One Dog Goes One Way

By Zadie Smith

Goodfellas, dir. Martin Scorsese, 1990

One Dog Goes One Way

What Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas teaches us about closing our eyes to violence

By Zadie Smith

July 4, 2025

It’s not very original to claim Goodfellas (1990) as a favorite movie, but it came out during a formative moment in my life—I was 15—and had a profound effect on the way I tend to think about things. The pivotal scene, to my mind, is the one where the short-tempered sociopath Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) takes young mob initiate Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) and Mafia stalwart Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro) to Tommy’s mother’s house. It comes 54 minutes in, and is bookended by two bloody acts of violence, though I suppose most scenes in Goodfellas might be described that way. Personally, I can’t stand to watch violence, so there’s about an eighth of the film I’ve never really seen. I am aware that Tommy has just shot gangster Billy Batts (Frank Vincent) in Henry’s nightclub, but I only remove my hands from my eyes at the point when Liotta, Pesci and De Niro are wrapping the body in tablecloths. After which, De Niro and Liotta immediately begin fretting about what to do (“This is fucking bad”). But it’s Pesci who seems the most discombobulated. Which makes sense: He’s the killer. And for a moment—before he speaks—you can permit yourself the pleasant delusion that Tommy DeVito is a participant, however tenuously, in what we civilians fondly call “the social contract.” That he’s about to say something like, “What have I done?” Instead, he looks over at Henry Hill with apology in his eyes and says: “I didn’t wanna get blood on your floor.” This is where my pivotal scene begins—with Liotta’s reaction to that. He doesn’t say anything. He just meets Pesci’s beseeching gaze with a strange look of his own: a sort of dazed, underwater amazement, as if to say: This guy’s from another planet.

![]()

