Performance Anxiety

By Adam Nayman

All That Jazz, dir. Bob Fosse, 1979

Performance Anxiety

The soulful narcissism of All That Jazz, Bob Fosse’s self-reflexive showbiz masterpiece

By Adam Nayman

April 12, 2024

“Oh, boy, do I hate show business,” carps Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) midway through All That Jazz (1979). Joe is an award-winning theater director and choreographer who’s never met a challenge he couldn’t complain about; his girlfriend Kate (Ann Reinking) is a dancer who’s heard this particular song-and-dance routine before. She’s in no mood for an encore. “Joe, you love show business,” Kate says acidly. “That’s right,” he deadpans. “I love show business. I’ll go either way.”

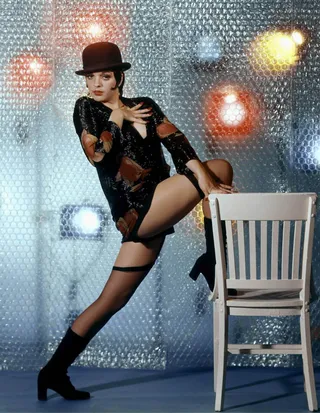

From left: Roy Scheider as Joe Gideon; Erzsebet Foldi and Ann Reinking in action

If ambivalence can be virtuosic, then the ability to seemingly lean in two directions at once—on his feet and in his art—is Joe Gideon’s specialty. It’s a legacy that he shares with his creator. Of all the signature filmmakers of the New Hollywood, Bob Fosse may have been the most mercurial as well as the most tragically self-divided; Scheider’s performance in the director’s fourth and penultimate feature transcends impersonation for something like inhabitation. A notorious workaholic who revolutionized both Broadway stagecraft and cinematic storytelling while piling up awards in both mediums, Fosse earned notoriety as a seducer yet spent most of his career in a passionate and dysfunctional love affair with his own talent.

Fosse’s personal and professional struggles have been well documented, both in Sam Wasson’s 2013 biography Fosse and the 2019 F/X series Fosse/Verdon, both filled with pungent, tragicomic vignettes testifying to their subject’s mix of narcissism and self-loathing. It’s been suggested that Fosse’s great theme was the ravages of fame, but to be truly precise what he was really interested in was the link between showmanship and spiritual decay. For Fosse, show business wasn’t just love-it-or-hate-it, or even take-it-or-leave-it: It was a matter of life and death.

With the possible exception of his 1972 staging of Stephen Schwartz’s satirical folk musical Pippin—which ends with the protagonist forced to choose between a life of obscurity and spectacular public self-immolation—none of Fosse’s productions distill his ambivalence as potently as All That Jazz. The film was co-written by Fosse and Robert Alan Aurthur in homage to the metafictional self-reflection of Federico Fellini’s 8½, and like Fellini’s classic, All That Jazz is the work of an artist with nothing to hide, draping a thin but tactile veil of fiction (and fantasy) over a naked, scathing self-portrait.

“The genius of All That Jazz is that it doesn’t believe in innocence even as it searches for grace.”

Deathbed spectacle in All That Jazz

A quick study who completed his film debut, Sweet Charity, in 1969 only to topple Francis Ford Coppola for the Best Director Oscar four years later with Cabaret (1972), Fosse was seemingly gifted with an innate film sense. The same knack for fusing physical and psychological expression in his stage choreography eventually carried over into the cinematic medium. Where previous masters of movie musicals had either deployed agile camera movements and angles in order to transform performers into graphic elements in a larger pattern (as per Busby Berkeley) or else subjugated themselves (and their cameras) to shooting beneath a static proscenium, Fosse forged a middle path. Beginning with Cabaret, his musical numbers were almost cubist, observing bodies in motion from multiple perspectives and syncing them through restless but pinpoint-precise editing.

What links the slinky burlesque numbers of Cabaret to the smoky nightclub stand-up routines in Fosse’s Lenny Bruce biopic, Lenny (1974), is the uncanny sensation of being simultaneously on- and offstage. If (to paraphrase Joel Grey’s demonic Cabaret MC) life under the lights is beautiful, it’s also sweatily grotesque, exhausting and exhilarating, voyeuristic and paranoid.

