Mrs. Robinson's Angst

By Philip Gefter

The Graduate, dir. Mike Nichols, 1967

Mrs. Robinson’s Angst

The feminist subplot of Mike Nichols’s seminal coming-of-age film The Graduate

By Philip Gefter

February 23, 2023

The Graduate was considered a minor novel when it was published in 1963. Its author, Charles Webb, not much older than his 20-year-old protagonist, wrote the book soon after graduating from college and returning home to the suburban paradise of his upbringing in wealthy Pasadena, California. This early example of autofiction was far ahead of its time. Lawrence Turman, a young Hollywood producer, thought it was better than the modest reviews it received and gave it to Mike Nichols to consider for a movie. In 1964 The New York Times reported that Nichols, by then a celebrated Broadway director, was scheduled to make his first film, The Graduate, in early 1965. But Nichols got distracted with the 1966 film version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which would become his directorial debut. It’s a good thing, too, because when The Graduate was released, in late 1967, it landed at just the right cultural moment to become the defining film of its generation.

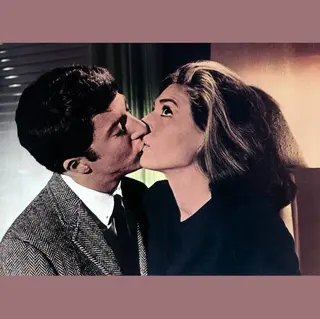

Dustin Hoffman as Benjamin Braddock and Anne Bancroft as Mrs. Robinson

The Graduate was the coming-of-age film for Baby Boomers, and it’s worth rewatching, not only as an insightful allegory about Boomer consciousness but equally for its incisive depiction of the perpetual divide from one generation to the next. The director’s visionary filmmaking, with his detailed camerawork telling as much of the story as the plotline, makes it all still feel implausibly contemporary to our 21st-century eyes. Nichols uses plenty of keen perceptual tricks. Continually, he opens a scene with a forensic close-up before the camera pulls back to provide a sweeping overview, or conversely, introduces a broad view before zooming in with laser focus on an intimate development. He also relies on transparency as metaphor, whether filling the frame with fish drifting in an aquarium or shooting through a wall of glass at lush, tropical backyard foliage. This intervening transparent surface is a visual device that underscores the once-removed experience felt by so many of the film’s characters.

Released in December 1967, The Graduate arrived at the tail end of the Summer of Love. At the time, the film’s portrayal of an older married woman having an affair with a young college graduate was avant-garde. But landing on the cusp of the sexual revolution, the antiwar movement and ongoing national race riots, the film’s sexual candor added a revolutionary currency all its own. While it was immediately celebrated for examining the confusion of the young graduate as a member of his alienated generation, no one at the time seemed to realize that the film gives almost equal status to the condition of a middle-aged woman imprisoned by the institution of marriage, beholden to her role as a mother and harnessed by the (upscale) social rituals of her circumstances.

Benjamin Braddock has just graduated from an elite East Coast college, and the film begins with his return home to Los Angeles. In the opening scene, the movie’s Simon & Garfunkel theme song, “The Sound of Silence,” hits a soothing harmony, even though the first line—“Hello darkness, my old friend”—portends a more melancholic story than the clean, bright, Californian visuals suggest. Initially Robert Redford was considered for the lead, but Nichols felt that his golden-boy good looks wouldn’t register the deep angst of Benjamin’s existential plight. It was the first star turn for Dustin Hoffman, then 29, playing the 21-year-old graduate. Doris Day turned down the role of sophisticated Mrs. Robinson because it “offended [her] sense of values.” Anne Bancroft, then 35, who had won an Oscar for her role in The Miracle Worker, plays Mrs. Robinson, a housewife in her mid-forties.

Hoffman’s Benjamin manifests the controlled panic of a trapped animal. On his first night at home, constrained by his proper manners, Benjamin tries to escape the graduation party his parents are throwing for him—the guests being all their adult friends. He smiles politely, shakes hands, and nods his way through a gauntlet of routine congratulations and anodyne small talk. At every turn Benjamin gets cornered by one well-coiffed suburban matron after another, the phoniness of his parents’ world animated by sharp, in-your-face close-up frames in which, for example, several older women converge on Benjamin at once—expressions exaggerated, hair lacquered, makeup meticulous. Garry Winogrand’s photographs of New York social gatherings of that period come to mind, where he captures the urban social mask as it borders on the comic and the grotesque. One guest—country-club tanned and dressed for the boardroom—pulls Benjamin aside and offers his investor’s vision for the young graduate’s future: “One word,” he says. “Plastics.” This became a cultural laugh line, putting its finger on the generation gap in that tumultuous decade.