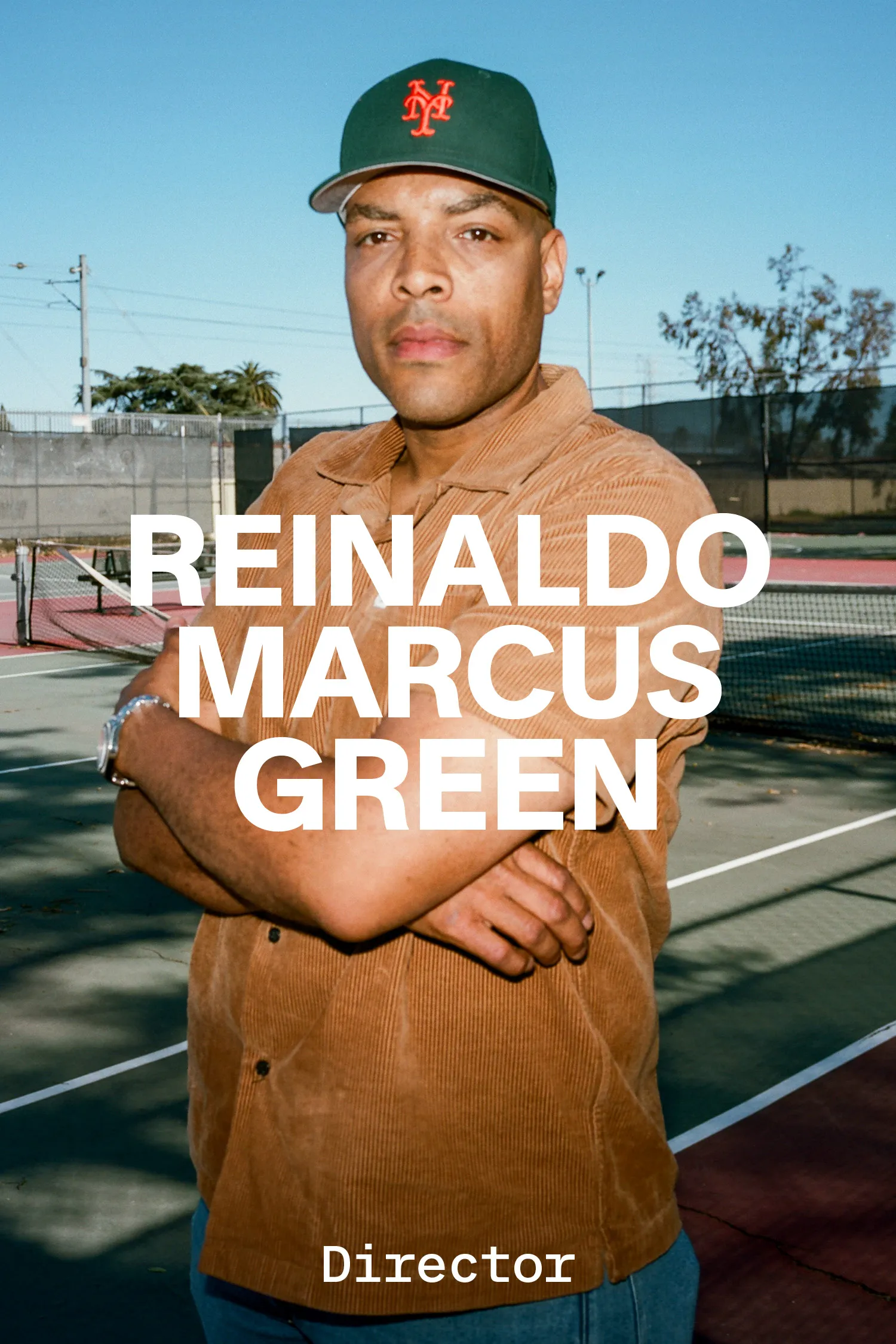

From left: Ray Liotta, Robert De Niro and Catherine Scorsese

![]()

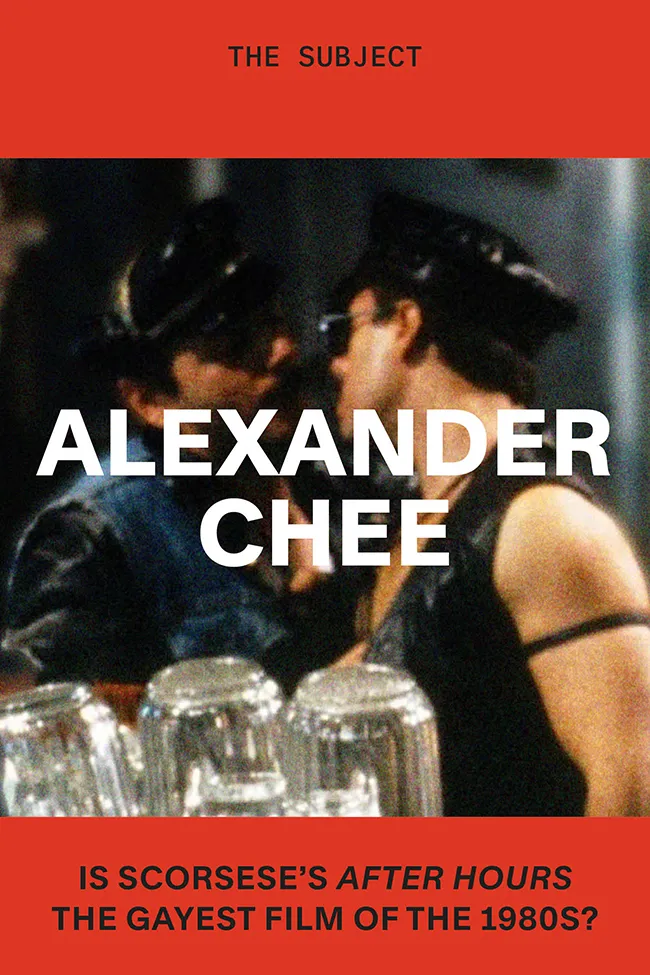

From left: Frank Adonis, Joe Pesci, Robert De Niro and Ray Liotta

“Any kind of behavior is possible if human beings find a financial advantage in it.”

He’s right about that. We’re in the world of the wiseguy, a subterranean stratum of reality wherein breaking the Sixth Commandment is no biggie, but getting blood on the furnishings offends the rules of hospitality. Meanwhile, the soundtrack swells with the song “Atlantis,” Donovan’s 1968 trippy ode to a region deep under the sea, an alternative universe, far below the world we think we know.… Henry’s induction into this netherworld is of course the subject of Goodfellas from the get-go: “As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.” But 54 minutes in is when he truly goes under.

So now there’s a body in the trunk and they’ve got no tools and no way to bury it. Off they drive to Tommy’s mother’s house, to pick up a shovel. But just as they’re creeping into the kitchen, Tommy’s mother (famously played by Scorsese’s own mother, Catherine) hears them, puts the lights on and insists on fixing the boys a plate like any good Italian nonna. Tommy’s covered in blood, Jimmy looks grim, Henry’s silent. It’s the middle of the night. Really couldn’t be any clearer that these three are wiseguys, freshly arrived from their underworld into this suburban kitchen somewhere in Queens. But Tommy’s mother—like so many of us—only sees what she wants to see. Her son has been “working nights.” He’s hit a deer. He only wants to borrow a giant kitchen knife to cut off the hoof. At any moment, of course, she could step outside to check on the existence of this supposed deer caught in the grille of a Pontiac. She could put a little pressure on Henry, who sits shiftily at the table, nervous, as if they are all about to be rumbled. But Liotta’s Henry needn’t worry. His silence is noted—“You don’t talk too much”—but there will be no interrogation. Instead, a joke:

Mother: When we were kids, the Comparis used to visit one another. And there was this man, he would never talk. He would just sit there all night and not say a word. So they said to him, “What’s the matter, Compari? Don’t you talk? Don’t you say anything?” He says, “What am I gonna say, that my wife two-times me?” So she says to him, “Shut up. You’re always talking.” [Laughter round the table]

Mother: But in Italian, it sounds much nicer, you know.

