In Defense of Silence

By Tim Griffin

La Dolce Vita, dir. Federico Fellini, 1960

In Defense of Silence

The cinematic performances that speak the loudest don’t require any words at all

By Tim Griffin

November 8, 2023

Marlon Brando once said that the crucial difference between acting on stage and on camera could be encapsulated in this dramaturgical advice: In cinema, do as little as possible. In other words, a great screen actor is someone who might seek to convey emotions—whether through gesture or facial expression—but is often much better off being the receiver of them. The performer should provide a cool presence onto which audiences project their own feelings, and those feelings are, Brando argued, bound to animate characters more powerfully than any actor could hope.

In the Mood for Love, dir. Wong Kar-wai, 2000

Such a proposition certainly goes some way toward explaining why a whole generation of actors fell by the wayside during the late 1920s, after the revolutionary arrival of such “talkies” as the blockbuster movie The Jazz Singer (1927). From then on, the embroidered physical vocabulary of dramatic expressions and gestures necessary to silent film went the way of Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (1950). The loud body language so essential for those movies was displaced by the spoken word.

Nevertheless, Brando’s adage prompts the question of whether silence retains a special, if subtler, place in cinema today. Amid all the technological advancements in sound design, the onslaught to the ears of blockbuster action films, and the hysterics of today’s melodramas, a case can be made that a vital source of film’s magic resides precisely in its silences. Consider one of the most stirring scenes in director Sian Heder’s dramatic comedy CODA (2021), when a young singer invites her deaf parents to a school concert, and the film presents her performance as the parents would experience it: in absolute silence, which only heightens their awareness of the visceral pleasure being felt by those audience members who hear it. Or think of Tilda Swinton’s rock star in A Bigger Splash (2015), whose vocal cord surgery leaves her without a voice, magnifying a sense of isolation to her character—rendering her visage just one more surface amid a sea of visual opulence in a film named, and styled, after a famously glamorous yet deadpan David Hockney painting.

Five Easy Pieces, dir. Bob Rafelson, 1970

Some of the most important films of the past century revolve around such highly orchestrated moments, when all the dialogue and noise shuts off. In Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), the very rise of cinema—and of our contemporary media landscape—is attended by a loss of language. Even the personal history of the film’s protagonist, Marcello, mirrors this cultural devolution. As the charming but conflicted writer drunkenly recounts at a party, he started out as an author before setting aside literature for journalism, which he has finally given up for a job in publicity: the management of images. If La Dolce Vita is frequently considered Fellini’s rendition of Dante’s Inferno—the work takes its name from a phrase in the epic poem—its descent through the circles of Hell is not only a matter of traversing Rome’s decadent social spheres, but also a tale of words losing their utility until communication has become utterly impossible.

La Dolce Vita’s most illuminating “circle” of Hades can be found at the film’s ending: Sitting on a beach after an all-night celebration, Marcello sees a young woman—whom he’d met earlier at a café, comparing her to an angel from an Umbrian church—gesturing toward him across a small inlet. But as she tries to speak, he cannot hear her against the sound of the wind and crashing waves, and neither can his words reach her. This finally prompts him to shrug and walk wistfully away. And at that juncture—in one of the most famous endings in 20th-century cinema—the young woman’s eyes follow the protagonist before looking directly at the camera, breaking the fourth wall. No characters are “expressing” anything. The only words to be heard by audience members are those forming (or being searched for) inside their own heads.

