Getting Lucid with Richard Linklater

By Josh Siegel

Boyhood, dir. Richard Linklater, 2014

Getting Lucid with Richard Linklater

Theories on memory, time and dreaming from cinema’s leading chronologist

By Josh Siegel

February 3, 2024

Richard Linklater at the BFI London Film Festival, 2023

Richard Linklater is cinema’s greatest practitioner of what might be called the longitudinal film. A term borrowed from science, longitudinal studies explore the ways in which characters change across time under a set of closely observed conditions. Linklater has traced the birth, life, death and postmortem of a love affair in his Before trilogy (Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight); the formative years of a brother and sister between the ages of 6 (and 8) and 18 (and 20) in Boyhood; suburban teenage life across several films including Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Everybody Wants Some!!, SubUrbia and Tape. His current project in development, a wildly ambitious screen adaptation of Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along, is going to take the next 20 years to film, in keeping with the reverse chronological structure of the musical. In all of these cases, Linklater has made subjective experience and the relativity of time central to his work.

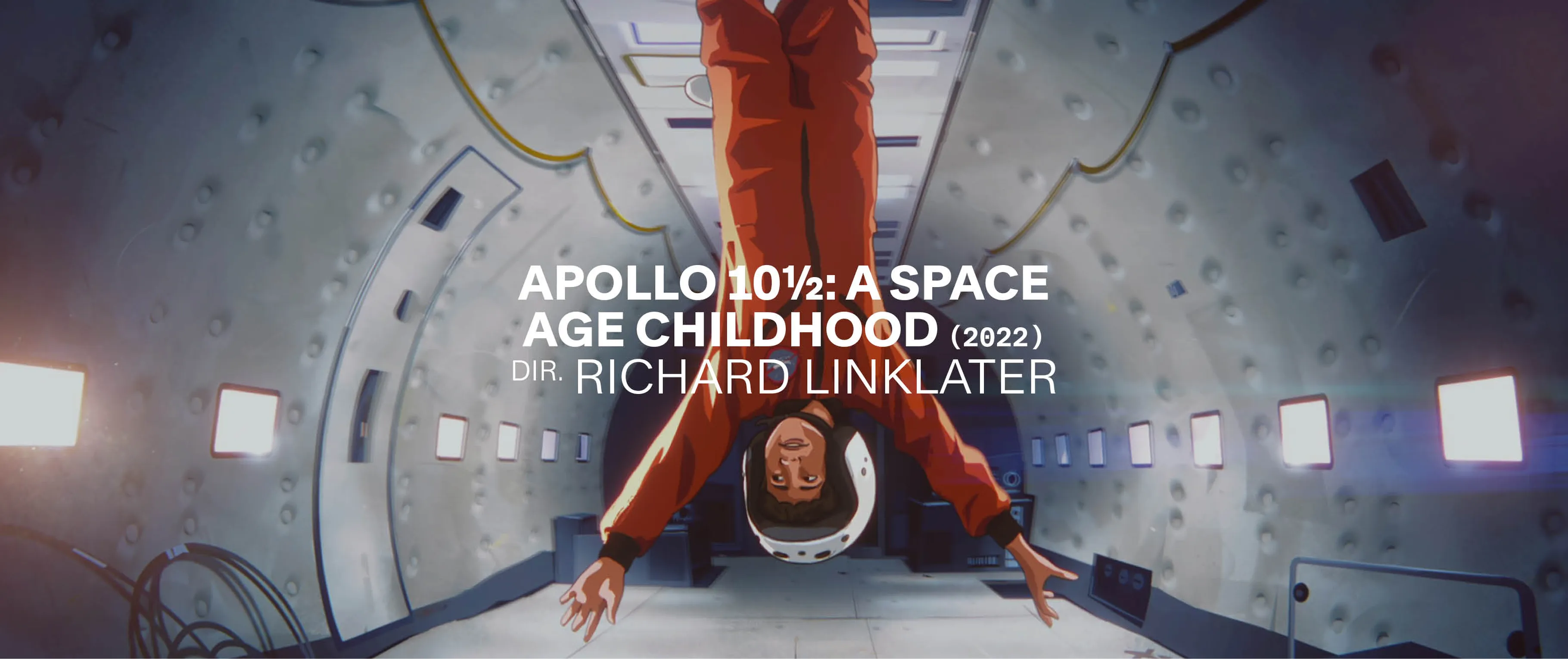

In this conversation with Galerie, spurred by Linklater’s 2022 film Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, the writer-director meditates on many of the big themes that have fascinated him throughout his career: the chance encounter and the (in)decisive moment, the slipperiness of perception and memory, and the perils of nostalgia, with witty observations about Leo Tolstoy, Stanley Kubrick and Vanessa Redgrave along the way. Not long ago, The New Yorker offered a revisionist take on baby boomers titled “The ‘Dazed and Confused’ Generation” (how quickly we seem to forget that Generation X was also known as the Slacker Generation). It’s all a measure of Linklater’s enduring influence on the cultural zeitgeist. But his work also belongs to a larger modernist enterprise of genre-bending experiments in form, altered states of consciousness, and a playful blurring of the staged and the unmediated. This occupation with identity and epistemological uncertainty extends to his most recent movie, Hit Man, a comic character study in chameleonic shape-shifting co-written by and starring Glen Powell, who plays real-life Gary Johnson, a philosophy professor moonlighting as a fake contract killer to help the local police. As Linklater himself describes his films, they work as “flowing time sculptures.”

From left: Waking Life, dir. Richard Linklater, 2001; Before Sunset, dir. Richard Linklater, 2004

