Love is Strange

By Lawrence Osborne

Oasis, dir. Lee Chang-dong, 2002

LOVE IS STRANGE

Is Lee Chang-dong’s wildly twisted, shockingly unorthodox Oasis the greatest love story in 21st-century cinema?

By Lawrence Osborne

December 8, 2023

Oasis, South Korean director Lee Chang-dong’s third feature, from 2002, opens with a cheap, mass-produced tapestry hung upon the wall of a dark and equally cheap apartment. In it we see a baby elephant, an Indian woman and a small boy standing inside a garden. Under them the single word oasis is stitched in black against a gold background. Shadows of branches moving against a nearby window play over the tapestry’s surface, filtering nocturnal street light. It’s a windy night. We have no idea what the tapestry’s image means, if anything. And yet we sense that the occupant of this room must spend a lot of time looking at it, because there is so little else in the way of decor. Who is this trapped occupant?

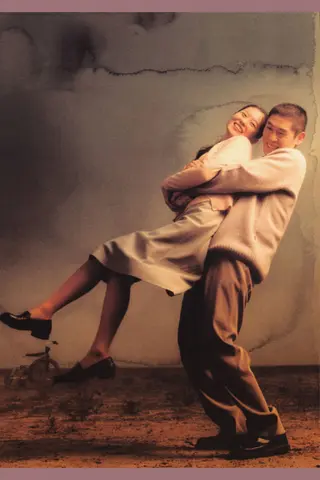

Stills from Oasis, starring Moon So-ri and Sol Kyung-gu

We first meet her through her gaze, presumably the following day, as she directs her eyes at what seem to be paper butterflies floating through the air. These butterflies turn out to be beams of light, and we soon discover the person who is shooting them around the room: a young woman with severe cerebral palsy. Her limbs are so twisted that she cannot unravel them enough to perform even the simplest motor tasks, yet she is able to use a mirror to create dancing reflections; her eyes are locked into a permanent cross-eyed grimace. Han Gong-ju (played by the brilliant then-27-year-old actress Moon So-ri) lives isolated and housebound, visited occasionally by her exasperated family, and from the simple elements of her room she is able to create little worlds to keep her mind alive. Her family are lower-middle-class city dwellers caught up in their small and humdrum hypocrisies, plots and gossips, and their disabled sibling is usually little more than a burdensome afterthought. Into this claustrophobic and hopeless miniature world, which Gong-ju cannot exit by herself, comes a recently released petty criminal named Hong Jong-du (played by the equally brilliant Sol Kyung-gu). Jong-du calls on the family to seek reconciliation for committing an accidental vehicular hit and run, which has killed Gong-ju’s father.

Jong-du soon discovers that the son, Han Sang-shik, and thus Gong-ju’s brother, is using Gong-ju’s disability money to fund a nicer apartment while letting the neighbors look after his half-abandoned sibling. Her family is disgusted by the sudden appearance of Jong-du, whom they presumably know only from the trial. But Jong-du becomes enchanted by the disabled sister. He discovers that the keys to the girl’s apartment are hidden in a pot on the outdoor landing. And so we sense, very early on, that Oasis will be a twisted and fabular obsession story whose initiation is subtly menacing. What is less predictable is that it turns into a modern love story.

“It’s hard to imagine any other director navigating this explosive territory with such cold-eyed intensity.”

Lee has said in interviews that relying on any cinematic tropes or romanticizing effects while shooting Oasis was anathema. “Cinema, like love, is a fantasy. My intention was to avoid an artificial fantasy.” This entailed getting rid of “movie-like angles, camera movement and lighting.” He wanted to shoot Oasis, which is set in modern-day Seoul, “unfashionably.” This rule also applied to the subject of love itself. Lee’s love story would wrangle directly with all of the elements that contemporary culture has lost or purposely neglected when covering the romantic ideal. The director’s approach strips away the usual dramas and instead portrays a sexual relationship between two psychologically mutilated and abnormal people deprived of all ability to act out those dramas.

Jong-du is a complex character, particularly in the role of romantic lead: He’s a twentysomething with a stooped frame, a compulsive nose-wiping tic and a habit of cocking his head and grinning awkwardly. Lee has explained that he wanted to create a character who was both filled with common sense and utterly incapable of it, both cunning and sane and, on the other hand, mentally disabled in some vaguely autistic way. “He looks ruined and also innocent. He’s in between,” Lee says. Accordingly, as the film progresses the character proves perpetually remorseful and perpetually—simmeringly—violent. “Jong-do isn’t a fool, but he’s not intelligent either.” A semi-madman straining for sanity.

