Slow and Steady: Christopher Blauvelt

By Yonca Talu

Meek's Cutoff, dir. Kelly Reichardt, 2010

Slow and steady

Christopher Blauvelt’s observant cinematography

demonstrates a commanding restraint

By Yonca Talu

August 25, 2023

One of the greatest independent directors of our time, Kelly Reichardt has been collaborating with cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt for more than a decade to create visually stunning, thought-provoking films that stand as miniature portraits of past and present America. Whether they’re capturing the hardships of 19th-century Oregon Trail pioneers in Meek’s Cutoff (2010) or the trials and tribulations of modern-day Montana residents in the triptych Certain Women (2016), Reichardt and Blauvelt use expressive compositions and fluid, patient camerawork that draw us into their characters’ experiences against the backdrop of alluring Pacific Northwest landscapes. This intimate, observational approach reaches new heights in Reichardt’s latest—and most playful—work, Showing Up (2022), shot by Blauvelt and starring Reichardt regular Michelle Williams as a Portland sculptor who comes up against the chaos of everyday life while preparing for an exhibition. Fresh from wrapping up Todd Haynes’s May December (2023), the Los Angeles–based Blauvelt joined me virtually to talk about training with Harris Savides and Gus Van Sant, teaming up with Reichardt for the first time and coming into his own as a director of photography over the years.

Kelly Reichardt and Christopher Blauvelt on the set of Showing Up, 2021

I was surprised to discover that before making your way into American independent cinema, you started out in the camera department of ’90s Hollywood blockbusters like Speed and the Lethal Weapon sequels. How did you get involved with those movies?

That must look like a funny trajectory, right?

It’s unusual!

Oh, good. [Laughs] My story is that I grew up in Los Angeles, in Hollywood. My grandfather was a grip; my grandmother was a costume designer; and my dad, uncle, brother and nephew all work in the camera department. As a kid, I would visit my family on set, and I loved shooting with cameras and taking photographs. But I didn’t like school at all: It made me upset and sick, and the condescending tone of teachers turned me off. So I got interested in my own things, like skating, but they weren’t anything to create a career path with. When I was 17, my dad sort of saw the writing on the wall and said, ‘‘You better check this job out, or you’re gonna be delivering pizzas for the rest of your life!’’ [Laughter] That’s how I became a stagehand for television. It was a really great experience that encompassed all the departments: One day I’d be handling props, the next day I’d be doing lighting, the next day I’d be building sets, etc.

How long did you do that job?

I did it for about a year and a half, until my dad told me, ‘‘You should come to the film-studio lots.’’ All the films shooting on the lot got their loaded camera magazines from the same hub. My dad introduced me to some people there, and they were like, ‘‘Yeah, get in here and load.’’ So I got a fast track to learning how to load [film stock into cameras], and I was loading for these giant hundreds-of-million-dollar movies, like the Lethal Weapon series and Speed. I really enjoyed it, but I was just a small piece of the machinery—there were tons of cameras, camera assistants and operators. It was a very practical job, and I wasn’t fulfilled in a creative way.

Everything changed for me when I met Harris Savides [the late cinematographer known for his collaborations with Gus Van Sant, David Fincher and Noah Baumbach, among others]. I was still a loader when I met him—I was very low in the hierarchy—and he gradually let me move up into each position.

Gerry, dir. Gus Van Sant, 2002

What did Harris Savides impart to you?

What Harris brought me was an appreciation for cinema as an art form. When I started working with him, he gave me amazing movie recommendations: We’d watch [Yasujirō] Ozu films together, and he told me who [Michelangelo] Antonioni was. I didn’t have an education in film; I only had hands-on experience. But Harris opened up the world for me in that way, and I sort of got the schooling I had always wished for, thanks to him.

How did your collaboration develop over the years?