In 2019 I did a retrospective at MoMA [Museum of Modern Art, New York] with the great screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière. Jean-Claude told me that whenever he sat down to write with Luis Buñuel, in order to get their imaginative juices flowing, they would share their dreams from the night before. This might be a fun way for us to limber up for our conversation, Rick. Do you remember what you dreamed last night?

Obviously I dreamed. I had to get up in the night to pee, so that’s when it’s always kind of vibrant. But now I don’t remember the dream. My dream-journal and lucid-dreaming days were pretty specific to one film I made way back.

Waking Life. I’ve always wanted to ask you if you’re capable of lucid dreaming.

Oh yeah. I was a natural lucid dreamer. I’ve had that phenomenon in my life for a long time. With that movie I said, “Okay, I’m going to sit down and really try to understand this from a brain-science angle.” So I met with scientists. I felt like I got a Master’s in Lucid Dreaming, and I included a lot of that in the movie. It’s almost a how-to instruction manual if you care to use it that way. I learned anyone can do it, but some people have more of a natural proclivity. But it’s a discipline, just like meditation. The joy and crazy aspect of Waking Life was that I dreamed lucidly every night of that whole shoot. I couldn’t tell my waking life from my dreams, it all just blended together during the making of that movie. It was really fascinating.

You’re less inclined to lucid dream now?

Yeah. But I did find it pretty creative. When you become lucid, you’re always on the verge of waking up because you know you’re dreaming. You’re much closer to the surface. The thing is to remain calm and go with it. Then you can fly around and do stuff.

I always find I’m a math genius in my dreams, breezily figuring out impossible formulas.

I’m a great songwriter. Beautiful songs are coming out of me and then I wake up and I’m like, “Wait, I don’t have that skill at all.”

The Burt Bacharach of dreamers. In your film Apollo 10½, there’s a scene in which Stan is lying on a beach blanket staring up at the sky. A similar image opens Boyhood, with Chris Martin of Coldplay singing, “Look at the stars, look how they shine for you.” And it can also be found in Waking Life, when the main character gazes up at a shooting star and suddenly floats in a most peculiar way. What is it about this image that’s stayed with you?

I think I had those kinds of lucid dreams as a little kid. I remember floating off and being pulled heavenward. I also remember thinking, like, Oh, if I let go, I’m going to float, and I’m not ready to leave this world just yet.

When you describe the newness of the Astrodome in Apollo 10½, I’m put in mind of Brewster McCloud (1970) and the fantasy of being able to fly. That Robert Altman film also has the Icarus myth attached to it, along with its sense of danger.

I love that film, and not just because of the Astrodome. I always heard that film was one of Altman’s favorites.

