be vocal and proud of their block and their heritage.

Do the Right Thing

They are the voices underscoring the rage of local loudmouth Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito) after his new Air Jordans are scuffed by a white man on a bicycle. “He did that shit on purpose,” Ahmad says, looking from the white guy on the bike to his friend. “You used to be so fine,” Ella tells Buggin Out. They are the noisemakers who get in the face of Da Mayor (Ossie Davis), the block’s wise and drunken fool, advancing their aggressive youthfulness over his old-time passive acceptance. “A bum…an old drunk zero,” Ahmad calls him.

Ultimately, it is this foursome that sets the film’s final showdown in motion—and fittingly, it’s in these scenes that they transform from sidelined characters to active participants. For nearly two hours Lee’s film has tightened the racial tensions between local pizzeria owner Sal (Danny Aiello) and his sons (John Turturro and Richard Edson), and the longtime Black residents of the Bed-Stuy community. Sal’s Famous Pizzeria is an institution, albeit a white one, in a Black neighborhood policed by white cops and recently occupied by Korean shop owners. While the core of this conflict is embodied by Sal’s only Black employee, the laissez-faire Mookie (played by Spike Lee; some have interpreted the character as a commentary on Lee’s place as a Black director in white-dominated Hollywood), it is the young choral quartet that gives texture and context to the impending clash.

The quartet bangs on Sal’s window after closing, clamoring to be fed. Sal, momentarily brimming with love for the community despite a challenging day, lets them in. They bring their noise, their musicality, their hype into the place. Their energy is a reminder that the sounds of the block are their voices, not the low-key quiet of Sal’s after a long workday. The story is their energy, their music, their excitement and anger, that will not and cannot be tamed.

“Their chatter might seem random and at times childishly rude, but listen closely and you will hear the entire film foreshadowed in their patter.”

Despite getting after-hours pizza, they jump to Radio Raheem’s defense when he appears with Buggin Out to announce their boycott of the restaurant over a lack of Black faces on Sal’s wall of fame. They immediately acknowledge the dominance of this avenging god over Sal, an interloper in their midst. They resist Sal’s demand that Raheem lower the volume on his boom box. Through this foursome’s eyes, we see that the days of tolerance and acceptance of Sal’s mild racism served alongside his slices are over. They cheerlead Raheem and Buggin Out’s rage, and their exhortations fan the flames of the discord as Sal takes a baseball bat to Radio Raheem’s boom box, starting a revolution that will take him down.

The fight between Radio Raheem and Sal spills out into the street. The chorus follows, chanting their fury. They are now part of the mob. The original four are joined by the rest of the block as the police put Raheem in a stranglehold. Like a classical chorus, they explain the action, crying out after the cops have killed Radio Raheem and removed his body from the scene:

They killed him

They killed Radio Raheem

It’s murder

They did it again

Just like Michael Stewart

Murder

Eleanor Bumpurs

Murder

Damn, man, it ain’t safe

In our own fucking neighborhood

Never was

Never will be

Spike Lee and Danny Aiello in Do the Right Thing

It would be easy enough to extend this eulogy for the dead into the modern day, adding the more recent names—Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, to name a few. And perhaps this is the first instance we were publicly urged to “say their names.” In this moment, Lee has brought us to the precipice, calling out the violence that will tragically become a precedent, marking it, decrying it, putting the world on notice.

When Raheem is dead, the chorus amplifies this very outrage, and in doing so, inadvertently goads Mookie to hurl a trash can through Sal’s window, prompting the riot which will eventually ruin the pizzeria and its owner. In the aftermath of Raheem’s death, Lee forecasts the misguided media (and public) response to the ongoing scourge of police brutality, which overlooks the death of a young Black man in favor of the ensuing riot—the response to the tragedy instead of the tragedy itself. Raheem is forgotten. The violence lives on.

At the end of Aeschylus’s Eumenides, the final play in his Oresteia cycle, the chorus is transformed from avenging Furies into the first judges of the new court established by Athena in her namesake city. Lee’s chorus undergoes a similar transformation. First, the quartet is called to action by escalating racial tensions. They are made furious and showcase their rage. Like the Eumenides, they stand in judgment over Sal and the horrific acts of police violence. As the street clears and the riot’s aftermath is revealed, one senses that the chorus will be permanently altered—no longer simply streetwise loudmouths, they are now vocal activists, crusaders for justice.

In his Poetics, Aristotle argued that Aeschylus diminished the role of the chorus by writing the performers into the action, stripping them of their removed, all-knowing power. But the evolution seems only natural in Lee’s film. There are times during a do-nothing day, for instance, when it’s cool to run your mouth, take up petty grievances, underscore the activity on the street by opening a fire hydrant or mouthing off to a white gentrifier. But then there are moments when more than talk is needed, when action is necessary and you must become the fiery, furious heart of the story, when it is necessary to step up and fight the power.

Do the Right Thing (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)

Bill Lee