Michael Mann’s Outlaw Sublime

By Christian Lorentzen

Michael Mann and Al Pacino on the set of Heat, 1995

Outlaw Sublime

Christian Lorentzen

The stylized poetics of Michael Mann’s burdened masculinity

November 17, 2022

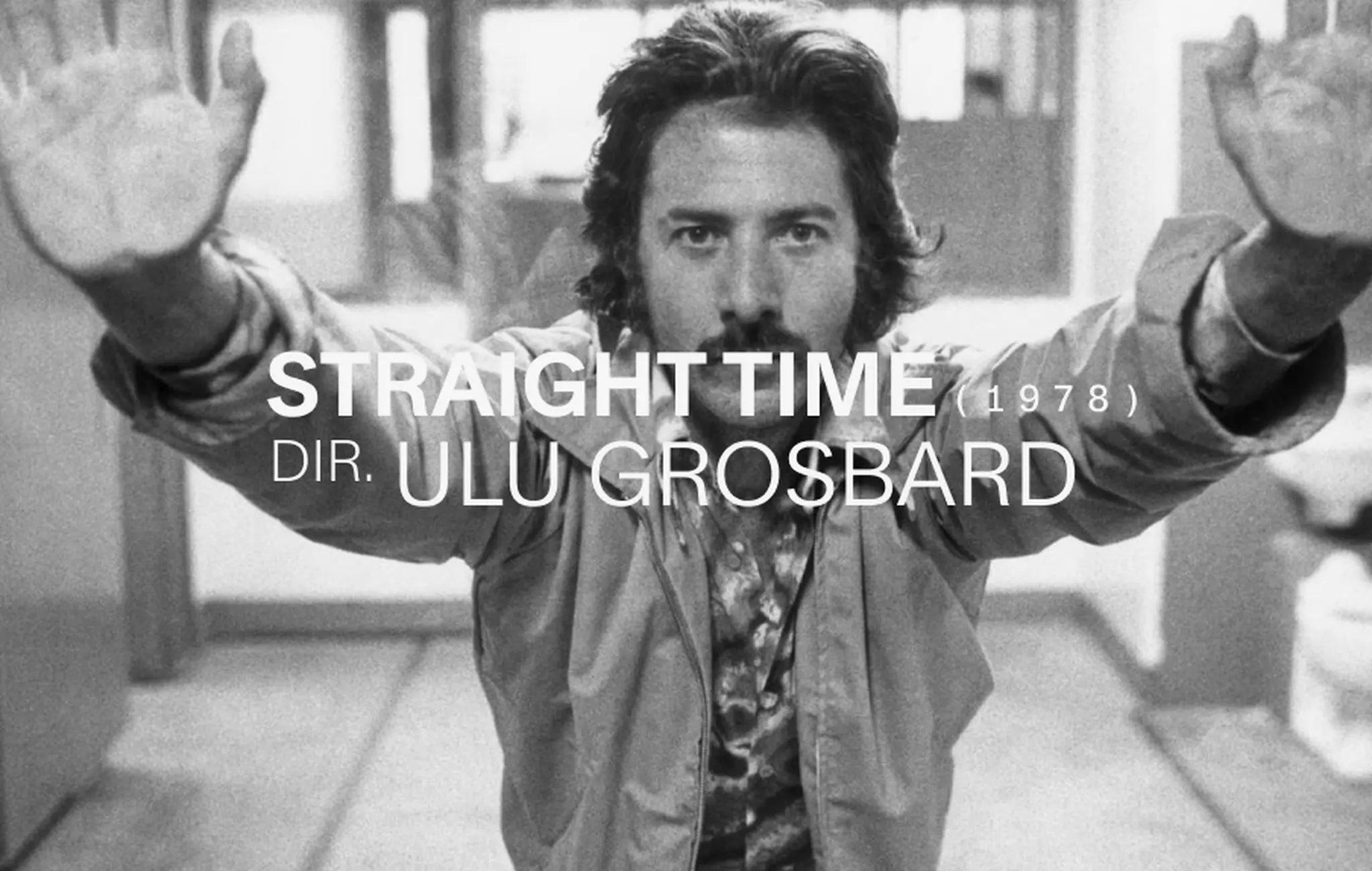

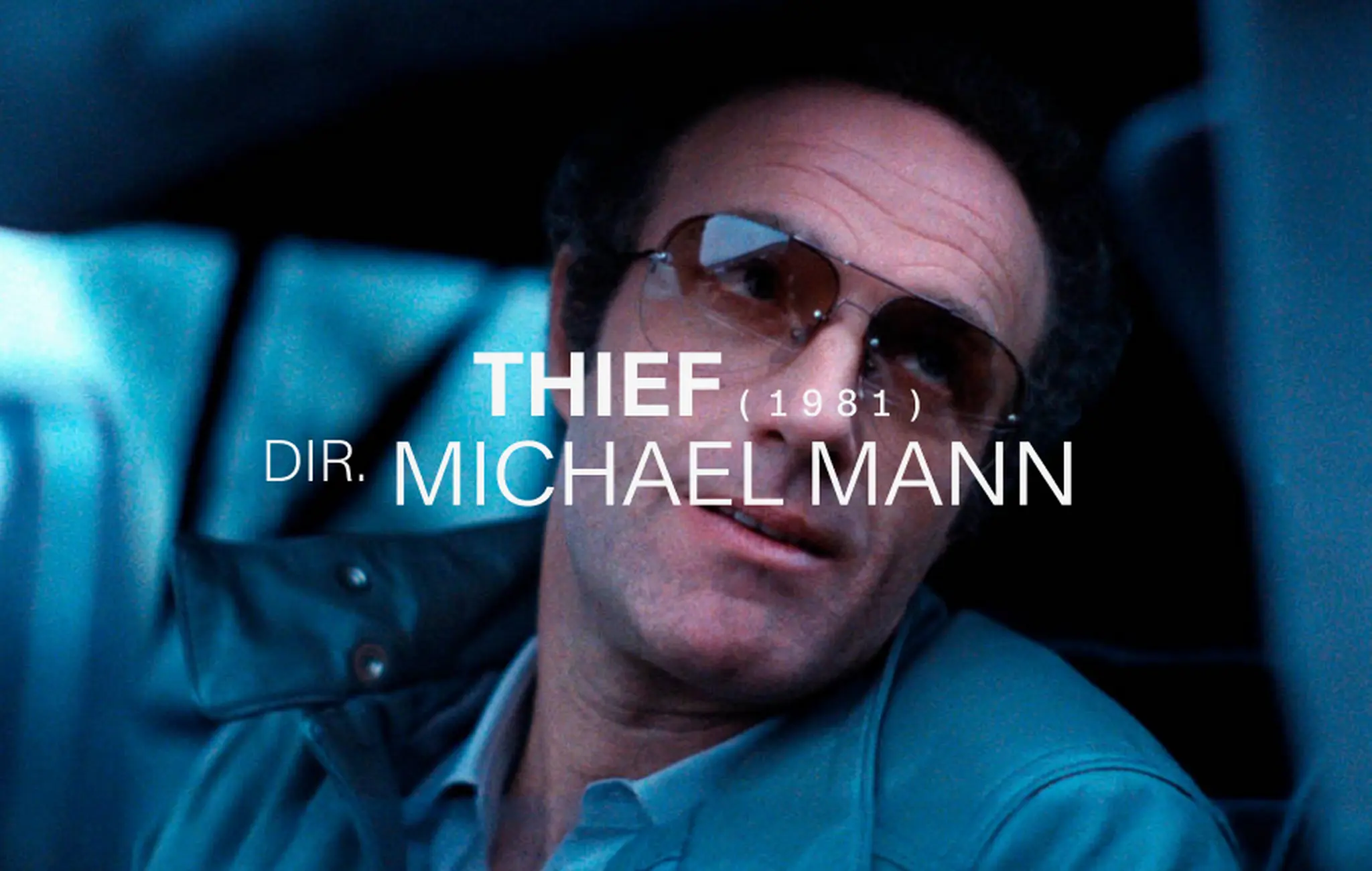

The scene is a diner overlooking a highway, and it is the array of white and green lights glowing circular in the distance and articulating a curve in the road that mark the scene immediately and quintessentially as the work of director Michael Mann. (That and the soft, ambient tones of the soundtrack by Tangerine Dream.) The film is Thief, from 1981.

