From Russia With Love of Film

By Katya Apekina

Kira Kovalenko and Kantemir Balagov at the Telluride Film Festival, 2022

FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE FOR FILM

Exploring transitional states with intrepid auteurs Kira Kovalenko and Kantemir Balagov

Katya Apekina

July 5, 2023

After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the dissident filmmakers Kira Kovalenko and Kantemir Balagov took to the streets and to social media to protest, but things quickly began to feel dangerous. The consequences for speaking out against the invasion have been extreme—up to 15 years in prison. The duo, whose films have previously been Oscar submissions for Best International Feature by their native country, currently reside in Los Angeles with their Italian greyhound Rocco, also an emigré. Taking a stand has cost them, and yet what other path was there for two artists who see the world with such honest clarity?

When we met, Balagov was thoughtful as he sat discussing the uncertainty of their predicament. Dressed in a The North Face x Gucci T- shirt and Balenciaga cap, he could have walked straight off the L train in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and yet had the caution of someone uncomfortably in limbo. Kovalenko sat beside him with Rocco shivering in her lap. She has blunt orange bangs and an equally hip sense of style, but most striking is her direct and attentive gaze, which seems to see all people and situations in their full complexity. Her film Unclenching the Fists (2021), set in a small mining town in North Ossetia, Russia, won Cannes’s Un Certain Regard grand prize. It’s the story of a young woman who, as a child, survived the Beslan school siege and now has the literal scars of the Russian-Chechen conflict on her body. Her controlling father won’t let her get the medical help she needs, and so she’s forced to take drastic action—her freedom coming at an impossible price.

In Balagov’s first feature film, Closeness (2017), which won a FIPRESCI prize at Cannes, a young woman is also struggling for autonomy in a closely knit family whose obligations threaten to subsume her. The claustrophobia is almost intolerable, as the mother’s hands keep creeping into the frame—she’s constantly trying to make improvements to her children, whose desire for autonomy is to her a betrayal akin to death. In Balagov’s highly acclaimed second film, Beanpole (2019), which won the Un Certain Regard Best Director award, love is (literally) a smothering force, as the characters try to build a life among the ruins. Set in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) following World War II and inspired by Svetlana Alexievich’s The Unwomanly Face of War, the film is a “gut punch,” in the words of critic Manohla Dargis. Running throughout both films is an undercurrent of unresolved familial and national trauma, the two strands inextricably linked.

The two are poised to infiltrate Hollywood, while staying loyal to their auteur roots and to what they learned studying at Kabardino-Balkarian State University under the great Russian Ark director, Alexander Sokurov, in their native city of Nalchik.

From left: Kira Kovalenko and Kantemir Balagov

How did you two meet? In film school?

KANTEMIR BALAGOV: We met in film school in Nalchik. Kira was there from the first year and I switched schools there in my third year, after I realized I wanted to make movies.

When was that realization?

BALAGOV: I was 19 or 20. It was after I made a web series on YouTube called Fellas, about young guys who get in trouble and start a circle of violence. A ten-part series, [each episode] five to ten minutes long.

Was there a film industry where you were growing up in the North Caucasus?

BALAGOV: No, not there. My dad just bought me a camera so I could photograph weddings and earn some money. Big weddings are very popular in the Caucasus. But on that camera you could also record video, and that’s how I got into it. Kira has another story.

KIRA KOVALENKO: I never thought about being a director. I didn’t really know it was a job. When I was about 20, I accidentally heard of Alexander Sokurov’s studio. I thought I’d go there to get a good humanities education. I didn’t watch movies, and I wasn’t really interested in them.

Sokurov was directly involved in teaching you?

BALAGOV: Yes, it was his school. He would come from St. Petersburg once or twice a month, along with other filmmakers and teachers—of literature, philosophy, acting classes, art history, cinema history and so on—to teach classes. None of the teachers were from Nalchik, for obvious reasons. There weren't any local people who could do it. The cultural levels were just very different. We moved after we were done with the program. First to Petersburg and then to Moscow.

Place is a big part of how you conceive of your movies. In Unclenching the Fists, the scarred mining town in North Ossetia where it was filmed feels like a character too. Could you talk about that?