In one scene early in the film, Jong-du eats at a restaurant knowing he can’t pay the bill, offers his tatty shoes as a guarantee to the owner, and flees barefoot into the winter streets. Taken in at first by his younger brother, Jong-du’s erratic behavior soon has him relegated to working as a delivery boy for a Chinese restaurant. Then, when he gets fired from that, he is taken on at his older brother’s auto-mechanic shop. But nothing works for Jong-du. He is an incorrigible misfit given to bouts of antisocial mania and uncontrollable disruption. He rolls through the film as a dangerous and unpredictable force whose motives can never be divined. But what happens when he decides to sneak back to Gong-ju’s building and purloin the hidden keys in order to let himself, uninvited, into her apartment?

What follows is surely one of the most disturbing and tensely dark scenes in contemporary cinema. The girl is obviously shocked to see this stranger and yet at the same time it is the first intrusion into her world of someone unexpected. We see a flicker of ambiguity come over her. But because he is unable to react normally, Jong-du clumsily engages in a sexual assault, or rather he tries to. Then as her outrage and horror overwhelm him, he beats a groveling and humiliated retreat, but not without leaving her his phone number. He replaces the key in the pot and escapes, fearing that he will be jailed a second time if discovered. Jong-du returns to the auto-mechanic shop where he has been holing up and awaits the appearance of the police. What happens next, however, runs counter to all expectations. Late at night Gong-ju hauls herself to her phone and manages to punch in his number. The failed assault has failed to wreck the budding sympathy each holds for the other. She calls to chat, flirt, initiate a friendship—and eventually to suggest he come back to visit her.

It’s hard to imagine any other director navigating this explosive territory with such cold-eyed intensity. But Lee has shown the same virtuosity in all his films. These range from a story-told-backward in his second film, 1999’s Peppermint Candy, which explores the suppression of the student-led Kwangju Uprising in 1980, and 2007’s Secret Sunshine (in which the sublime Jeon Do-yeon portrays a woman grieving her abducted son) to his 2018 film Burning, a mystery drama based on stories by Haruki Murakami and William Faulkner that takes us into a love triangle driven by a pyromaniac obsessed with burning down greenhouses. In Lee’s films things seem not to happen in a linear way, but we always understand why emotional explosions occur—and without caring whether highly charged scenes have been explained by means of a normal narrative. The unpredictable irrationality of human nature is perfectly captured.

From left: Burning, dir. Lee Chang-dong, 2018; Secret Sunshine, dir. Lee Chang-dong, 2007

Lee, like all great directors, has his own spiritual landscapes, and the audience is pulled into them by his unobtrusive style that favors a quiet, unassuming poetry and an equally quiet frankness. There is a scene in Oasis where the two ill-fated lovers descend into the Seoul subway, Jong-du carrying Gong-ju on his back, and for a moment she snaps into physical normalcy that enables her, fantastically, to dance with Jong-du. In fact, this fantastic transformation happens several times in the film, and most beautifully with the very figures depicted in the tapestry in her apartment. The elephant, Indian woman and boy come alive and dance with her in her room and we see, as it were, the healthy woman inside the afflicted one. A similar unorthodox scene occurs in Burning, when the main protagonist suddenly dances to a fading sunset while taking off her clothes, as the two men in love with her look on in astonishment. Thanks to Lee’s elegant, matter-of-fact approach, the scene doesn’t feel voyeuristic, but rather signals the magic and spontaneity of a life that fails expectation and shifts in any direction the characters want to take it.

It is the depiction of these mysterious shifts, which are never foreseen by the viewer, that makes Lee such a masterful experimentalist—fighting all tropes of narrative plotting that have been etched in stone by decades of Hollywood script doctors. Instead, moments are allowed to simply happen. Can a girl with severe cerebral palsy fall in love with an autistic criminal who tried to assault her? It takes a lot of guts to turn such an unappealing premise into the moving and profound masterpiece that Oasis ends up being. Ironically, it’s arguably the greatest love story to date in 21st-century cinema. The film was honored at the Venice Film Festival, where Lee won the Silver Lion Best Director prize, and yet it has always been something of a sleeper within Lee’s collective work. Oasis also typifies the harrowing intensity that the director puts his actors through to achieve such extraordinary complexity. In a documentary about the making of Oasis released shortly after the film, we not only grasp the commitment which Moon So-ri brought to her role, but the intense pressure it took to extract such a performance. The actress explains that she had to train her body to move, breathe, speak and gesticulate in wholly new and tortured ways, learning as she went along to force human emotion into a totally unfamiliar kind of expression. The torment paid off. It’s a tour de force performance even if, as she admits in the documentary, it left her teetering on the edge of an emotional breakdown.

At the end of Oasis, after the couple’s lovemaking has been discovered by the horrified family and Jong-du has been arrested for assault (now the wrong assault, of course), we see Gong-ju alone in her apartment just as she was at the beginning, but now she’s diligently dusting the floors to keep the place tidy for Jong-du’s eventual release from prison. It might be years, but she will dust every day until her ill-fated lover returns.

Peppermint Candy, dir. Lee Chang-dong, 1999; Yoo Ah-in in Burning