Inferiority Complex

By Katya Apekina

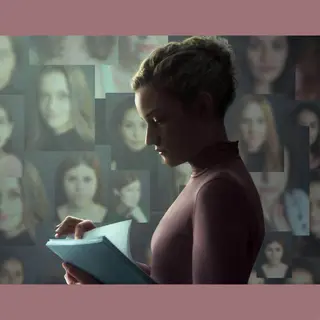

Clouds of Sils Maria, dir. Olivier Assayas, 2014

Inferiority Complex

From All About Eve to Tár, the ambiguities and temptations of being an assistant

By Katya Apekina

March 13, 2024

When I graduated from college, I found a posting on the campus message board from a blind writer looking for an assistant and “amanuensis,” a word I had to look up before my interview. I had literary ambitions myself, and the writer had published many books and was a regular contributor to The New Yorker. (His previous assistant had died when something fell off a scaffold and hit her.) The job entailed reading to him; going on walks with him in his neighborhood, during which he used me as a human plow on the crowded Manhattan sidewalks; and light administrative tasks, like printing out his emails and sending them to the university that housed his archive. “Think of me as your confessor,” he said on one of our walks. “My last assistant told me she had a pierced clitoris.”

From left: Julia Garner and Bregje Heinen in The Assistant; Bette Davis, Gary Merrill and Anne Baxter in All About Eve

I did not feel an urge to make any confessions, but when I look back at emails from this time period I’m surprised to see that I described him as “a sweetie.” I lasted only several weeks in the job before a better opportunity came along, but throughout my twenties I would take many other assistant jobs—to a film producer whose boss is currently in jail for financial crimes, to a filmmaker who remains a good friend, to a chain-smoking literary agent. Short-term, low-paid, His Girl Friday–type stuff. I enjoyed the lack of boundaries and the strange intimacy of these jobs, even though I was not a good assistant, a fact I’m reminded of when I watch movies about assistants, of which there is no short supply.

Onscreen assistant characters do not, as I did, drift along, skirting competence out of a fear that they’d then be stuck having to be competent (God forbid). No, they are eager understudies or subtle puppet masters, using their positions like apprenticeships in which each tedious task somehow brings them closer to the centers of power. Even in Personal Shopper, in which Kristen Stewart’s character openly acknowledges the pointlessness of her work, she still somehow manages to do it well. She isn’t kicking a bunch of packages down the sidewalk toward the post office, or accidentally throwing out mail, or calling in sick because it’s a sunny day outside and the prospect of being indoors seems unbearable.

Tár, dir. Todd Field, 2022

In Kitty Green’s The Assistant (2019), Jane (Julia Garner) works for a Harvey Weinstein–type figure. She’s the first one in the office (arriving when it’s still dark) and the last to leave, subsisting on plastic-wrapped deli muffins for dinner and never seeing daylight. Jane is a striving Northwestern University graduate with dreams of becoming a producer herself. The film, like no other I’ve seen, shows in excruciating detail the tedium and dread of being an assistant. Under the harsh fluorescent lighting of the office, the film grinds out in what feels like real-time Jane xeroxing, Jane tidying, Jane bringing people their lunch, Jane turning on lights, Jane turning off lights, Jane having uncomfortable interactions with her co-workers, Jane transferring her boss’s used erectile-dysfunction syringes from his trash can to a hazardous waste bag. It’s well known in the office that he is using his position of power to coerce women into sex. The horror-movie tone comes as much from the mind-numbing monotony of office work as from the moral question of whether she is implicated in her boss’s bad behavior. As his assistant, what is Jane’s complicity? She’s both supplicant to and agent of this gatekeeper, so what or to whom is her “duty”? She brings a complaint to HR, but this goes nowhere. Nobody else in the office seems to care. When her boss finds out about the complaint, he forces her to write him an apology, which she does. He replies, “You’re good. You’re very good. I’m tough on you because I’m going to make you great.” As she reads the email, Jane blinks back tears, presumably at the humiliation she feels at her own ambition. How disgusting it is that praise, even from a reprehensible source like this, feels so good.