Frank and Jessie, played by James Caan and Tuesday Weld, walk along a row of tables against the windows and sit down across from each other in a booth. They are in love, but the world is against them. She tells him the story of her relationship with a drug dealer, now deceased, who stranded her on a street corner in Bogotá. “He is dead,” she says. “That is good, because he’s an asshole,” he says. “There was love in the beginning,” she says. He tells her about prison, where he was from age 20 to 31, on a petty thievery charge that led to a manslaughter rap once he was inside. “You gotta get to where nothing means nothing,” he says. He tells her of fighting back against a beatdown—“hydrotherapy in the mental ward, a gangbang”—that he survived, maiming the guard who led it. Then he hands her a collage that he made in his cell and keeps in his wallet. “What is this?” she asks. “That is my life, and nothing, nobody can stop me from making that happen. And right there,” he says, pointing to the house in the top left corner, “that would be you.” She protests: “You don’t know from one day to the next whether you’re gonna be killed, go home, or get busted,” she says. She is infertile. He says they can adopt. “I was just thinking, you know, that just maybe between the two of us that we could make something happen, something special, something really nice.”

Of course they are doomed. Of course the beautiful, stylized naturalism of the way that they speak to each other means they’re too good for this world, no matter how bad they’ve been. Of course the thief’s last big score, the one that will set him free, will ultimately bring him down. It’s the same in Heat, Mann’s central work of 1995, which he’s now followed with a sequel in the form of a novel. The last big score never comes off, no matter how disciplined you are, no matter how true your romantic intentions. It’s the discipline and the romanticism that make the Mann hero. This holds in the main line of his work—the contemporary thrillers Thief, Manhunter, Heat, Collateral, Miami Vice, and Blackhat—as well as in his deviations into historical costume drama (The Keep, The Last of the Mohicans, Public Enemies) and topical biopics (The Insider, Ali). Mann’s cinema is cold and stoic but shot through with a fairy-tale heart. How many movies about expert bank robbers have ever made you cry?

![]()

Thief, 1981

![]()

Heat, 1995

Call it the outlaw sublime—a style that channels the tradition of the American tough guy and re-aestheticizes the hardboiled existentialism of the 1930s and ’40s for the postmodern era. Mann’s romanticism may be retro, but he and his characters move through an ultramodern world of networked security systems, ubiquitous surveillance and globalized capital. There’s a continuity to his historical epics and sleek crime pictures. Whether set among the tangled freeways and glass towers of Chicago, L.A., or Miami; the pre-Revolutionary wilderness; or the hardscrabble streets of Depression-era America, Mann channels the same visual grandeur and parses the same logic of honor. He belongs to the generation that arose in the aftermath of studio Hollywood and the flourishing of the French New Wave. Like his contemporary Jean-Jacques Beineix, he took the themes of the golden age of noir and expressed them in a painterly visual style, with debts to Jean-Pierre Melville and Stanley Kubrick. (Mann cites seeing Dr. Strangelove as a teenager as the event that made him become a filmmaker.) The risk of the romantic and the dealer in types is slickness that can veer toward the pornographic, but Mann has always compensated with a deep commitment to the authentic. He collaborated with actual cops and robbers, beginning with his uncredited work on the screenplay for Straight Time, the 1978 adaptation of Edward Bunker’s novel No Beast So Fierce. At the age of 17, in 1951, Bunker became the youngest ever inmate of San Quentin State Prison, where he was a bookworm (see also: Chris Hemsworth’s jailbird hacker in Blackhat). He was in and out of prison until the mid-1970s, when his writing career took off. Bunker is the inspiration for Jon Voight’s criminal fixer Nate in Heat and served as Mann’s advisor on the film. Another frequent co-conspirator, Dennis Farina, was a Chicago cop for eighteen years before Mann brought him in as a consultant on Thief and then cast him in a small role, kicking off his decades-long acting career. Authenticity is overvalued in today’s culture, but one thing it allows an artist to do is deliver the goods with a straight face.