After we collaborated on some commercials and David Fincher’s The Game [1997], Harris brought me on as a first assistant camera on Gus Van Sant’s Gerry [2002], which was a huge one for me. I mean, I used to live in a house in the Valley with a bunch of punk rockers, and I would force them to watch [Van Sant’s] Drugstore Cowboy [1989] and My Own Private Idaho [1991]. Those were my favorite films. I remember Harris and I were on a job together, and he was telling me that he’d been hanging out with Gus. He knew that I would light up every time this came up because I just wanted to know what Gus was like. Then he said, ‘‘Gus and I are going to make a movie. But it’s really low-budget; there’s no money. You want to do it with me?’’ And I was like, ‘‘Yes!’’ There was no question in my mind. I thought, Okay, now I’m working with the people making the films that I like; this is my taste. Even to this day, it’s the best life I could ever hope for. I work on movies that I love, and it’s crazy to even say that out loud, but it’s the truth. You know, I just shot a movie for Todd Haynes. He’s one of my favorite filmmakers; so is Kelly Reichardt. I’m very grateful.

Let’s talk about Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff, which was your breakthrough feature as a cinematographer. I’ve read that you took over that film from another DP shortly after it began production in the Oregon desert. What was it like to jump into such an ambitious project without any preparation, and how did you and Kelly Reichardt collaborate on set? Did you mostly focus on executing her vision, or were you able to bring new ideas to the table?

That’s a really good question; I’ll start from the beginning. I’d been trying to cut my teeth as a DP by shooting micro-budget, kind of trashy movies. I knew that Kelly was making Meek’s Cutoff because the camera assistant on the film, Stephen MacDougall, was my assistant at the time, and I’d worked with the producer Neil Kopp on Gus’s Paranoid Park [2007]. I got a call from Steve, who told me that Kelly and her DP weren’t getting along and that she was up in arms, like, ‘‘Somebody help me. Just give me someone who’ll be compatible with me.’’ I hadn’t done much as a cinematographer, so it was hard to imagine that I’d be the one. But Steve and Neil threw my name in there and I said, ‘‘Let’s go for it.’’

So you hadn’t even met Kelly Reichardt before?

No! I read the script on the plane—we were shooting the following morning—and met Kelly when I landed. It was a four-hour ride to get to the deep desert, and I hadn’t slept more than an hour. In the car, Kelly broke down to me her aesthetic, which was very minimal and observational. One of the things she said was that she wasn’t happy with the tools they’d been using to move the camera [to follow the settler characters around in the desert]. The movement was too rough and not as motivated as she’d like it to be, so she didn’t want to move the camera at all anymore. I thought, Okay, but my instinct was that it’d be weird to have static shots of people moving.

The first shot of the day was the character of Meek coming out of his tent and stretching. Then there was a shot of him walking over to a vista and looking out. Kelly was doing costuming three miles away and had left me to set up the frame. The first thing I did was lay down a dolly track, which the crew really supported me in. My idea was to combine those shots of Meek: I would start at the first one and dolly over to the second, and if Kelly didn’t like that, Meek would walk out of frame and I’d slide over to his second position. I was just getting to know Kelly and didn’t want to get fired. But I still wanted to pitch my idea to her because I understood her problem with movement and felt like I could show her something more along the lines of her vision. Kelly looked at the dolly track and was like, ‘‘What the fuck is going on?’’ And I said, ‘‘Let me just show you!’’ I showed it to her, she loved it and it was game on from then on. We collaborated on that immediately, and she’s always let me have a voice.

While shooting Meek’s Cutoff, did you draw at all on your experience working as Harris Savides’s assistant on Gerry, which also centers on characters lost in the desert and employs long takes and a stripped-down aesthetic?

Yeah, absolutely. What I did on Meek’s Cutoff was drawn almost directly from Gerry, especially in the beginning, and I had confidence in the long dolly tracks because of my experience on that film. Those times I spent with Harris are ingrained in my body and mind, and I think about him every day. He’s a big part of how I view the world and filmmaking and even just life. I call on him all the time for insights when I’m shooting. It could be as simple as, What would Harris do? And I think, Oh, yeah, I remember he did this.

What was most unique about Harris Savides’s approach?

Harris’s approach was unique because of its simplicity. A lot of DPs overcomplicate things with too much equipment and too many ideas, but Harris was so good at showing restraint. That’s been a great guiding principle for me in my collaboration with Kelly. I like to say that the films we make are thoughtful, because we really think about what we’re doing and how and why we’re doing it. If you ask yourself those kinds of simple, basic questions, you’ll realize that you start to pull back, not do too much and let it be. Of course, there’s a time and a place for everything, and the choices that a cinematographer makes should be bespoke for each script. But as a general rule, I always think to myself, What are we trying to say with this scene? Is the camera motivated by something, and if not, why? It’s about trying to give purpose to what you’re doing, and if you do that most of the time, I believe the films come across as a lot more pure, authentic and thoughtful.