Did you do research at NASA for the film where you got to experience an antigravity environment?

I did a lot of research and visited NASA regularly but no, I didn’t get astronaut training. I didn’t feel like I had to. When I make a film, I don’t need to have the experience myself. And I’m the opposite of an adrenaline junkie, riding roller coasters, jumping out of airplanes. I’m like, “Nah.”

Yet speaking of flight, didn’t you make a Super 8 movie early in your career where you threw cameras off the side of a mountain?

Yeah. And in Waking Life, when he first leaves his body and we’re floating up, that’s me hanging out of a hot-air balloon. What amazed me about being in a balloon, unlike planes or helicopters, is that it’s silent. There’s no roar of engines, like you’re truly a bird flying. Every now and then there’s a blast of helium to keep it going. I was leaning out the side. I’ve leaned out of a few helicopters, too.

So much for not being a daredevil.

At the end of the day you’re just kind of obsessed with the shot you’re trying to get. And then you look up and go, “Oh, this is amazing.”

The documentarian Jean Rouch once said that film has the power to reveal “a fictional part of all of us, which for me is the most real part of an individual.” This reminds me of something you’ve said, that “our true lifetime relationship is with our younger selves.” In your work there’s this constant attempt to understand that younger self as if it’s something apart from you.

I’ve found that very cathartic. That’s all that ever really motivated me, and I’ve been lucky to be able to explore little moments in my own past. And I try to make a fun, entertaining film around that. But I’m definitely dealing with moments in my own history. Even with the Before films, I did meet a young woman and we did spend a night together. I’m always dealing with what’s in front of me and what’s lingering in my own memory. And I think directors and any natural storyteller tend to see the world metaphorically, like, “What does it mean? Yeah, this is what’s happening, but what’s the deeper significance of it?” I was always cursed with that. It kind of makes you a third person to your own life, a little bit like you’re seeing the world through a window.

You first saw the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey when you were about 7 years old, right? That movie means something very different to a 7-year-old than it would to an 80-year-old. I wonder what your impressions of that film were as a kid.

That’s the absolute genius of that film. That’s why it’ll perennially be up there as one of the greats of all time, because I marvel at how much that blew my mind and intrigued me as a 7-year-old and how much it still does, but always on a slightly different level. You pick up the humor or contemplate life on another planet. Kubrick’s films work on some nonintellectual level. It’s like a direct line into your consciousness.

In Apollo 10½ you have the kid trying to explain the meaning of that film to anyone who will listen.

That scene is 100 percent autobiographical. I can still see the kid’s face as I was losing my audience explaining the movie.

I think I first saw it at the same age, roughly 7, but sadly on my grandparents’ black-and-white television. No color, no widescreen expanse.

I probably saw 2001 in 70mm on its first run. The screens were huge back then in certain theaters, so I got the full 70mm experience. But I saw The Wizard of Oz on a shitty black-and-white TV. I probably didn’t see the color version until I was a teenager.

Do you have any home movies of you as a child?

They’re sporadic and usually taken by grandparents. It’s really interesting the way home movies become your memories. I remember sitting on one of those inflatable pools, but it’s like, “No, you don’t. You remember watching the movie of you doing that.”

Is it fair to say that a lot of your films are home movies of a sort? Boyhood is a home movie.

Fair enough. Certainly Dazed and Confused, Everybody Wants Some!!, the Befores. Obviously every film is personal to every director. I’m thinking the first thing I did that originated outside me was [Eric] Bogosian’s SubUrbia. But I was still thinking, like, Oh, that’s my own movie of that era in my life. The hanging out, the early twenties version that I sort of knew, it was something personal that I felt like I adapted. Personal comes from a lot of different directions, but I’m one of the few who admits autobiography. Everybody else is like, “Oh no. That’s not from my life.” But I always admit it as a jumping off point. It’s just always made sense to me to work from that spot.

Do you think that’s why you started making films?

I just loved movies and I had some grand ideas. As a teenager I wrote a lot of short stories that were science-fictiony, fantastic. In my head I could have been Steven Spielberg, but once I really got down to it I was like, “No. It’s much more close to home.” I think my teenage self would be surprised if he learned that “Oh, you’re going to make films someday.” I probably would’ve thought I’d do something a little crazier.