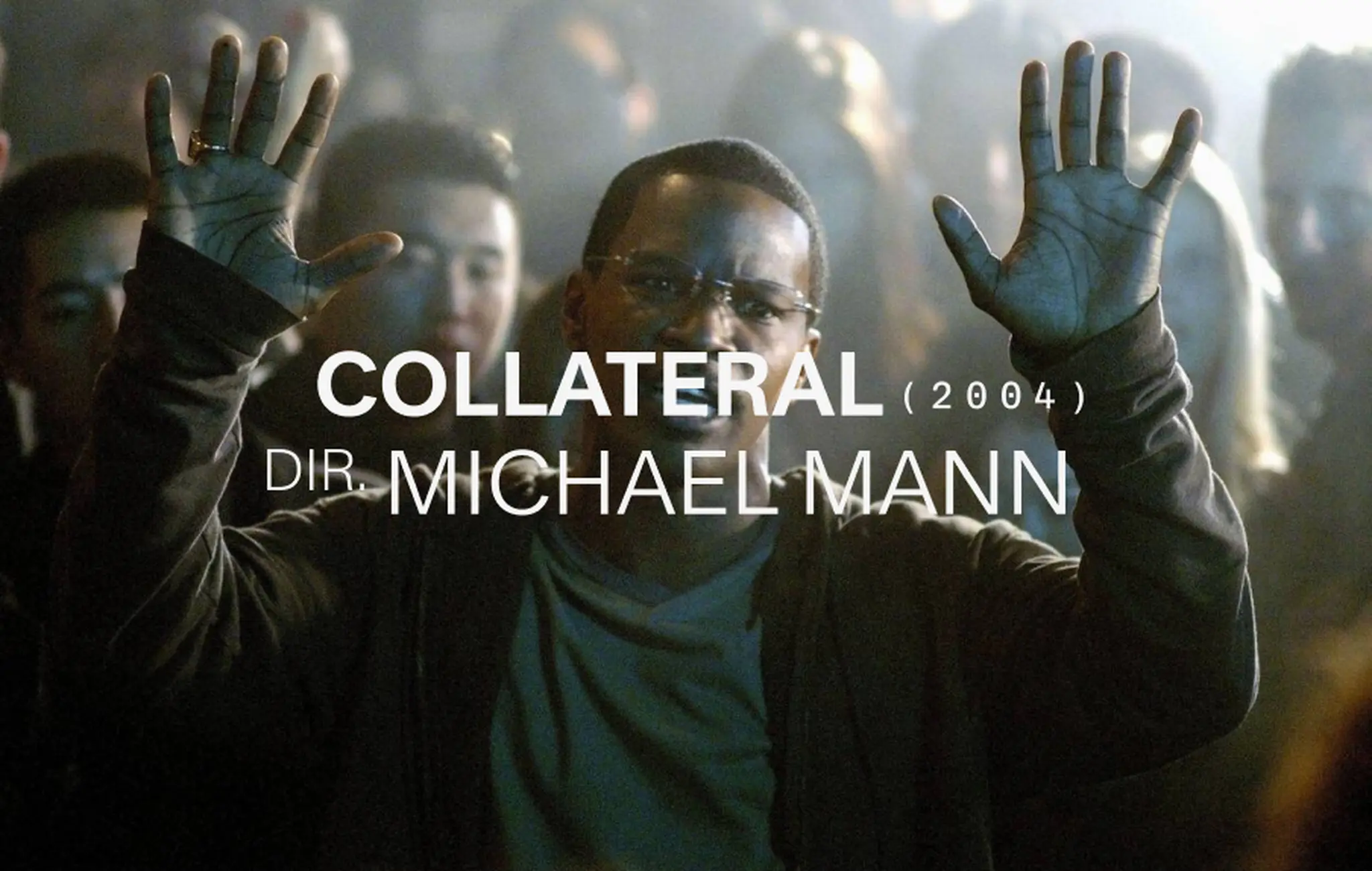

The poster for Heat, Mann’s 1995 L.A. heist epic, shows the faces of Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, and Val Kilmer, the last of whom, at the height of his career, agreed to take a supporting role if his face was on the poster between his elders. They are, notionally, the film’s main characters: the Master Detective, Pacino’s Lt. Vincent Hanna; the Master Thief, De Niro’s Neil McCauley; and the Apprentice Thief, Kilmer’s Chris Shiherlis. On the outskirts of LAX, with jets screaming across the night sky, the Master Detective will, in a face-off between a generation’s two most celebrated actors, kill the Master Thief, and the Apprentice will escape, barely, to live another day. These characters—and variations on the Master/Apprentice and Cop/Outlaw archetypes—embody the tragic idea of manhood Mann has traced across the eleven films he’s directed, not to mention several television shows and other films he has written or produced. Mann’s men are obsessive but tortured, brutal but romantic, bound by personal codes but fated often to bring about their own undoings. They are consummate professionals in risky businesses: crime and law enforcement but also journalism, chemistry, boxing, hacking, and so on. Mann could turn a cab driver into an epic action hero. In Collateral, he did.