KOVALENKO: I found the place where I filmed Unclenching the Fists by accident. I remembered having driven by it once when I’d been living in Moscow. But it’s such an expressive place and it evokes so many emotions and associations and metaphors. So I went back there on purpose. I walked around, looked at the people, at the life there, and only then did I write the script. The location itself guided me about what could happen there. The search for a personal landscape helped this story to be born.

BALAGOV: It’s not really “place” that inspires me. It’s usually some detail. Or a scene. Or something I read, and I’ll come across it and start thinking about what could have happened before or after. Then I build the place and the characters into that initial idea.

You’re working on a film set in New Jersey, right?

BALAGOV: I adapted the script Butterfly Jam, which was supposed to be shot in Nalchik, for the U.S. The story now happens in Newark, where a Circassian/Kabardinian community is based, and we are moving toward making the movie happen.

But it was originally supposed to be set in Nalchik?

BALAGOV: Yes.

![]()

Telluride, Colorado

How has the process of changing it to New Jersey been?

BALAGOV: Painless. Actually, another layer has been added to the film now because of the immigration theme. It’s about a relationship between a father and son, and now the story has changed so the father’s character immigrated to the U.S. in the early 2000s. His son is an American, born in America. And the father is an immigrant who has not been able to fully adapt to this new world. There was some fear about how well the film would work here, but people who have read it have said that it’s all very organic. So, fingers crossed.

Is this a collaboration or do you two work separately?

BALAGOV: We always work separately. We ask each other for advice, but when it comes to film we always work separately.

How long have you been here in the States?

BALAGOV: More than a year. We came here on March 24th, 2022.

And you’ve been in L.A. the whole time?

BALAGOV: Yes.

Have you done any traveling within the U.S.?

BALAGOV: No, we haven’t really traveled yet. But we really want to travel around the U.S.—especially in the South, because we both love William Faulkner, and we’re curious what it’s like.

The landscape in your films, the mountains and hills, really reminds me of the landscape of the American West.

BALAGOV: Yes, when we were in Telluride it felt like we were home. The mountains and all that. They’re a little different. They look more well-groomed here. But overall there are similarities.

You were invited as Guest Directors of the 2022 Telluride Film Festival. How was that?

BALAGOV: It was amazing. Julie Huntsinger invited us. She has been one of the few people helping us with our move here. She’s the first one who wrote to us with the words: You need to leave Russia. We had thought about it, but we had also thought, Who wants us there? What would we do there? But she convinced us, and has helped us enormously.

The Telluride Film Festival takes a special place in our hearts. The atmosphere at the festival is so unique—you can relax and enjoy movies, talk with students. We were really happy there. You can feel that this festival was created by people who really care about cinema. Tom Luddy was an incredible human being, he contained so much love and light toward filmmakers. He was a special soul.

KOVALENKO: The invitation to Telluride really supported us.

BALAGOV: Considering the situation.

What happened after you got the message from Julie Huntsinger advising you to leave Russia? Where did you go?

BALAGOV: We flew to Istanbul, from there to Yerevan, and then on to Tbilisi. In Tbilisi we found that all Mastercard and Visa debit cards would stop working outside of Russia within three days. So for three days, we, along with most of the other recently arrived Russians, drove frantically around Tbilisi in search of ATMs that still had money left in them. We were able to take some of it out, which is how we were able to recover at least some of our savings.

If you went back to Russia, would you be able to keep making movies?

BALAGOV: From the point of view of the government, we would not be able to make movies. Maybe we could make underground movies, but it’s a big question. I’m not sure. Since there is no industry in Nalchik it would be really complicated. And a lot of other factors, some very banal. Like, we have to help our parents, and we don’t know how to do anything else other than make movies. We still haven’t fully processed and realized what has happened. When it was just starting, we were going out into the street thinking that something could be changed. And then, as you slowly start to see the people who support the war are real and not just bots, something fractures inside of you. Especially when people from your region, from Nalchik, support it, it’s hard to believe.

Because they believe the propaganda?