From left: Waking Life; Ellar Coltrane in Boyhood

Do you think that books have inspired your filmmaking?

Books were a huge deal growing up, especially for my mom. We had a reading time. “No more TV, you’re going in your room, you’re reading.” We read every day. I’m the least educated person in my family. Even the women in my family, like my grandmothers, were teachers. But my mom kind of did it backwards. She had kids first, like a good Catholic girl. She turned 23 two weeks after having me, and I was her third kid. Crazy. Then she went back to college. I saw her work her way up from student to college teacher.

There’s a shot in Apollo 10½ of your surrogate mom typing at the dining table, right? The sense of a life beyond the confines of her suburban home, a life that could be found in books. Was there any kind of literary analog to the narrative cinema you wanted to make?

I liked Tolstoy’s view of history, the way he would take something grand but then bring it to such a personal, granular scale. He had the real minimal within the grand. War and Peace is really just these people passing through and flirting with the washerwoman.

Did you have a View-Master growing up?

Sure. Those were pretty prevalent.

I ask because there’s a certain View-Master vision of American suburban life that you’re presenting in Apollo 10½. Tellingly, you consign the problems of the world largely to the television set: the race riots, the assassinations, the war in a country in faraway Southeast Asia.

That’s how the suburbs were designed, to hide away everything troubling. It ultimately failed when they had their own “Here come all the human problems like teenage drug use.”

I was thinking of the TV interview you include in Apollo 10½ of the Black guy on the street talking about poverty in the slums. And of course Gil Scott-Heron’s devastating spoken-word poem “Whitey on the Moon” comes to mind. Did you have any sense growing up of what was going on, or were you completely oblivious?

I was oblivious, but I was just too young. I certainly knew hippies and Black Power people. They permeated the University of Houston, so that was always intriguing. I’m the kid looking out the car window going, “Wow, look at that.” But as far as the politics of it, no, I didn’t really get that until a few years later. I mean, you can’t miss the politics of it when you see race riots on TV and Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, things that were all around but that feel far away. It’s just on the TV.

I see a level of patience being portrayed in Apollo 10½ as well. People glued to their TVs had to wait three days between the takeoff and the moon landing, right? There was no immediate gratification. When today do we ever feel that combination of nervous anticipation, stress, boredom, joy and release? Boredom is wonderful. The moment where you have everyone drifting off to sleep because they’re exhausted, right? It’s perfect, because your memory of the experience is going to be very different from your experience itself, where you were passed out on the couch.

When I was a kid, I saw the moon landing. I was there, I was sitting there, but then to be honest with myself, it’s like, no, I fell asleep because I was exhausted from going to AstroWorld all day, and it was late and we were waiting and waiting and waiting.

Richard Linklater filming Before Sunset

The waiting is something you don’t have to do anymore. That’s lost.

Staring at the test pattern, waiting for the first cartoon to come on on Saturday morning. That was anticipation. When the test pattern went away, you knew the good stuff was coming. That was fun.

Something really important in your films is an acknowledgement of how different people experience events, however mundane or momentous. It can even be associative. When you describe the disastrous explosion of the first Apollo Saturn mission, it made me remember the Skylab crashing to Earth when I was young, or the Challenger exploding. These are key formative moments, and your films try not to reenact but to somehow create the setting in which you experienced them.

My dad talks about being in a car as a kid and they hear over the radio that the Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor, and his father and uncle were just kind of going crazy in the front seat. They were really excited because they knew we had all these great weapons, we were going to just wipe everything out. Every generation has one of those memories—Kennedy, John Lennon.

Where were you when you found out about John Lennon?