But there is another kind of Mann character, and in Heat he is the one who drives the plot. His name is Waingro. He is a human MacGuffin. He is no anti-hero, but rather Pure Rogue Villain, slippery and without honor. (This type recurs across Mann’s work as well: in Gabriel Byrne’s Nazi officer in The Keep; the FBI agent who tortures suspects in Public Enemies; the tobacco executives in The Insider.) As Waingro, Kevin Gage, with a beard and stringy long hair draping from a balding pate, looks like Jason Momoa but white and out of shape; it’s a stark contrast to Pacino’s flash style (Hanna as middle-aged man ready to strut through the club to hit up an informant) and De Niro’s slick impression of a corporate salesman (“I work in metals,” McCauley says to the bookstore clerk he picks up). Waingro is the weak link replacement member of McCauley’s crew, the psycho who kills the armored truck guard unnecessarily, drawing a potential murder rap onto what was meant to be just a spectacular heist. Hanna later uses Waingro as bait, putting it on the street that he’s holed up in an airport hotel, knowing McCauley will want vengeance if he can get it on his way out of town. Two of McCauley’s creeds collide: the jail yard code of honor that demands he take revenge and the thief’s imperative, “Have no attachments, allow nothing to be in your life that you cannot walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you spot the heat around the corner.” He goes down not because he got attached to a woman, a child or a friend, but to revenge itself.

As McCauley and Hanna are foils to each other, Waingro is a foil to each of them. He represents the sort of crook McCauley is not: sloppy, a sadist given to impulsive violence (“I had to get it on,” he says of the guard he killed), a killer of innocent women and easy to track down. (In Mann’s universe, the sadist is always the enemy, whereas for his contemporary David Fincher sadism is the object of endless fascination.) He is born to lose in a way that McCauley and Hanna are not. McCauley is not a predator of the innocent. His crimes are not meant to have individual victims. He takes his scores from corporate entities and big banks and tries to get away without drawing blood. Even the banks and the assholes won’t take the hit: Insurance companies will. Waingro is not the sort of perp Hanna is meant to go after; he’s unworthy. Hanna is Major Crimes Unit. He chases the highline crews, like McCauley’s. Next to Waingro’s depravity, incompetence, reliance on luck, and lack of discrimination (“I am a cowboy,” he says as he sits down at a dive, “lookin’ for anything heavy”), McCauley’s self-control, precision, and adherence to an honor code render him noble. Hanna becomes not just a cop on the beat—the sort people lately want to abolish—but an artist of detection.

“How many movies about

expert bank robbers have

ever made you cry?”

It is a strange experience reading a novel when you know all the characters already as famous actors from an iconic movie. When Heat 2 debuted at No. 1 on The New York Times bestseller list the week after its release in August, Mann tweeted: “Gratitude to the actors that brought these characters to life.” It is impossible to read about McCauley, Hanna, and Shiherlis without thinking about De Niro, Pacino, and Kilmer. It is a sensation I remember from reading novelizations of movies as a boy in the early 1980s. (I don’t think of Keira Knightley when I reread Pride & Prejudice.) The questions I had while awaiting the arrival of Heat 2, which Mann wrote with the crime writer Meg Gardiner, were simple. The book was billed as both a prequel and a sequel. How could a prequel narrative bring together Hanna and McCauley if they had never encountered each other before? How in the sequel would Mann deal with the deaths of so many characters within the action of Heat? Not just McCauley, but also Trejo and Cerrito from his crew, not to mention Waingro himself. Beyond questions of plot, how would a Michael Mann movie play on the page? Would the novel be any good as a novel?

As a novel Heat 2 isn’t bad, though a middle section set Ciudad del Este—a free-trade zone on the borderline where Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil meet—drags a little, despite the city’s lawlessness and intrigue. The novel’s best parts call to mind the French thriller writer Jean-Patrick Manchette’s elaborate scenes of spectacular violence. The climactic freeway pile-up and shootout are drawn to match the military-style gunfight that ensues after the bank heist in Heat. A raid on a drug cartel’s cash stash house, a disused motel just over the border in Mexicali, is sketched in forensic detail. There are home invasions and a fatal desert confrontation. There are sex scenes (not as spectacular as the violence) and backstories (Hanna and McCauley both served in Vietnam—not exactly a surprise). There are good lines and only a few bad ones. The dialogue is mostly excellent—nothing quite matching the gutter eloquence of the Thief diner scene, but plenty to relish. A few phrases from the film are trotted out for another go: Hanna again tells someone not to “waste his motherfucking time.” He does not scream about the quality of anybody’s ass.