Tommy: “Cornuto contento.”

Mother: That’s it.

Jimmy: What’s that mean?

Tommy: It means he’s content to be a jerk. He doesn’t care who knows it.

Civilians are “content.” We’re jerks like that. We only see what we want to see. More often than not we’d rather not see any pain. Some of us even cover our eyes during the violent parts of movies. We’re content to live in this world of happiness and horror, kindness and brutality, our living hell and our paradise on Earth—as long as we can convince ourselves that the realms of contentment and pain are entirely separate. Chekhov explains all this beautifully:

It’s a case of general hypnotism. There ought to be behind the door of every happy, contented man someone standing with a hammer continually reminding him with a tap that there are unhappy people; that however happy he may be, life will show him her claws sooner or later, trouble will come for him—disease, poverty, losses, and no one will see or hear, just as now he neither sees nor hears others. But there is no man with a hammer; the happy man lives at his ease, and trivial daily cares faintly agitate him like the wind in the aspen-tree—and all goes well.

At the kitchen table in Queens, all goes well. The food is good, the mood is jovial, and Tommy’s mother has been occupying herself making art:

Mother: Did Tom ever tell you about my painting?

Jimmy: No!

Mother: Look at this.

Jimmy: It’s beautiful.

Tommy: I like this one: One dog goes one way and the other dog goes the other way.

Mother: One is going east and the other is going west. So what.

Tommy: And this guy is saying, “Whaddya want from me?”

Guy’s got a nice head of white hair. Look how beautiful the dog—it looks the same.

Jimmy: Looks like somebody we know. [Jimmy and Tommy laugh]

Tommy: Me without the beard. No! It’s him! [More laughter]

Tommy: It’s him!

“Goodfellas is about that coexistence: the story of one world hiding and disclosing another.”

They’re right: The guy in the painting looks like Billy Batts. And as they laugh, the camera pans away, to the window, and we can now see the black Pontiac—it’s right there—and we can hear “him.” The tap-tap-tapping of an unhappy man in the trunk of a car. The suffering Billy Batts, whom no one sees or hears, just as he can neither see nor hear others….

To me, Goodfellas is one of the great cinematic portraits of what I want to call radical alterity. The experience of Billy Batts in that trunk is so radically different, so impossible to imagine from the perspective of the kitchen table, that it doesn’t seem like the two things can possibly be happening at the same time. How can both these versions of experience be real? How can such suffering and contentment coexist? Goodfellas is about that coexistence: the story of one world hiding and disclosing another. At first the idea seems comforting. Because the wiseguy is so obviously “other”: He breaks all the rules, lives in the shadows, replaces our noble institutions with corrupt versions of his own, and can kill a man without a second thought. The purest of capitalists, he doesn’t bother with even the pretense of democratic guardrails. He is pure covetousness and cruelty, and we are not him. But Goodfellas isn’t only about wiseguys: It’s also about us. This film comprehends that the sociopathic disassociation commonly practiced by the wiseguy is, in fact, not wholly unknown to the civilian who can sometimes prove herself equally capable of contentment as others suffer around her. It’s not that difficult, this Chekhovian, water-tight self-delusion. All you have to do is never ask where the money came from. You just don’t wonder whose diamonds you’re wearing, or how come you always get given the best table at the restaurant. If your son comes home at 2:00 a.m. covered in blood and says he hit a deer, well, then, okay: He hit a deer. No further questions. All you have to do is look in the opposite direction. One dog goes one way and the other dog goes the other way. It’s a case of general hypnotism, and this hypnotic movie knows that any kind of behavior is possible if human beings find a financial advantage in it. Yes, in the pursuit of the American dream, pretty much anyone can be othered to the point of nonexistence. Pure capitalism means there’s always someone somewhere bleeding out. At least wiseguys know that. But if anybody tries to make one of us civilians pop the trunk and take a good hard look at an unhappy man? Then you’ll hear the voice of the secret gangster within: Whaddya want from me?