Night Moves [2013] marked your first time going into preproduction with Kelly Reichardt, who’s known for meticulously previsualizing her scripts through references. What was that process like on this film, which stands out as her darkest, most anxious work? How consciously did you borrow from the psychological-thriller genre to create its look and mood?

There are definitely elements of that genre in Night Moves, as you’ve noticed and a lot of people do. Kelly wanted to have those sprinkled in there, but she’ll never say it out loud. You’d never hear her say, ‘‘Oh, I’m going to make a film noir.’’ That might be part of her references, but she pulls from a lot of things, including movies, photographs and paintings. She’s very studious and does more research than anyone I know. Doing prep with her is a very intense, immersive and fulfilling process. When we’re shot-listing, there’s always a record playing that’s relevant for tone, or a movie is cued up for us to watch scenes from. Ideas can happen in such an environment.

What sources were you working with on Night Moves?

For Night Moves, all of Kelly’s reference material was very dark. It was a film that wanted to have an ominous tone because of the danger that the characters were living in. But it was also supposed to be just an observation of them as they set out to do something pretty extraordinary and drastic [i.e., blowing up a dam]. One of our references was the documentary If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front [2011], about members of the ELF who went to jail for burning up a forestry business and whose actions fell under terrorism. We also found a guy in Oregon who’d blown some shit up and had missing fingers. He showed us the process of making what the characters make in the film [i.e., a bomb], but I probably shouldn’t say too much! [Laughter]

Night Moves was also Kelly Reichardt’s first film shot on digital.

Yes. We decided to shoot digital for budgetary reasons but also because a lot of the movie takes place at night. It was a challenge for me to get Kelly to sign onto it because she’s so visually acute—she can really tell the difference between digital and film. I started by doing some tests, like filming a girl in a parking lot with a chart and different lenses and filters. But when I showed that to Kelly, she was like, ‘‘You can’t do this to me. It’s awful.’’ And I thought, Oh, no, I’m blowing it. That was a huge lesson for me in terms of learning how to test. As Harris used to say when we’d do tests together, ‘‘We’re not shooting a fucking chart.’’ It’s about not letting the technical get in the way of the art form, and I tell the kids that I work with sometimes, ‘‘Make sure you’re putting into the test as many elements of your film—costumes, production design, an actual location, etc.’’ There’s a real discipline to testing, and after doing more of that on Night Moves, I was able to get Kelly to really like the image. I got her to feel like it was film again, which to me was a big accomplishment.

From left: Lily Gladstone and Kristen Stewart in Certain Women, dir. Kelly Reichardt, 2016

What prompted you and Kelly Reichardt to go back to 16mm on her following film, the Montana-set Certain Women?

Certain Women actually started in digital. We were doing our prep in Montana. There was snow everywhere and the sky was bright blue. We did some tests but weren’t satisfied, because the clipping of digital doesn’t roll off the highlights as much as film. We both thought we couldn’t do this on digital, and Kelly was the one who finally said, ‘‘Let’s talk to the producers Neil [Kopp] and Anish [Savjani] and get a film camera here.’’ But by the time we were shooting, there was no more snow! [Laughs]

Ahead of Certain Women, you and Kelly Reichardt spent a lot of time in the ranch that serves as one of the film’s key locations. How did that inform the way you shot the story of the ranch hand played by Lily Gladstone?

That ranch was owned by a wonderful couple, Lynn and John Melvin. John was allergic to horses, so it was Lynn who took care of them every day. We went there as curious observers and asked her if she could show us her routine. There were about 23 horses, so this woman had a job; it was no joke. She got up every morning before sunrise, when it was freezing cold, and did everything that we watch Lily Gladstone’s character do in Certain Women. The dog, Rowdy, was also hers, and he would chase her four-wheeler like in the movie. All of that stuff happened, so we were just cataloging what was going on and figuring out in our schedule how to capture it.

It seems like your preparation with Kelly Reichardt always involves observing real people as inspiration for the characters. Most recently, for Showing Up, you documented the processes of two artists: Michelle Segre, whose work is featured in the film, and Jessica Jackson Hutchins.