I was in my room sophomore year of college. A guy poked his head in and said, “You know who got shot tonight? John Lennon.” Because they were watching Monday Night Football in the other house. We had these two houses, as seen in Everybody Wants Some!! I was in my room, reading, and it was just shocking. Those imprinted memories of where you were when something had happened is a fascinating psychological phenomenon. I’m kind of obsessed with it. There was a psychology teacher who was studying this very subject in the ’80s. When the Challenger disaster happened, he had his whole class write up a memoir of that event. Where were you? Who was there? How did you learn about it? What was your reaction? How it happened in real time. Then he waits, I think, 20 years, and he gets back in touch with all the students and says, “Write me an essay of how you remember that day.” Some were pretty accurate, but a high percentage, like 70 percent, were wildly different even from the other people who were there. But that’s what interests me, how invested we are in our current memory. All memory is a restaging of a previous memory, of a previous memory of an event. You’ve restaged that. It’s not a video you’re rewinding, it’s [that] you’re restaging the event every time you remember it. Maybe a new character shows up, maybe there’s a costume change, you’re in a new location, on a new set. It happens. That’s why eyewitness testimony really shouldn’t be allowed in court. The most fascinating thing about that study is that when they were handed their essay from 20 years ago, a lot of the students went, “Well, I was wrong then.” They didn’t believe what they had written 20 years ago right after the event. They thought they were wrong then, not now.

That’s astonishing.

So invested are they in their memory now that they can’t go, “Oh, I guess I have a bad memory.”

It must be a survival mechanism.

We’re so sure of ourselves. But we should know our strengths and weaknesses. I actually do have a pretty strong visual memory. I freak people out with mine.

“It kind of makes you a third person to your own life, a little bit like you’re seeing the world through a window.”

Really?

I wasn’t a good student. I can’t read the science chapter and recall it the next day. That’s not my thing, but like a conversation—I’ll run into someone I haven’t seen in 30 years, and they’ll barely even remember me, and I’ll go, “Oh, you remember we were outside the hospital your dad was in, he was getting his kidney operated on and we talked about…” I’ll tell him exactly what we talked about, what was going on, the time of year, the weather. Once I met a guy in L.A., he’s a stunt coordinator and he does football movies mostly. He’s kind of a jock. He was introduced to me like, “Oh, here’s Alan. He played for USC back in the ’70s, one of those good teams.” And I was looking at him, and I go, “Were you on The Dating Game? You didn’t win, but you should have. You sang a song.”

You remembered that from his face?

Yeah, his name and his face and that he played for USC. I freaked him out. He says, “Yeah, I sang ‘Peggy Sue.’”

I have a tendency just to appropriate other people’s memories as if they were my own. I have a friend I’ve known since the womb, and I’ll relate a story to her about something that happened to me as a kid, and she’s like, “What are you talking about? That happened to me, not you.”

It’s like looking at the home movie and that becomes your memory. But are we not all sharing a cultural memory? I think that’s closer to what we were talking about, memories of assassinations and big things. They’re these group memories, like societies have memories based on images and coverage that we all receive.

More shared memories.

Yes, it used to be more shared. And now it’s very fractured. Was it propaganda to begin with? Maybe some of it was, but it was one memory. Now we’re all living in the same world, but we’re having very different memories of events filtered through different perspectives, or just not experiencing things at all if they don’t hit your bubble. It’s amazing how we’re all in our own little silos these days. Sadly, you look at the Oscars this year. Best films, best performances, we used to all be on the same page because everybody knew the movies. Now it’s like, Wait, what is this? We’re really fractured. It’s hit the arts. There’s no communal anything. Everyone’s watching something different.