The movie seems to imply that, like everybody else in the office, Jane will take the path of least resistance, turning a blind eye in order to rise through the ranks. But some cinematic mentees, like Francesca (Noémie Merlant), the assistant to predatory symphony conductor Lydia (Cate Blanchett) in Todd Field’s Tár (2022), have the satisfaction of meting out justice. At first, Francesca is the picture of devotion, ready backstage with hand sanitizer and a pill, mouthing along as Lydia’s bio is read aloud by Adam Gopnik—a bio she must have written. She flits around the edges of Lydia’s life, watching from the corner of the mirror as Lydia tries on a tailored suit and hovering as Lydia flirts with admirers after her event. She lingers when dropping off the suit, clearly wanting Lydia to engage with her complete dedication and availability. An aspiring conductor herself, Francesca is the perfect assistant: She seems to have excellent taste and a set of ears that Lydia can rely on, and most important, discretion. Until Lydia passes her over for an assistant conductor position. In a move that shows how access can be weaponized, Francesca resigns in the middle of the night and shares all the damning emails that she has not deleted as instructed (instead having hung onto them as collateral), which confirm the extent and depth of Lydia’s monstrousness and implicate her in a former mentee’s suicide. The scaffolding girding Lydia’s power—embodied by Francesca’s loyalty—was flimsy. She falls hard.

“…They are eager understudies or subtle puppet masters, using their positions like apprenticeships in which each tedious task somehow brings them closer to the centers of power.”

If Francesca is pushed to her betrayal, still other assistants are depicted as being actively conniving from the jump. In the mother of all assistant films, All About Eve, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Eve’s extreme competence allows her to insinuate herself into her boss’s life and make herself indispensable. Margo Channing (Bette Davis) has gone soft in her fame. An aging diva, she’s vulnerable to flattery and to the kind of Machiavellian traps that Eve (Anne Baxter) is setting for her. Eve is assistant as (literal) understudy, the younger, newer model, studying Margo so she can become her. Eve’s mask inevitably slips and we see that she is neither worshipful nor innocent as she steals a role from Margo and attempts to steal Margo’s man as well—but in this arena, at least, she fails. The film ends with Eve, successful and miserable, acquiring an Eve of her own—a high school student, the new generation even more brazen than the last. The final shot of the film is this new girl standing in front of a three-panel mirror, trying on Eve’s clothing, just as Eve had once done to Margo: an infinite succession of assistants, each one coming to replace the next. The silhouette is there for them, cut already to a specific young shape, and the girls are interchangeable, with a built-in shelf life. It’s dehumanizing, of course.