BALAGOV: Yes, the propaganda, but also so much time has gone by already—people could find information from other sources, but for some reason they continue to believe it. How can you continue to support it after [the Bucha massacre], and believe that Bucha is a creation of the West? How do people believe that? I don’t know. But people believe it. And I wouldn’t write everything off to propaganda. There are people who believe all that, even without propaganda. I hope they’re a small minority, but they are there.

Russia has always had domestic nationalism in relation to the Caucasus, and the Caucasus has had it towards Russians. It was a theme that was never discussed. The Russia-Caucasus War was never spoken about when we were growing up. So, this unspoken thing has created domestic nationalism.

Unclenching the Fists, dir. Kira Kovalenko, 2021

This thing left unspoken is really felt in all your movies too. Especially in Closeness and in Unclenching the Fists. This trauma in the family that isn’t discussed but which sits over them.

BALAGOV: Yes, I wanted to show that in Closeness. With the recording from the Chechen War and the conversation that happens afterwards. I wanted to say that these things need to be spoken about.

It was documentary footage [of the violent execution of Russian soldiers] in Closeness?

BALAGOV: I remember when I was in school my friend brought that recording to me. I had a computer and he brought either a CD or a disk, I can’t remember. And we watched this recording. And it just crashed into me. The most surprising thing is that we watched it over and over again. It was my first encounter with death. I felt fear, the fear that it could affect us. Chechnya is near Nalchik, and as a kid I was afraid of the escalation. But I can’t say that I felt like what I was seeing was right, or any contradictory emotions. I know that Russian soldiers also treated the Chechen soldiers and civilians badly.

In your movies the characters have moral complexity, where in the same moment you can see that they are feeling contradictory emotions, and they hurt each other sometimes out of love, but it doesn’t really change the experience for the person being hurt.

BALAGOV: I think that came from Sokurov introducing us to a love of literature. It’s all from great literature, where there are no bad guys. Where it’s not black and white. And yet, right now, in reality, it is so black and white.

That’s the irony!

BALAGOV: Yeah, that sometimes those are just pretty words, but right now there is black and white.

KOVALENKO: Everything that we know professionally Sokurov gave us. We had nowhere else to get it. The roots of most of the things we think about came from him. He helped our personalities grow up, wake up.

BALAGOV: He was also a great pedagogue. He didn’t want us to just copy his style. He wanted our voices to stay unique. He never judged our work from the point of view of how he would do it, but only from a professional, objective view of what is good and bad.

What movies did you see then that influenced your style or inspired you?

KOVALENKO: I hadn’t watched many movies before going to film school. I can remember seeing bits and pieces. They used to show good movies on TV. I remember when I was 6, I watched The Piano by Jane Campion. I think that’s the first film I remember. I saw very little. The movies that really influenced me I saw in the last few years. Or when we were studying film history. I started from the beginning.

BALAGOV: I watched really different movies before I took the workshop. The first movie that I saw that amazed me was probably Marcel Carné's Port of Shadows. And then your taste changes. You have to get used to that sort of movie. It’s a lot of work, and at times it was really hard. I remember when Sokurov was showing us Cries and Whispers by Ingmar Bergman on the big screen, I fell asleep, and he noticed. At some point I opened my eyes and he was looking right at me. And after the showing he asked me how I liked the movie. I said that it was hard.

Because it moves slowly?

BALAGOV: Yeah. It’s immersive. It takes a different level of focus and perception. It’s not bubblegum. I don’t want to sound like a snob, but it was just a different movie.

From left: The Piano, dir. Jane Campion, 1993; Cries and Whispers, dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1972; Port of Shadows, dir. Marcel Carné, 1938

Kira, you mentioned that in your film Unclenching the Fists you were inspired by a line from Faulkner about how confinement was easier to take than freedom. Is there other literature, or other media, that is inspiring you?

KOVALENKO: I keep coming back to what Sokurov told us when we were finishing film school: Now you must find masters who will teach you in other areas, in literature, in painting and so on, who will help guide you from here on out. And when I picked Faulkner, I understood that he would be enough to provide inspiration for a lifetime. Each time when I read him I see something new, I understand something new. And I see that it can last me a long time.