Marcello Mastroianni in La Dolce Vita

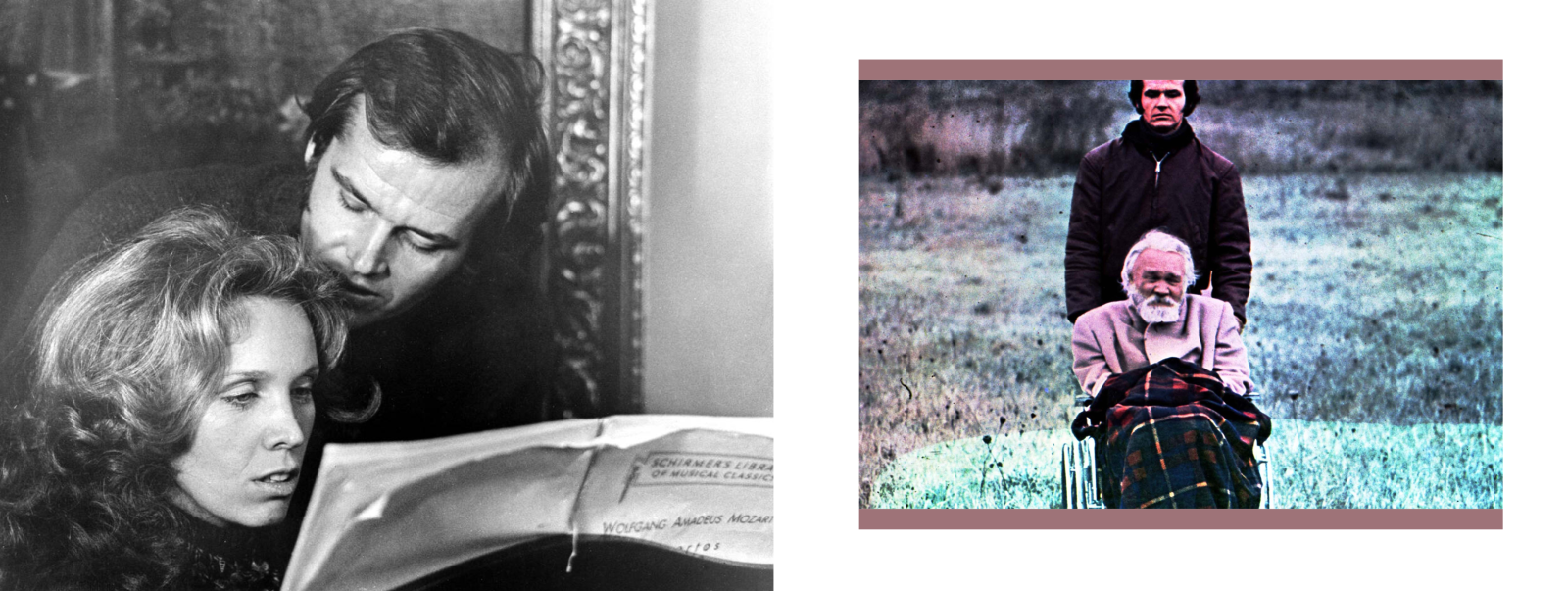

The implications of this conundrum become clearer when considered alongside another famous moment of silence, in the Bob Rafelson’s classic Five Easy Pieces (1970), in which a disaffected classical pianist—who has abandoned both a promising career and his prominent family’s legacy in the arts—briefly returns home to see his estranged father. In one of the movie’s final passages, the pianist, played by Jack Nicholson, takes the patriarch’s wheelchair to the shore (a recent pair of strokes has left the father unable to talk) and kneels beside him. Ostensibly, Nicholson’s character is seeking to connect with his dying father. But the scene unfolds in a way that instead asks whether people in conversation are ultimately just talking to themselves: When speaking in dialogue, to what extent do we merely put ourselves in conversation with whatever it is that we are projecting onto others? The filial discussion in Five Easy Pieces turns out to be pure monologue for Nicholson, during which the father’s wordless visage appears in close-ups that possess all the blankness of screen tests, until the son admits that he finds himself “trying to imagine your half of this conversation.” Wanting to communicate and receiving only silence, Nicholson’s character is faced with his own, ultimately unresolved desire to find a genuine connection between the words he’s saying and the feelings being stirred within.

In some ways, it’s a conundrum that also cuts to the very core of art-making and watching—or so Five Easy Pieces pointedly suggests in an earlier scene, in which Nicholson plays Frédéric Chopin’s Prelude in E Minor to a houseguest (Susan Anspach). When Anspach’s character says she is deeply moved by his “inner feeling,” he cynically replies that he has none at all—prompting her to say curtly that she “must have been supplying it.” Here again, the performer’s failure, or incapacity, to express himself—a kind of emotive silence—leaves an audience member filling in the gap.