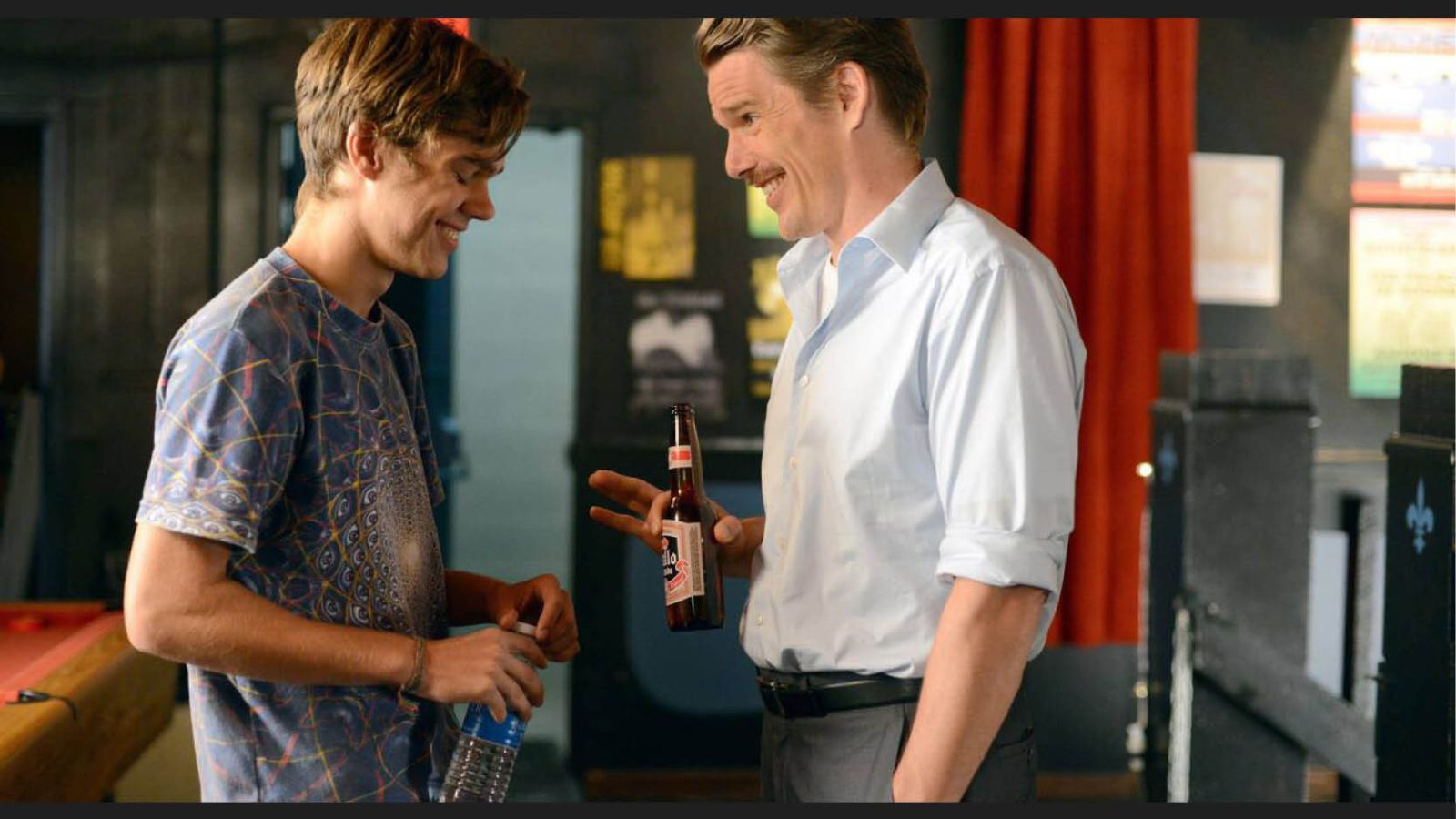

Ellar Coltrane (left) and Ethan Hawke in Boyhood

I know you had a moment where you thought maybe you were going to be a playwright, but did you ever think about directing theater? I feel like you’d be fascinated by the idea that no two performances are ever the same.

I’m enough of a control freak. That might bother me, maybe.

Because when I think of your heroes, like Mike Leigh and Mike Nichols and Bergman, they all moved between film and stage effortlessly, even though it was a totally different muscle to exercise.

I know, I should loosen myself up. I think I’m slowly getting there. I’ve had actors say, “Rick, do theater. You love to rehearse. That’s all it is. You rehearse and you put it on.” I just think too cinematically, maybe. I would have to let it go at some point. I like getting the performance just right, and then you use that take in the movie. But the idea of variation of every performance…. I have enjoyed going to see a play multiple times. It’s always a little different.

That doesn’t appeal to you?

It definitely appeals to me as an audience member. Did you see Long Day’s Journey into Night a long time ago with Vanessa Redgrave, Robert Sean Leonard and Phil Hoffman? I’m friends with Robert Sean Leonard, right? So after the first time I saw it, he was talking about Vanessa, how she didn’t really take directions. I said, “Now, that thing that she did tonight, she just came over and slapped you. She does that every performance? How much did you rehearse it?” He goes, “No, this is the first time she’s ever done that.”

