Johnny Jewel's Auras

By Robert Bound

Johnny Jewel onstage with the Chromatics in Oslo, 2019

Johnny Jewel’s Auras

In his artful forays into film composing, the cult pop icon distills violence, fantasy and color into ambient noise

By Robert Bound

February 20, 2024

The California-based musician, record producer and film composer Johnny Jewel is best known as a member of the electronica bands Chromatics and Glass Candy, as well as for being a co-founder of the Italians Do It Better record label. But you’ve definitely heard his sometimes beat-driven, always ethereal synths across cinema and television. Jewel worked with Ryan Gosling on his directorial debut, Lost River (2014), and with Nicolas Winding Refn on Drive (2011) and Bronson (2008) before appearing in David Lynch’s 2017 Twin Peaks reboot. Jewel has twice collaborated with Belgian director Fien Troch—described by Galerie curator Lukas Dhont as Belgium’s “national treasure”—first on Home (2016), about teenage delinquency and second chances, and more recently on Holly (2023), a psychologically intense study of a small community shocked by a tumultuous fire but soothed by a teenage girl’s healing powers. Jewel spoke to Galerie from his home in the desert near Joshua Tree.

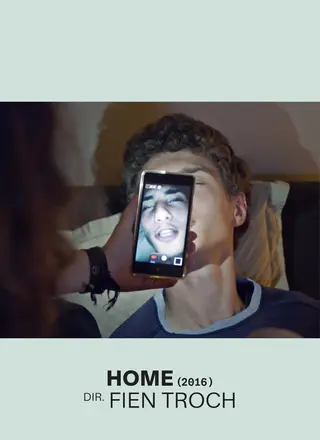

From left: Home, dir. Fien Troch, 2016; Holly, dir. Fien Troch, 2023

Johnny, how did you meet Fien Troch and what were the beginnings of your working relationship?

It began when I was in L.A. working on Lost River (2014) with Ryan Gosling, who was working with this Belgian editor, Nico Leunen, who had come over from Brussels and happens to be married to Fien. Toward the end of working on Lost River, Nico told me that when Fien was making Kid (2012), she was experimenting with a lot of my music. Then he told me about Home (2016). Nico said, “I have a sizzle reel, which is five minutes long, and then I have a four-hour version, all in Dutch with no subtitles. Which one do you want to see?” Obviously I said I wanted to see the four-hour version! I had a few questions because I don’t speak Dutch, but I was responding emotionally and fell in love with the project. I met Fien just after that.

What set the tone for the Home soundtrack?

Well, part of the concept for Home was that it would have some of the feel of a documentary—it wasn’t supposed to feel fictional. This informed the camerawork, the panning. Fien’s team were really fired up by the Frederick Wiseman documentary High School (1968). Fien wanted to have some type of score, but she didn’t want to have character themes or anything similar, because it would take us out of the realism. A score is essentially fantasy—no one walks around with a symphony playing to their every move. In real life there’s a lot of silence. So a lot of the music I did for that film took one of two directions: I’d come in through the back door and creep in, sort of blurring the line between sound design and score with ambient music, or we would just slam in with needle drops of some of my pop songs.

A playlist of Johnny Jewel's music in film

Your work for Holly seems different again. What information or impetus do you need to kick off a project?

Some time later Fien let me know that she had written a new film with the working title Fire. She told me that it would be quite different from Home and asked if I’d be interested. She sent a script for what became Holly, then a rough assembly of the film with a lot of my temp work that Nico had put in—a bunch of things from Home, things that didn’t get used. I just went straight to the piano and wrote the main motif because I could tell instantly that the film was much more narrative and more traditional in that way where I could introduce character motifs. Generally there are a few questions that I like to ask a director right off the bat. First, does your film need music? Basic but essential, right? Then, if you had to choose a color, what color would the film be? And this is before I know anything about the story or the characters or anything.

And what answers did Fien give?

I never asked Fien that for Home, as the music for the project started as a patchwork of temp music of mine that Nico Leunen had from the sonic library of Lost River. They had worked on the initial assembly for Home before asking me to join the project. Fien is very humble, and she didn’t make any assumptions that I would connect with her film. For Holly we discussed the color green early on. I often thought of the shot of the trees swaying in the breeze and the field of grass Holly is sitting on when her healing gifts first begin to show themselves.

“I like to boil it down. To say as much as you can with as little as possible.”

Generally, how good are filmmakers at answering those direct kinds of questions?

They’re usually caught off guard. That’s not my intention, but it’s really useful to know what the director is trying to convey psychologically through music. I want to get them into a conversation where they can speak to me almost subconsciously rather than try to meet me halfway [by] speaking a musical language. Because I don’t need to know musical terms from them. I don’t necessarily want to hear musical references from other films. I prefer to enter the world psychologically with the director, because ultimately my job is to help convey what’s not on the screen to the viewer, to bridge the gap between what the director is able to capture—what they’re able to say with words and with photography, location and editing—and then the part that they’re unable to say, that they can’t quite reach into. Basically: What is the goal? What do you want people to feel? How do you want this to read?