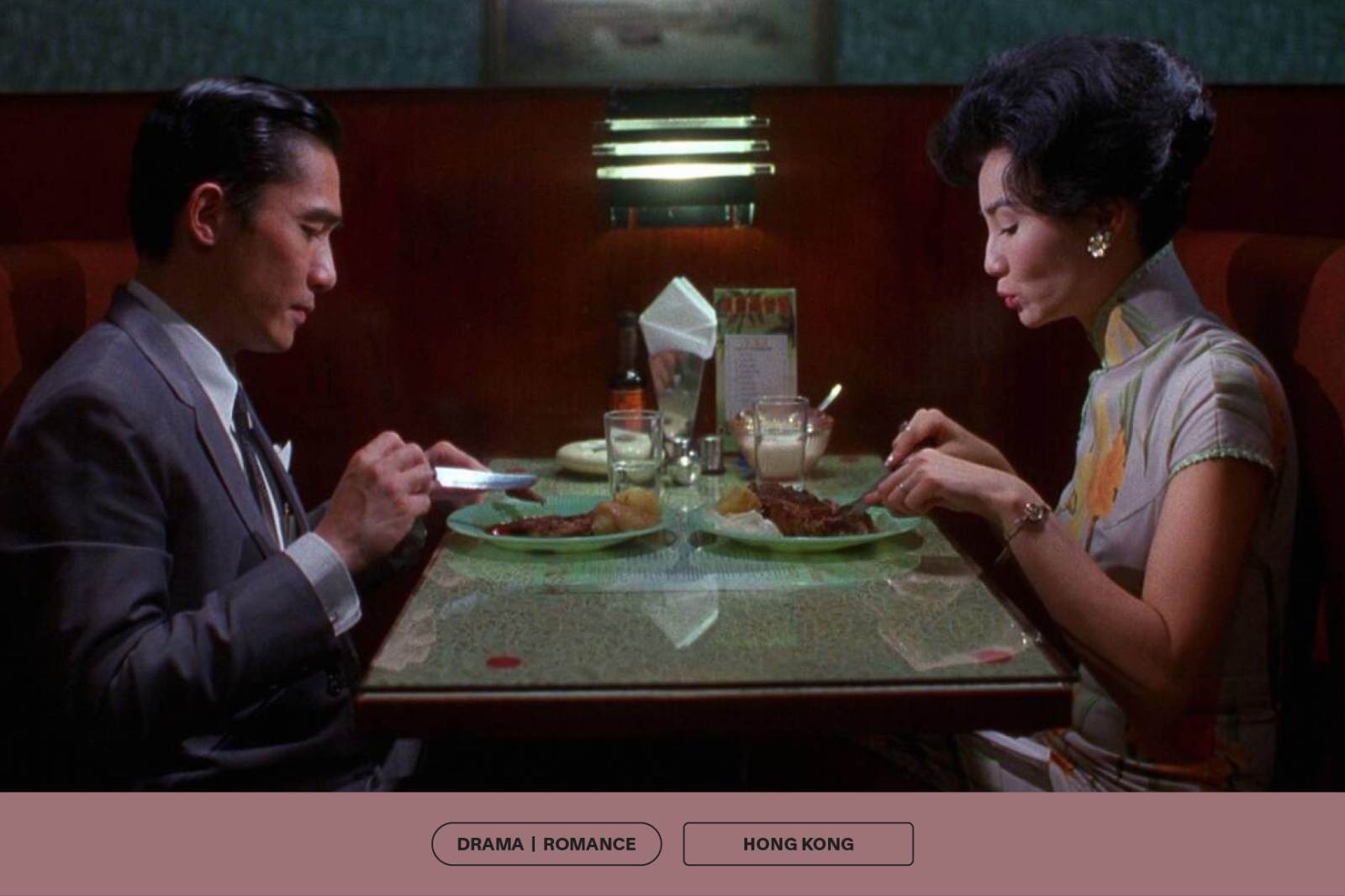

Yet no contemporary film takes up this question of outward facade and interior emotion as brilliantly as Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), in which two neighbors, Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung Chiu-wai) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung), discover that their respective spouses are having an affair—forcing the duo to come to grips with how much of their lives are both driven by appearances and scripted by social convention. Most of the film’s opening scenes comprise decorous introductions among characters, underlining how even in daily life we often function like characters in the world, each of us playing a role with the use of a set script. Time and again, people—from landlords to business partners, and even Chow and Su—ask each other not just their names, but also for their place on the social stage: “How should I address you?” Herein lies a certain irony: They ask for words with which they may describe one another, but only while suggesting that such definitions are superficial, just describing the surfaces of a social sphere. Their answers don’t reflect the real person hidden beneath.

This superficial landscape—and the sense of the protagonists being at odds with it—pervades much of this masterful film. As the pair takes solace in each other’s company, they become increasingly aware of how their habits invite misunderstandings by their neighbors, who are bound to contemplate and interpret their actions. As Su observes matter-of-factly, suggesting how appearances have a language of their own, “You notice things if you pay attention.” Such mind games surrounding cultural narrative and performance eventually become interwoven with Wong Kar-wai’s own storytelling: Su and Chow begin playacting confrontations with their spouses—and even begin rehearsing the end of their own friendship—so that we are often uncertain, at first glance, whether the conversations are genuine or being staged. This ambiguity prompts deeper reflection: How can anyone truly know the person with whom one speaks? To what extent is language a mediating veil between us, which can never be parted?

Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung Chiu-wai in In the Mood for Love

Chow himself seems to struggle with something akin to this when, eating a meal with a friend, he recounts how “in the old days, if someone had a secret they didn’t want to share…they went up a mountain, found a tree, carved a hole in it and whispered the secret into the hole. Then they covered it with mud.” We assume that his ruminations are inspired by an unspoken love for Su, which has built up over their time together yet has gone unfulfilled precisely because social convention makes it impermissible. Such a longing must remain a secret, always hidden and forever at odds with public appearances. This solitary action on the mountain—expressing oneself in private to an impassive object in nature—would offer some modicum of relief.

Another possible reading of this legend, however, is that words can never describe or capture such love—and that allowing it to remain unspoken and unheard is a way not only for Chow to honor it but also for the director Wong Kar-wai to memorialize it. An art form like cinema, by its nature, creates meaning in the spaces between what is said and unsaid onscreen; between what is seen, and then thought, by audiences. At the end of In the Mood for Love, Chow visits the ruins of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, whispering into a wall and sealing it with mud. We see his actions but never hear what was said, left with our own imaginings of his possible words. Wong Kar-wai’s camera passes across the impassive, mythic surfaces of the temple, with this story becoming just one among so many others commemorated in art—the cinematic beauty arising in its being ambiguous, unresolved and rendered as silent as stone.