“It’s telling that we never learn Mrs. Robinson’s first name, as if she is forever stuck in the identity of her marriage, frozen in the amber of her materialist California dream life.”

At first you wonder if Benjamin’s stunned-by-life detachment is the result of the academic rigors of his four years at college, but it becomes obvious that he is stultified by the brittle perfection of his parents upholstered suburban world and equally debilitated by more urgent questions about who he is and how he is going to spend the rest of his life. Benjamin is an older and more repressed version of Holden Caulfield, fed up with the hypocrisy of his parents and overwhelmed by the meaninglessness of everything. He spends the entire summer drifting in catatonic repose, half the time lying on a raft in the pool, the jewellike reflections of the sun sparkling on the glassy surface of the water, the leafy backyard a placid American-dream oasis for his inertia.

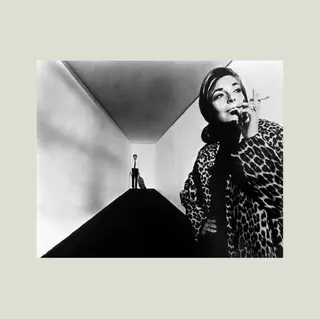

Enter Mrs. Robinson, the wife of his father’s law partner. The Robinsons are among his parents’ closest friends. Mrs. Robinson is bored, beautiful, elegant and haughty. She could have stepped out of the pages of Vogue with her beauty parlor–streaked hair, shoulder-length and falling winsomely over one eye, and her expensive leopard-print fur coat and au courant suede miniskirts. The photographer Richard Avedon, Nichols’s best friend, who shot the early publicity stills for the movie, no doubt had a hand in fashioning Mrs. Robinson’s icy-chic “Avedon woman” countenance. The night of the graduation party, she manipulates Benjamin into driving her home, then commences a subtle, if condescending, seduction, tormenting him with her MILF appeal, exploiting his obeisance, amusing herself with his confusion. She lures him upstairs to show him a painting, and then, in a canny move, leaves the room and returns naked. Dumbstruck and trying to navigate a conundrum of temptation against propriety, Benjamin is saved by the sound of her husband’s car in the driveway. He flees down the stairs and into the sunroom. When her husband comes in, he coaxes the young graduate into an affable nightcap. Benjamin sits there awkwardly holding his drink, assuming the burden of guilt, finding himself caught in the headlights of the Robinsons’ empty marriage.