The implication as All That Jazz opens is that Joe Gideon is a peerless conveyer of such contradictory sensations, and also that every aspiring performer in New York would kill themselves to work with him. In the ecstatically executed prologue, we see dozens of dancers—lithe young performers whose cosmopolitanism is a microcosm of the city around them—shuffling across a rehearsal stage en masse through steps whose complexity is only part of the equation. What Joe is looking for—sometimes frowning distantly from a theater seat, sometimes scrutinizing the hopefuls eye to eye and chest to chest—is the special, ineffable quality that transcends competence (and talent). Even if we’re not specifically seeing the action from Joe’s point of view, the editing, by Alan Heim, puts us inside his head, effectively turning us into our own subjective perfectionists—and, as the herd gradually thins to a few lanky and suggestible ingenues, potential predators as well. In Stanley Donen’s mostly misbegotten 1974 musical adaptation of The Little Prince, Fosse made a wry, sibilant turn as a self-described “snake in the grass”—a joke on his own poisonous reputation as a seducer. All That Jazz isn’t shy on this point, painting Joe as an opportunistic ladies’ man peddling a sort of lascivious quid pro quo. “Fuck him, he never picks me,” complains one disappointed hopeful after she’s passed over. “Honey, I did fuck him and he never picks me either,” replies her similarly fed-up friend.

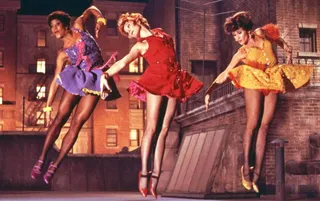

From left: Cabaret, dir. Bob Fosse, 1972; Lenny, dir. Bob Fosse, 1974

The musical Joe is casting for is a bicoastal picaresque called NY/LA, whose hot-and-heavy contents satirize the controversial choreography of Chicago as surely as the movie he’s simultaneously editing—titled The Stand-Up—is a stand-in for Lenny. Circa 1979 Fosse would have counted on audiences recognizing these reference points, but even if a lot of the comedy in All That Jazz is inside baseball, its contents are still raw to the touch. We follow Joe as he pinballs between projects, driving himself further and further into exhaustion, much to the chagrin of his collaborators and an inner circle of women. The latter includes not only Kate, but his ex-wife, Audrey (Leland Palmer as a stand-in for Gwen Verdon), and preteen daughter, Michelle (Erzsebet Foldi), and their collective exasperation with his bad habits—pretty much each of the seven deadly sins—is tinged with a mixture of love, forgiveness and resignation.

These feelings are expressed in dramatic scenes, whose scabrous, profane realism feels indebted to the films of John Cassavetes, as well as in musical numbers dredged up from Joe’s drug-addled subconscious. Convalescing in his hospital bed after a severe attack of angina, he begins to hallucinate a series of production numbers, with him as the director—an auteur presiding over his own increasingly terminal prognosis, ensuring that loved ones and rivals alike hit their marks.

To call All That Jazz morbid is an understatement; it’s one of the most exquisitely fatalistic American movies ever made, featuring no less than an ethereal, pre-superstardom Jessica Lange as a statuesque incarnation of the Angel of Death. In one conceptual coup among many, Lange’s Angelique, who exists only in fantasy sequences, is just as drawn to Joe’s masochistic devilry as the flesh-and-blood women in his life; after he confesses his vices, the Angel of Death concedes they’re a turn on. Linking Joe’s appetite for earthly pleasures and his death drive, the Angelique interludes have a certain poisonous poetry, and as Joe’s condition worsens to the point of requiring bypass surgery, Fosse plunges deeper into symbolism. Instead of figurative “interiority,” All That Jazz sets its showstopping climax inside its protagonist as he’s lying in the hospital: He imagines the inside of his body as a shimmering, impressionistic discotheque featuring dancers in bodysuits bedecked with images of arteries and ventricles. Joe’s farewell number, “Bye Bye Life”—sung by Scheider as a duet with the great Ben Vereen—is superficially unsentimental bordering on cynical (“hello, emptiness / I feel like I could die”), but the implication of the staging is that at the moment of truth, Joe Gideon’s heart is not just full but standing room only.

From left: Sweet Charity, dir. Bob Fosse, 1969; Liza Minnelli as Sally Bowles in Cabaret

No doubt Fosse was meditating on his own potential demise when he conceived the climax of All That Jazz, which may not have actually been his valedictory movie but still ends up getting in the last word about its maker—far more so than 1983’s dazzling but exploitative Dorothy Stratten biopic, Star 80. In that film Fosse got his signals crossed trying to memorialize an innocent victim of a pitiless, cutthroat industry; the genius of All That Jazz is that it doesn’t believe in innocence even as it searches for grace. The film concludes with two close-ups, each startling and terrifying in its way: a slow push-in on Joe staring down the camera behind mascara-ringed eyes, and a shock cut to a transparent body bag being zipped over his head, his eyes closed forever. Unwilling to choose between extremes—pain or pleasure, success or failure, love or hate—Fosse ends All That Jazz by having it both ways at once. After so deftly hypnotizing our gaze, this gloriously life-affirming, exquisitely death-tinged masterpiece ends by staring back at us, tenderly and defiantly, with eyes wide shut.