That’s jazz improv. You have to know the structure of the music. You have to anticipate the modulations, the allusions, the motifs, and if you can’t keep up, you’re screwed. That idea of improv in film has never appealed to you?

I think that’s a great actor’s thing. For a director, I’m not so sure. I don’t know how expressive that is for me. I’m not an improv guy. I workshop more than improv. But I always start from the written word. Whereas Mike Leigh actually starts with characters, and I think he’s picking and choosing and writing through them in a certain way with his own ideas.

I think for improv you certainly need a company of actors, an ensemble that you know that you can trust and that you work with repeatedly.

I love film because you can always do another take in your quest for perfection. You can pull back and get it right. You may have other factors that are driving you crazy. The sun’s going down, we don’t have the right piece of equipment. I mean, there’s all these variables that are also making it difficult but you can perfect. So while I studied theater and wrote some plays and was attracted to it, I think film hit my constructive nerve. I like building things, and it seemed more constructed. I appreciated the craft of it.

I’m risking a Sondheim question—a project you’ve been working on for a while—but when did the idea of a longitudinal film come to you? I think of specific films like the Before series and Boyhood and now Merrily We Roll Along as longitudinal studies, one of your most profound contributions to cinema.

A Harvard men’s study, from 1923 on. I love a longitudinal science study.

Is there any precedent in film in your mind?

Other than documentaries, like [Michael Apted’s] Up series, I haven’t seen it in narrative. Some of Steve James’s things go over years. I was also struck by one of Éric Rohmer’s films, where Marie Rivière is in one film in the 1980s, sitting on a bus, and several years later, there she is again in A Tale of Winter. And when I saw her, I just realized how she had aged. It just struck me as like, Oh wow, what an interesting thing time does, and that’s me putting it together in my head. I like the way people age on film.

François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films are perhaps another precedent, another New Wave example. I don’t think Truffaut imagined making more films about the character when he set out to make The 400 Blows and Love at Twenty.

For The 400 Blows, I don’t think he had a plan. I didn’t have a plan on the Befores. We didn’t talk about future films. And I think with Truffaut, that Love at Twenty just sort of came up, it was financed and he’s like, “Oh, why don’t I get back with Jean-Pierre Léaud and we'll just take that character.” And then time goes by and you realize you’re making a life project that articulates phases of life.

You’ve raised the stakes with Merrily We Roll Along.

Steve [Sondheim] loved the idea of doing Merrily over time, and he was so receptive. I mean, it was immediate. When he was asked, his immediate response was “Although I won’t be around to see the finished product, I think it’s a great idea. You should do it.” Boyhood was different. Boyhood was like a darkroom with the pictures slowly coming into focus, his maturity so gradual. That happened to me as I was sitting down to write. I think in almost scientific terms. I hit a wall with my thinking about my childhood movie because I was confronted with this limitation. Do you know the Jean Eustache film My Little Loves?

That’s one of my favorite films.

I love that movie. But the women are getting older and the main character is staying the same. By the end he’s escorting a girl who looks so much more mature, and you just think, You’re too young to be doing that, you’re still the little kid. I had that in mind for Boyhood. But I’m asking 7 to 18, which is a longer time frame than My Little Loves. In film, you’re stuck with this age dilemma. Do you just cast someone else at a different age? That’s the time worm. But then I realized I had little things I wanted to portray over the years. There wasn’t a big gap in the story I wanted to tell. So I had kind of given up the idea of the film altogether. I was sitting down to write the experimental novel floating around in my head, returning to my teenage ambition, pre-film. This is a couple months of really thinking about this problem, taking it to bed with me, having given up on it. The fingers hit the keyboards and this idea just goes off in my head, like a little pop. I was like, Wait a second. What if they just gradually got older and I covered those years? I just saw the whole movie in my head. That’s the good news. The bad news is that it’s going to take 12 years! But so much, I think, about filmmaking and the arts in general is problem-solving.