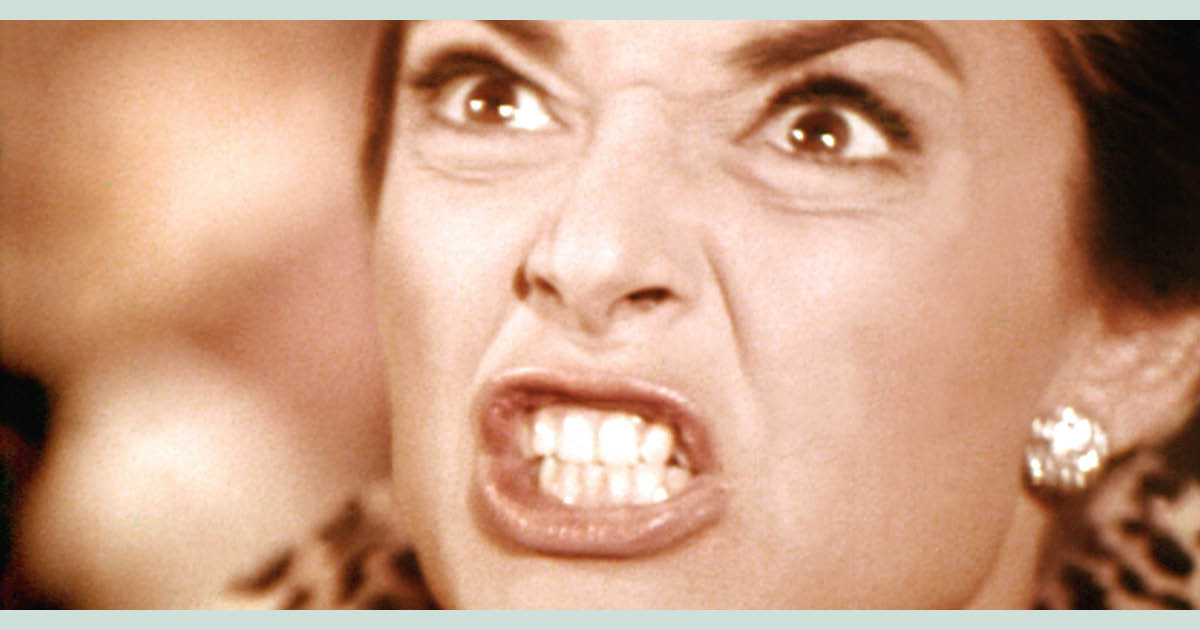

Mrs. Robinson drops her mask

Benjamin’s subsequent affair with Mrs. Robinson is the kind of initiation into sexual adulthood that adolescent boys dream about, although for Benjamin it lacks the za-za of that thrilling fantasy. But what is Mrs. Robinson getting out of it? Surely she turns him into her unlikely but convenient boy toy, with whom she wreaks her silent revenge on her husband and enacts her disdain for the seemingly enviable world in which she—as a woman of her generation—finds herself trapped. In one scene, lying in bed together during one of their hotel trysts, Benjamin complains that they never talk. “What do you want to talk about?” she says, irritated. Anything, he responds. Art, she suggests, seemingly pulling a subject out of a hat, one about which she will claim to know nothing. Yet later, fishing for information about her life, he learns that she met her husband, then a law student, when she was in college—studying art. Wistfully, she acknowledges that she wanted to be an artist but got pregnant and had to marry Mr. Robinson. She laments the fact that she had to sacrifice her ambition—a key to her predicament as a woman of her time. It’s telling that we never learn Mrs. Robinson’s first name, as if she is forever stuck in the identity of her marriage, frozen in the amber of her materialist California dream life.

While the film is undeniably Benjamin’s story, there is a strong feminist subplot afoot: Mrs. Robinson is suffering from what Betty Friedan identified in The Feminine Mystique, published the same year as Webb’s novel, as “the problem that has no name.” Friedan was referring to the unspoken supplication of all women to their husbands, not only legally but financially, culturally and emotionally. Mrs. Robinson not only endures that “problem”; she mercilessly takes it out on Benjamin. For her, the affair is a vent for her independence. Thirty years after crafting her most indelible role, Bancroft said of the character, “Mrs. Robinson was using sex as a way to diffuse this rage inside of herself.” It’s a far cry from Benjamin’s attitude toward the affair, going through the motions as a distraction from his own inertia; in one brilliant cinematic montage, he is filmed from above jumping onto a raft in the pool and then jumping on Mrs. Robinson in bed—in both cases returning to the symbolic womb, avoiding his own independence.