Are there other writers that inspire you?

BALAGOV: Yes. Lots. I look at lots of different sources. One of the motifs for my new film Monica was inspired by Batman comics. I wasn’t expecting it at all. I was just reading to relax. At that moment, I was feeling stuck with my screenplay. I couldn’t figure out the direction to take my characters in. Their motivations that I thought would be enough weren’t enough. I started reading and there was a phrase—[I won’t share it because] I don’t want to spoil the plot of the next movie—and it got me thinking. And then I started remembering events that had happened with my relatives. I started to think about how they must have felt at that moment, and I was connecting it with the phrase from the comics and it all connected and joined together and poured out into the script.

.png)

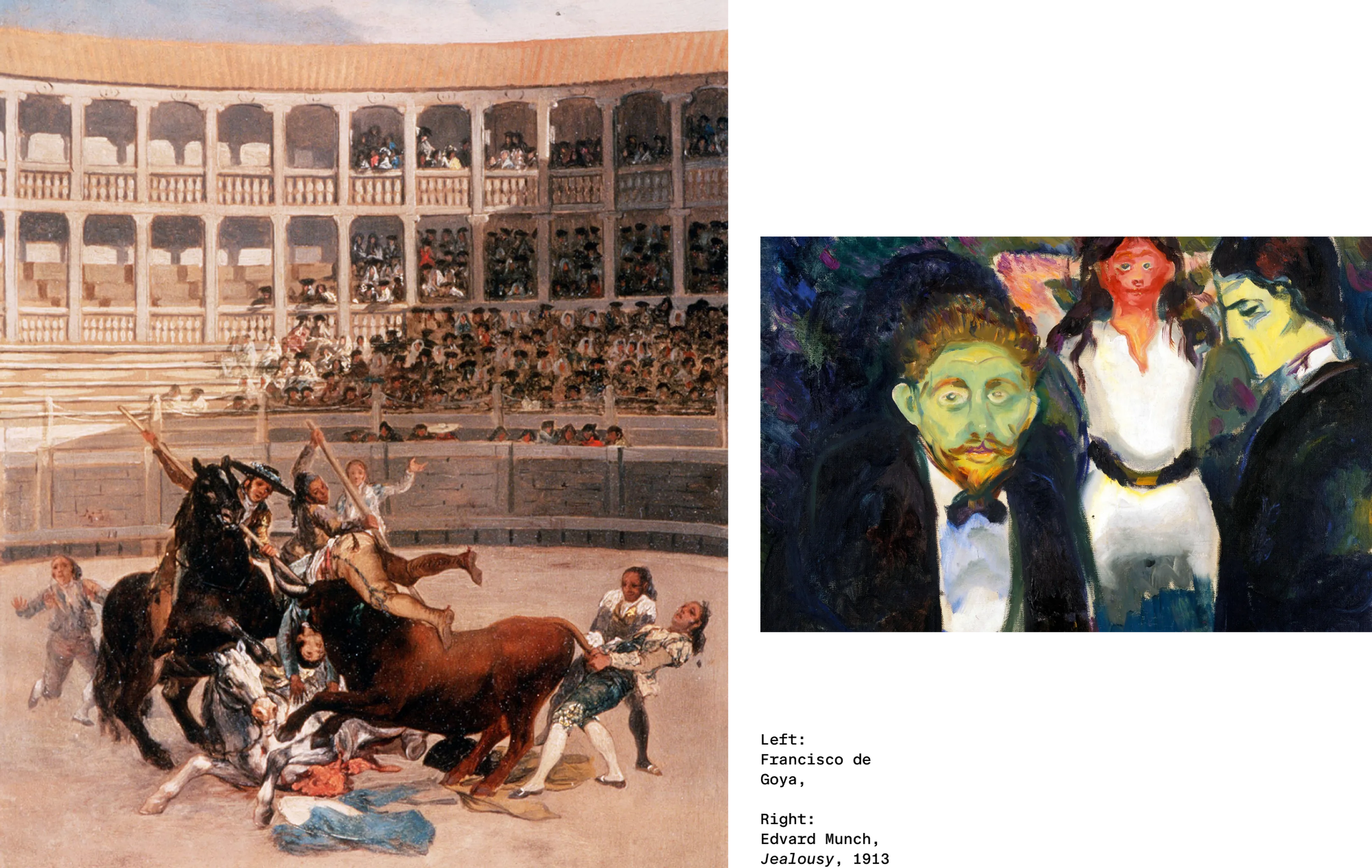

Left: Picador Caught by the Bull, Francisco de Goya, 1793

Right: Jealousy, Edvard Munch, 1913

You probably have seen a lot of Hollywood movies, and had an image of America from the movies. Now that you’re here, how does it compare to what you had imagined?

KOVALENKO: We have seen so little that it’s hard to form an image. Some little things—features, behaviors. We’re at the moment where we aren’t used to things yet, so we see things very brightly. The ways in which we are the same and the ways in which we are different.

BALAGOV: America is so diverse, and different in all the states. I often have this strange feeling here from my childhood. I keep feeling nostalgia. The smells in the streets, the weather. I can’t understand what it’s connected with. Maybe it’s the movies I saw as a child. I don’t know about other cities, but L.A. feels like it’s not in a rush. L.A. could have looked exactly the same 10 or 20 years ago. Unlike Moscow, or Petersburg, though really it’s Moscow that’s chasing modernity. In the architecture, in the services, chasing the newest technologies. And I haven’t seen that here. And because of that, I have this sense of nostalgia from my childhood. It’s very strange. Because I grew up in Nalchik. It’s a very weird feeling.

Hard to know if nostalgia is even connected to personal memories.

BALAGOV: And the little houses. We live in Santa Monica. It’s so quiet and calm, with kids on the street riding their bikes. It brings me back to my childhood, because we also had streets like that. A similar quiet. It’s all so strange. I’m still in the process of understanding what that feeling is.