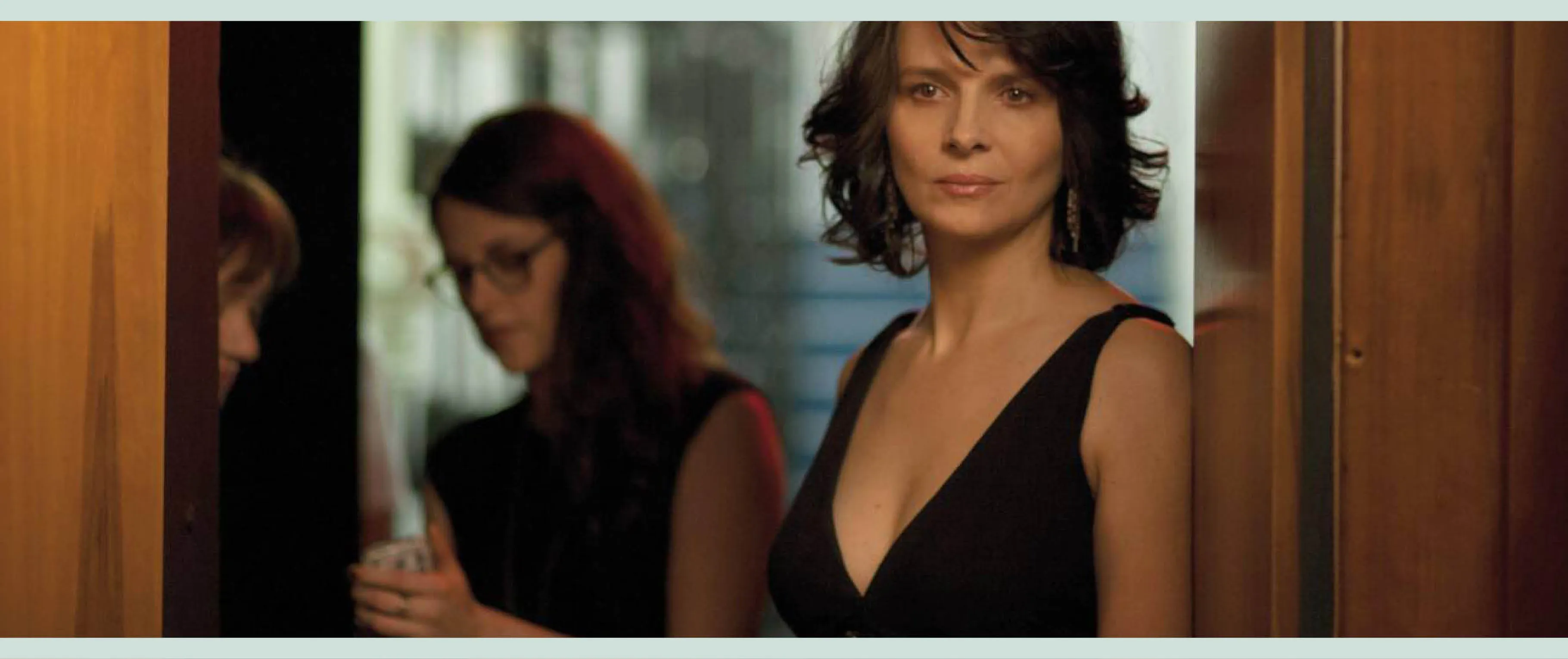

These same anxieties around aging are at the heart of the struggles of Maria Enders (Juliette Binoche) in Olivier Assayas’s 2014 meta-narrative film Clouds of Sils Maria. At the encouragement of her assistant, Valentine (Kristen Stewart), Maria reluctantly returns to the play that had originally propelled her to stardom—only now she assumes the older role instead of the ingenue. The play itself could be seen as an allegory for the assistant-mentor power dynamics: Sigrid is a young woman who seduces and then discards the older Helena. These dynamics also refract and reflect in the relationship between actor and assistant. Valentine is neither sycophant nor understudy to Maria but consigliere and orchestrator, the one who sets up the meeting with the director and who persuades Maria to take a part she finds humiliating. As with the characters in the play, there’s a sexual undercurrent between the two of them, and Valentine seems aware of but not too troubled by Maria’s desire for her, which is then mirrored when Valentine helps run lines for the play. Their relationship blurs with that of the characters’ dynamic, and their fighting and resentment escalate. At one point, during an argument, Maria shouts for her cigarettes, which Valentine points out are right in front of her. “Where?” Maria can’t seem to see them. Valentine gets up and fetches them for her. It’s a barely-there diva moment, an assertion of who has the power—ostensibly Maria, since she’s demanding to be served, but in this she is also forfeiting her competence and agency. She is helpless without Valentine, literally unable to see what is directly in front of her. Ultimately Valentine, fed up with the emotional burden of having to buttress Maria’s ego, walks off from their hike into the foggy Alps, never to be seen again. Mic drop. No mealy-mouthed emails full of excuses and justifications. It’s the sort of departure I could have only dreamed of.

From left: Kristen Stewart in Personal Shopper; Julia Garner in The Assistant

Two years after Clouds of Sils Maria, Kristen Stewart reunited with Olivier Assayas for Personal Shopper, in which she plays Maureen, also an assistant, this time to an influencer she openly disdains. Maureen is doing the job for money, not for love—staying in Paris because her twin brother died there and she is awaiting contact from his ghost. As in All About Eve, she samples the identity of the woman she’s serving, trying on her boss’s clothes, confiding in her boss’s boyfriend. It’s a passive form of dominance, or at least revenge, to steal these things from the woman who seems to have everything. When Maureen finds her boss brutally murdered, it feels like a metaphysical manifestation of Maureen’s covetousness.

The role of assistant invites such covetousness. In these poorly paid supporting positions, the real compensation is in the dangled promise that the boss’s success, power, connections or talent will one day be yours. But it’s strange to think that an apprenticeship model would apply here. How can absorbing the tedious and menial details of someone else’s life leave enough space for you to create anything of your own? How could it possibly prepare you to step into their shoes and assume their artistic mantle?

In retrospect I probably could have been a very good assistant. I was eager to please and capable of being capable. But a professor once told me that she had specifically never learned to type so that the men in her department wouldn’t delegate the secretarial work to her. This made sense to me as a strategy to ensure that I got to do the kind of work I cared about. If I did everything else badly, I wouldn’t have to do it. Not for very long, anyway.