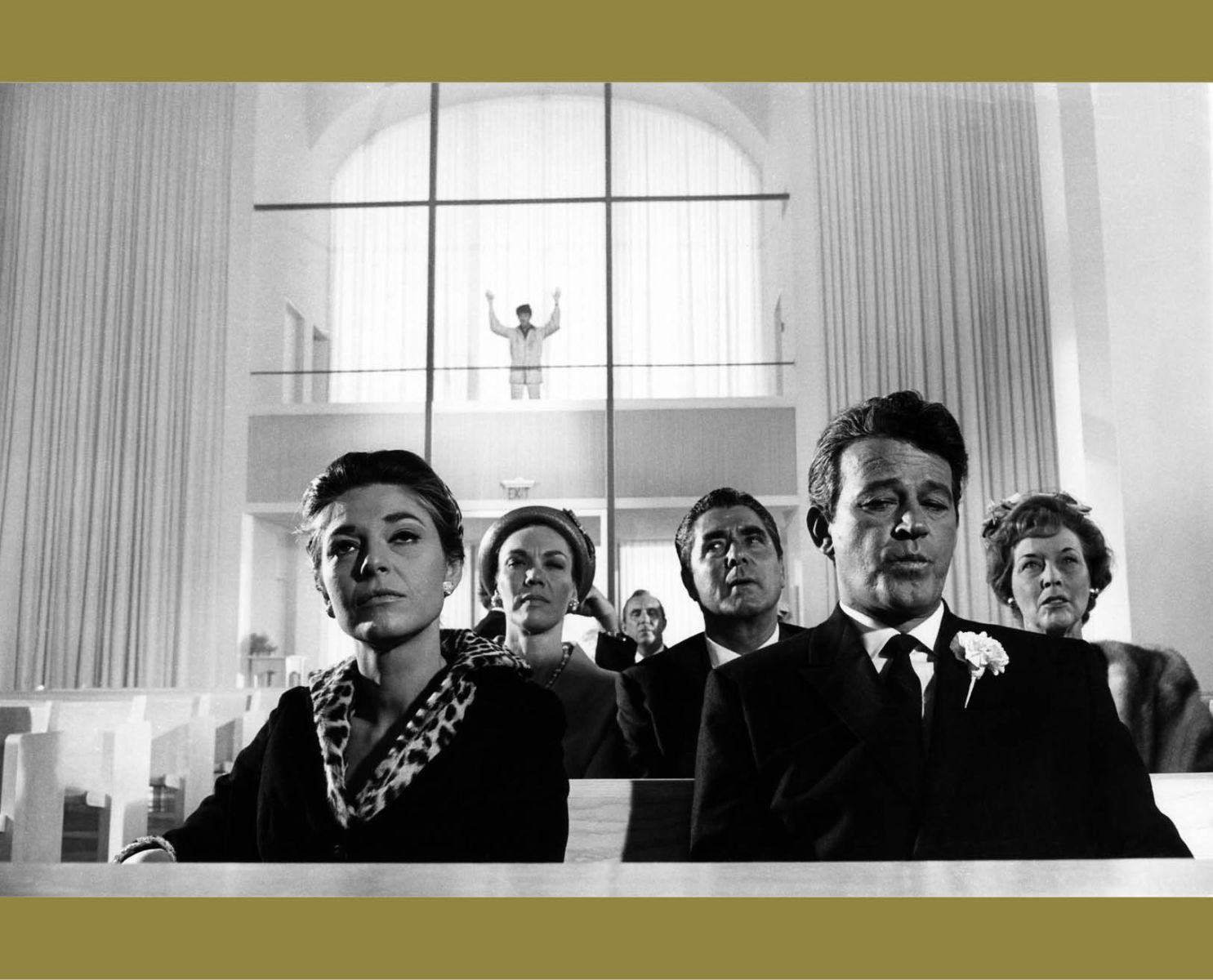

The generational divide, literalized

The incestuous crosscurrents of the affair not only confuse Benjamin, he is disgusted by the cynicism of it, its hollowness. To complicate matters, the Robinsons have a beautiful daughter, Elaine, a student at Berkeley who comes home for a visit. Mrs. Robinson draws a line in the sand, making Benjamin swear never to go near Elaine, yet Benjamin’s oblivious parents badger him into taking her out, if only, as they insist, to show respect to the Robinsons. Several wild plot twists will eventually bring Benjamin and Elaine together, but what has gotten lost in the analysis of The Graduate is Mrs. Robinson’s own universal rite of passage as a woman on the verge of menopause. For the movie is as much about her coming-of-age as it is about Benjamin’s. She is approaching her own “change of life,” as menopause was often referred to: She sacrificed her art to raise a daughter who is now grown. She forbids Benjamin, her lover, from seeing Elaine, as much to protect her daughter as to prevent her from taking Benjamin away, with her daughter now positioned as her rival.

In the film’s famous last scenes, Benjamin liberates Elaine from a wedding arranged by her parents precisely to keep him away from her. Elaine opts for Benjamin—the forbidden fruit—and the two flee the ceremony, she in her wedding dress, he not her husband. They jump on a city bus, sit in the back seat, look at each other and smile, having beaten the odds. Then they look straight into the camera, intermittently grinning and grimacing, registering a “what just happened?” kind of perplexity about the enormity of their unknown future, ending up a heroic couple—allies on their side of the generational divide. Meanwhile, our last glimpse of Mrs. Robinson—no sympathetic character, to be sure—was her failed attempt at stopping Elaine from running off. The movie leaves her stripped of everything: her husband, her lover, her daughter, her dignity and ultimately her own agency, a condition experienced by so many women of her generation. Today Mrs. Robinson seems not so much a villain as the victim of an era, falling into place among a legacy of female characters of the screen whose quiet indignation about the gaslighting norms in which they were societally demeaned caused them to behave badly. Here's to you, Mrs. Robinson....