KOVALENKO: Emotionally, what is happening to us doesn’t really allow us to open up and receive all of what we are experiencing here. Because however you spin it, I keep going back to Russia in my thoughts. I feel even more strongly about what is happening there, even though I’m far away. For some reason being far away amplifies it.

BALAGOV: We’re in this gray zone. In an in-between state, emotionally and physically. Reflecting on it is hard, because we’re in a state of chaos. And we don’t understand any of it.

“WE'RE IN A GRAY ZONE.

IN AN IN-BETWEEN

STATE, EMOTIONALLY

AND PHYSICALLY.”

Are you thinking about how or when you will return?

BALAGOV: There are two options. We will go back if the Butcher is gone. Of course, even if he’s gone there’s the question of who will come after him. And it’s important to work with the population, the part of the population that is infected with propaganda. And the other option is if we will be forced to go back because of financial reasons. We aren’t rich people.

You mentioned that your teacher said to pick your masters. Who inspires you visually?

KOVALENKO: For each movie you are looking for a sort of key. There isn’t just one universal one. I’ll look at Francisco Goya, Edvard Munch. The moods are very different, and you’re looking for a sort of answer. Color, visual, images—it’s different for each movie.

And for you, Kantemir?

BALAGOV: It depends on the idea. With Closeness, I was looking for inspiration in documentary photographs; in Beanpole, I looked at paintings. I might come across a documentary photograph on Pinterest or something and get stuck on it. I might look at it, and something will just pop into my head. It’s the same with video games. You might see some image and start thinking about it. Some small detail. Like a flower on a ball or something really banal, but then you start thinking about what can be made from it. And then eventually you either arrive at nothing or maybe at something interesting.

Are there any themes that you find yourself returning to from movie to movie, or does it feel resolved after you make a film about it?

KOVALENKO: I don’t think we’ve really made enough movies to be able to feel that out. But I think that some themes, like boundless love, will be a throughline or a shadow in all of our films. Someone said that they have a feeling that Kantemir and I are engaged in a dialogue with our films. Let’s see what we end up saying to one another.

“...some themes, like BOUNDLESS LOVE,

WILL BE A THROUGHLINE

OR A SHADOW

IN ALL OUR FILMS.”

Translated from Russian by Katya Apekina

_2048x0.webp)