Yes. We always try to get experience with actual humans, and that was our prep for Showing Up. Kelly loved Michelle Segre’s work, which was an inspiration for us on First Cow [2019]. When the idea for Showing Up was just a seedling in her and [her writing partner] Jonathan Raymond’s heads, Kelly approached Michelle about spending a day and shooting with her in her studio in New York. Michelle agreed, so we got a 16mm camera and filmed her making her art. We did the same with Jessica Jackson Hutchins in Long Beach, California. Those informed the way we shot Michelle Williams’s character, Lizzy, in Showing Up. We let her live in her environment and observed her quietly as she made her sculptures [whose actual creator is artist Cynthia Lahti].

How did you shoot the opening title sequence of Showing Up, which lets us gaze at Lizzy’s figure studies on the wall in a single uninterrupted take? I love how every time you pan and land on a new drawing, we can see you zoom in and out in search of the right frame, the roughness of which echoes the film’s subject matter of sculpture.

Absolutely. Kelly wanted the film to have a homemade quality and feel simpatico with Lizzy’s style of art, which is a little imperfect. When we shot the title sequence, I was repositioning the camera, but Kelly left it open so that I didn’t know until I saw the cut that she was going to use those reframes instead of just the locked-off parts, which is really cool. But then there were scenes like the zoom that begins on the street and goes up to the window of [Hong Chau’s character] Jo’s studio. It hurt my soul not to do a nice, nonexistent zoom there, but Kelly kept saying, ‘‘Not rough enough!’’ She grabbed the camera and was like, ‘‘Come on!’’ [Laughs] So we finally did one that’s a bit more rough and gradually finds itself.

Jesse Eisenberg in Night Moves, dir. Kelly Reichardt, 2013

That reminds me of the fact that although Kelly Reichardt is very keen on doing shot lists, she asks you to relinquish them on set and be open to improvisation.

That happens every time! I’ll tell you what—the paper I keep in my pocket, which is the shot list, helps me and my team. If I need a dolly track or jib arm, there are notes on the shot list attached to those things. Sometimes I’ll peek at it and remind Kelly of something that I made a note of, and she’ll be like, ‘‘Oh, that’s a great idea.’’ But other times, when she sees me with it out, she’ll say, ‘‘Put it away! I don’t want that to be our guiding principle.’’ The shot list is an exercise for us to make sure we know what we’re talking about on every level. It’s a blueprint that’s built into our heads, and when it’s time to go, it makes us free because it’s there.