Are you aware of approaching film composition in a different way to other composers?

Well, I’m not sure about that, but I know that a lot of composers won’t touch anything until picture lock. But for me, I like to work even before shooting has started, if possible. That’s what I did with Ryan on Lost River. Because I don’t compose for films year-round—I write pop songs and albums and produce music, so I’m picky about what film work I take on. For me the primary reason for taking something on is a creative decision. And so I like to be as involved as possible and grow with it and discover it alongside the editor and the director as it’s morphing. I like to boil it down. To say as much as you can with as little as possible.

How do you choose your collaborators, both for films and making records?

It’s really about the connection. Is there a spark there? Could we do a dance? Because if we can, then it doesn’t really matter what the genre is, what the record is or what the film is. If I’m working with bands, I would never get in a studio situation where I’m a hired gun and there was no chemistry. And then, from a practical stance, it’s timing. Sometimes something like Twin Peaks [Jewel appeared with his band Chromatics in the 2017 revival series] will come along and I say, “Okay, I’ll stop everything because I really want to work on this.” There are times when I do not want to hear any requests, and there are other times when I have a bit of a breather. I’d done a lot of beat-driven music during the pandemic. I made a bunch of pop during that time, and then I wanted to get back to doing something a little bit more abstract once I started touring again. Holly came along at the perfect time. I hadn’t done anything for several months that was even remotely in that world, so it was a real creative outpouring.

From left: Matt Smith in Lost River, dir. Ryan Gosling, 2014; Luka Mortier, Loïc Bellemans and Lena Suijkerbuijk in Home

How do you start creating a palette for a character or the tone of voice for a film?

I wonder first and foremost, a little like the question of color, about the tone. Is this a metallic tone? Is this a wood-based tone? Is this something synthesized? Is this something percussive? I’ll present the idea of that tone to the director and ask: “What do you think of this type of voicing? Beyond musical melody or anything, here is a sound that’s a character identity. This is what I’m feeling.” And filmmakers are almost always willing to hear it. Then I try to realize that within the melody or within the chord structure. For Holly, she’s a 15-year-old girl and there’s an innocence there, especially at the beginning of the film. I really wanted to have something reminiscent of childhood, so I wanted something like a music box. And then there’s the weather in this film, the wind outside, all the wind in her hair, how messy it is. There is this invisible force that’s moving a visible thing that, to me, played into the idea of the paranormal or supernatural aspects to Holly’s gifts. And for that I really wanted to push tones that were airy, that sound windy—say, synthesizers as flutes.

There are certain habits—classical music for films set in space, for example—that seem to have stuck in soundtracks. Are there any rules that you stick to or try to avoid when you compose for films?

I always think it’s important to remember that unless you’re talking about diegetic music that’s in the actual environment, there are no rules for what makes sense sonically. In film music there is this historical thing that is reinforced through repetition. People have seen a certain type of music work in the past, so they just feel, This is how you do it. There’s a lot of practicality in filmmaking. It’s not always creative exploration. The other thing I’ll say is that just because you’re using a violin doesn’t mean you have to use a cello, and that doesn’t mean you have to use timpani drums. You can use a violin and a synthesizer and the bagpipes and the sound of a bicycle wheel scraping something. I always have this really wild bouquet of instruments that don’t usually appear together, which hopefully gives it a timeless feeling, a psychological trigger that hasn’t been heard a thousand times.

Christina Hendricks and Ryan Gosling in Drive, dir. Nicolas Winding Refn, 2011

It’s tempting to show the shark, to unveil the alien in music though, isn’t it?

Yeah, but Hitchcock knew better, that there’s nothing more terrifying than what’s in your own brain. It’s stronger not to telegraph the music. I had a conversation with Fien about the murder scene in Home, because originally there was going to be music there and I really wanted there to be no music. To not have it feel like horror. Now, that’s a scene that normally a composer would leap at, to just score up and down because of the drama. But killing someone is hard and it’s awkward. This scene needed to show that they don’t know what they’re doing, they’re kids, that this whole thing is a horrible mistake. And the important thing for me was that it wasn’t to be taken into the musical direction.

When did you learn that self-control?

You know, in the same way in Drive [for which Jewel worked on early compositions, while Cliff Martinez completed the final soundtrack] that I suggested no music for the car chases, which worked out to be very effective. And that’s the thing that you would obviously hit normally as a composer, you know? But the sound design of the engine, done perfectly, is more effective than music could have been. I’ve always thought that the audience is smart. I don’t think you need to spell it out. I definitely feel that the oblique angle is always more effective.

_2048x0.webp)