The prequel and sequel are interwoven, so McCauley is in the mix for most of the book. In 1988, a bank heist in Chicago yields computer disks that clue McCauley into a cartel’s freight practices, the southbound freight being cash. Hanna, meanwhile, is after a crew that does home invasions and forces residents to open their safes before tying the job up with murder and rape. The leader of that crew, Otis Wardell (consider the Pacino enunciation), has a link to McCauley: They get their vehicles from the same connection. Wardell, another sadist, is the novel’s Waingro. He makes McCauley into a tragic figure by murdering his girlfriend and stealing his score, despite McCauley’s heroic efforts to save the woman. Years later in L.A. Wardell turns up and offers both Shiherlis and Hanna opportunities for redemptive heroism. (Hanna is in no need of redemption, actually, except with respect to his ex-wife Justine.) In Heat 2, we learn more about Hanna and McCauley’s early lives, but neither of them behave in ways that would surprise a viewer of Heat: The precision, the obsession, and the sense of honor are all intact. In the 1980s Hanna does cocaine and in 2000 he pops Adderall pills prescribed to his stepdaughter. Shiherlis is allowed to develop, as they say. In the prequel we learn how he met his wife, Charlene, played by Ashley Judd in the film, a call girl in Las Vegas. In the sequel, he goes into exile, working for a Taiwanese crime family operating out of Ciudad del Este. He sheds his bad habits—drugs and gambling—and falls in love with the boss’s ambitious daughter. He grows up. It’s tempting to say that he becomes more like McCauley, but it’s hard to imagine McCauley working for anybody, much less the woman he goes to bed with.

![]()

Russell Crowe in The Insider, 1999

![]()

Al Pacino in Heat, 1995

Over time the women in Mann’s work have gotten in on the game of cops and robbers. This is not true in Heat, in which all the women are civilians who are more or less kept out of their men’s work of crime and detection. In Heat 2, Shiherlis’s girlfriend, Ana, follows the heroines of Collateral, Miami Vice and Blackhat, all of whom are partners or adversaries in the game. These steely women aren’t quite femmes fatales; they don’t bring about the men’s demise. There are still damsels in distress around, victims and innocent bystanders: In the prequel Hanna spends hours by the hospital bedside of a teenage girl in a coma after one of Wardell’s home invasions, telling her stories of his life as a cop. (I don’t see more than a minute or two of these passages, which recall Hanna’s stepdaughter in hospital after a suicide attempt in Heat, making it into the film version.) This evolution has only brought Mann’s romanticism closer to the center of his works, putting love and desire on the same plane as crime and detection, sometimes literally. Heat 2’s mythic climax is another episode in his life’s project of making a potent combination of action and existentialism.

“…PUTTING LOVE AND DESIRE ON THE SAME PLANE

AS CRIME AND DETECTION, SOMETIMES LITERALLY.”

The pulp and the romance, the good-guys and good-bad-guys and bad-bad-guys plots rescued from triteness by the utter seriousness of their stylization in sound and image—does this work on the page anything like the way it works on the screen? The answer is no. “Neil drives the highway alone as the night turns into morning twilight”—many of the scenes in Heat 2 begin like this, with mention of the sky and the quality of light. You read them knowing their plainness will be exceeded when this entertaining but slight book is transformed on film. Heat is a movie Mann made twice: first as a television film that was to serve as the pilot for a series that never got picked up, next with famous actors and a budget of $60 million. Those versions and now this book are the product of his own longtime obsession with Chicago detective Chuck Adamson’s pursuit of the real-life criminal Neil McCauley. (A similar palimpsest quality has marked his approach to Miami Vice: first television, then motion picture, finally transposed back to television and to Japan for the recent Mann-produced HBO series Tokyo Vice.) Now pursued to the last years of his career—Mann is 80 years old—that obsession marks him as a man out of his own films. Whether or not Mann, whose painstaking methods typically translate into years of production for each film, will have the chance to bring Heat 2 to the screen, he has put down the blueprint for his last big score. If, like McCauley, he goes down too soon, surely an Apprentice will pick up the job.