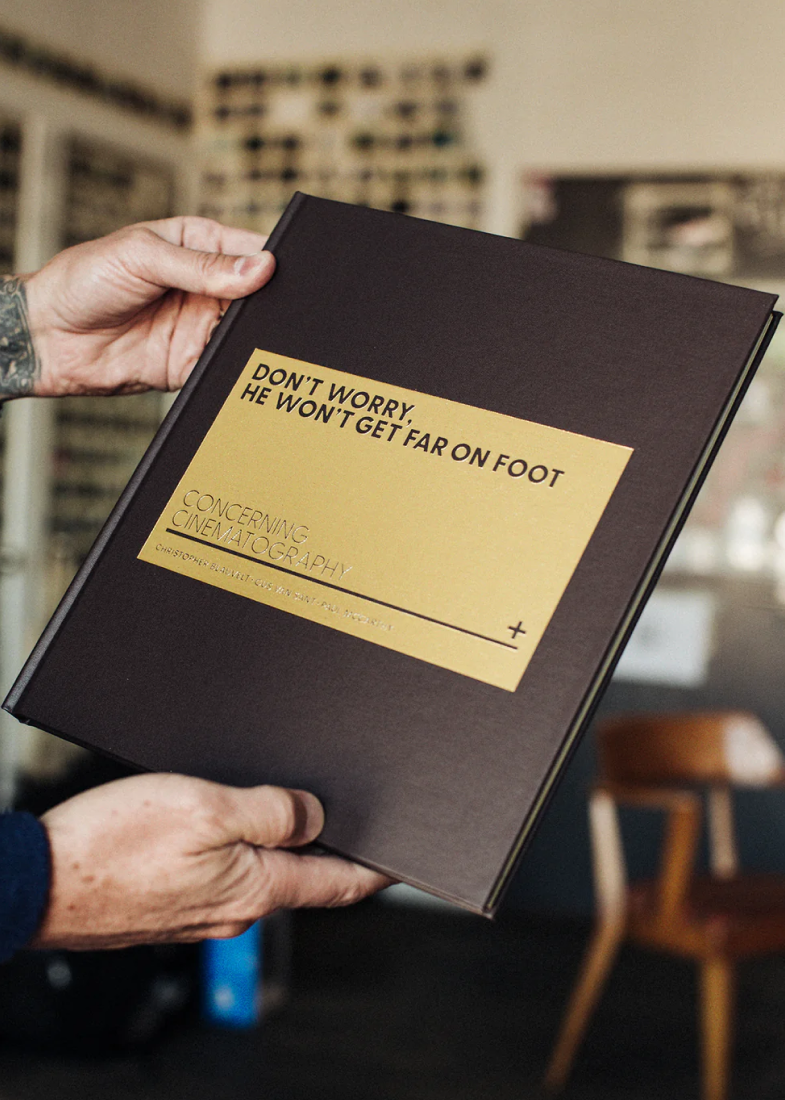

What about when you shot Gus Van Sant’s Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot [2018]? How much freedom did he give you in terms of operating the camera?

Gus doesn’t like to have a shot list—everything needs to be natural. When he blocks a scene, he doesn’t even want the camera to be there. He’s a true artist who does not follow any formulas or norms that I know of. I recently asked him why he remade Hitchcock’s Psycho shot for shot [in 1998], and he replied, ‘‘I just wanted to see what happened.’’ [Laughter] He’s like a little kid, so free that he’s willing to fail because he wants to try something, and that’s what’s beautiful about him. He’s just an anomaly on the planet, I think.

In Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, there are scenes in which you seem to be intuitively zooming in on actors’ faces and capturing their reactions in the moment.

When that movie came about, Gus was very much into D.A. Pennebaker and the Maysles brothers’ documentary style [i.e., cinéma vérité]. He wanted to have the freedom of zeroing in on a detail, which is why we used zoom lenses. In the beginning he said to me, ‘‘Chris, I want to look at everything.’’ I said, ‘‘Could you be more specific?’’ And he was like, ‘‘Read my lips. Fucking everything.’’ He really wanted to see everything, from iPhones to Blackmagic cameras to Super 8 to VHS, etc. I reached out to my friends Rick [Charnoski] and [Coan] ‘‘Buddy’’ [Nichols], who made a bunch of skate documentaries with their production company, Six Stair. They had tons of 8mm film, Hi8 [8mm video] and VHS. So I put together a whole reel with those and screened it for Gus in the theater. That’s how we checked off things like VHS, which looked amazing but would’ve leaned too much into nostalgia. We finally settled on the Arri Alexa Mini in combination with the Pennebaker zoom lenses, but we shot in Super 16 mode, so the resolution was lower than HD. The distributor, Amazon Studios, freaked out because they were bragging about all their movies being shot in 4K and this was of lesser quality than your phone. [Laughs] But I really love how the film looks. It has a noisy texture because of the low resolution, and we also integrated film grain in there.

Book by Christopher Blauvelt with Gus Van Sant, Paul McCarthy and Stephen Marsh

How did you feel about becoming Gus Van Sant’s cinematographer after years of moving up the ranks by his and Harris Savides’s side?

It’s so huge that it’s even hard to articulate. When Gus offered me Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, I immediately thought of Harris because he would have been the one to shoot it had he been alive. I was grateful, honored and shocked; there were so many things going through my head. It all happened while my wife and I were visiting her parents in Arizona. I went out for a walk in the desert, the sun was setting and there were plants, birds and coyotes. It was such an amazing, surreal place, and I thought to myself, I have to do something to honor where I’m at and my privilege in this film. When Harris and I worked together, we would draw lighting diagrams and take Polaroids, which we’d then compile into little books. So I decided to make a book about Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot. My assistant Jake Magee, who was my loader at the time, is a really good illustrator, and the two of us spent a lot of time on that movie making beautiful diagrams and taking Polaroids. The book that came out is called Concerning Cinematography + Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot. It’s dedicated to Harris of course, and it was one way for me to give back to him or at least honor his spirit.