Domestic Drama

By Max Liu

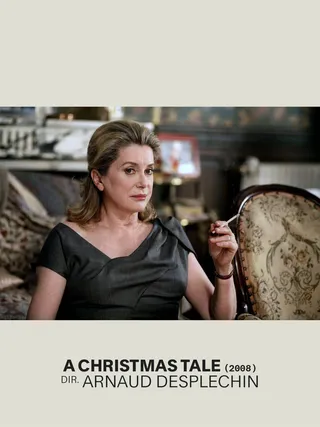

A Christmas Tale, dir. Arnaud Desplechin, 2008

Domestic Drama

The family dysfunction in Arnaud Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale conjures the epic intensity of great novels

By Max Liu

August 16, 2024

In interviews Arnaud Desplechin has talked of his desire to take a novelistic approach to filmmaking. It is as if the French auteur read the English novelist Martin Amis’s claim that “very broadly, literature concerns itself with the internal, cinema with the external,” and took it as a challenge to make films that are as concerned with his characters’ thoughts and feelings as with their actions.

![]()

![]()

The Corrections, Jonathan Franzen, 2001

In A Christmas Tale (2008), Desplechin and his co-writer Emmanuel Bourdieu use letters, diaries, readings and literary references to achieve novelistic intensity when telling the story of the Vuillards, who are as dysfunctional as literature’s most famous families, from Dostoyevsky’s Karamazovs to the Lamberts in Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections. Like the Lamberts, the Vuillards are drawn together at the family home for Christmas by an ailing parent. They fill the air with cigarette smoke and torrents of words, emotions perpetually spilling over during this rambunctious reunion at their rambling, book-lined house in Roubaix, northern France.

The ostensible reason for the family’s coming together is that Junon (Catherine Deneuve) is suffering from acute myeloid leukemia and will die without a bone-marrow transplant. The race is on to find somebody among Junon’s three grown-up children and grandchildren who can be her donor.

The middle child, Henri (a puckish Mathieu Amalric), has not seen his family for six years. In a slice of backstory at the beginning, we see Henri and his elder sister, Elizabeth, whom Anne Consigny plays as a woman caught in the vortex of midlife, as well as their father, Abel (Jean-Paul Roussillon), in court, where Henri is facing bankruptcy proceedings. Elizabeth pays off Henri’s debts and in return demands that he not contact her and stay away from family gatherings. “He is like the devil,” Elizabeth says of her brother, and there is indeed a demonic volatility about him.

My Sex Life… or How I Got into an Argument, dir. Arnaud Desplechin, 1996

We do not know exactly why Elizabeth wanted Henri gone and neither do their parents or the youngest Vuillard sibling, Ivan (Melvil Poupaud). To Henri’s dismay, his parents went along with Elizabeth’s banishment of him. He cares little for his mother, referring to her throughout as “Abel’s wife,” but loves his warm and wise father. Abel tells Elizabeth that Henri is unstable, but Elizabeth is unrepentant, saying: “I delight in his decline.”

Which Vuillard gets your sympathy may depend on your place in your own family and what stage you are at in life. When I watched A Christmas Tale at the BFI London Film Festival in 2008, I was in my twenties, already seduced by what I saw as the mercilessness of Desplechin’s earlier films My Sex Life…or How I Got into an Argument (1996) and Kings & Queen (2004). I rooted for Henri’s outrageous behavior taking a sledgehammer to the smug stories families tell about themselves. Elizabeth, I thought, was unforgiving and superficial.

Rewatching A Christmas Tale 16 years later, I felt almost exactly the opposite. I recognized some of what Elizabeth was dealing with, the maelstrom of responsibilities in her late thirties/early forties, when she worries about her mentally ill son, Paul (Émile Berling)—he suffers from paranoid hallucinations and threatens her with a knife—and her sick mother. Elizabeth has a career as a playwright, which creates more opportunities for Desplechin to depict a character immersed in literary texts, and a husband who is supportive but often appears detached. Life is complicated enough without her selfish brother dramatizing its difficulties and performing his angst. The knowledge that we are all too old for this kind of thing is written on Elizabeth’s harrowed face. She looks bonier and more fragile as the film goes on, while Henri plows deeper into the family’s pain, drinking, exploding and, during a dinner, slyly denouncing his mother as “the cunt-captain” and his sister as “the cunt-lieutenant.”

“Which Vuillard gets your sympathy may depend on your place in your own family and what stage you are at in life.”

Perhaps the setting is one reason for Henri’s behavior. The Vuillards’ house, where Abel and Junon have lived since they married in the 1960s, is as much a character as any human. Its rooms are monuments to the analogue, with Abel studying musical scores, pulling old editions of Nietzsche to read aloud, and playing records. In this theater of the family’s contested histories, the Vuillards slouch into their eternal roles. Part of Elizabeth’s frustration may be that she was catapulted into the position of eldest offspring when her brother Joseph died of leukemia at age six. Sitting alone in a room and speaking aloud, she says: “You’ve stolen my entire life.” Presumably she’s referring to her rupture with Henri, but perhaps it is more ambiguous than that—perhaps she actually means the deceased brother.

It is difficult to know who our siblings and parents are to other people. If the world sees a different Henri than the Vuillards do, that would explain how he manages to sustain a relationship with Faunia (Emmanuelle Devos), who arrives with him unexpectedly at the family home. Meeting her in the hall, Junon says: “No one has ever mentioned you.” “Nor you,” replies Faunia, indicating from the start that she is an unflappable outsider here.

Faunia and Junon go shopping together in Lille during one of the film’s well-timed breaks from the claustrophobia of the Roubaix house. They try on dresses, looking formidable and radiant in changing room mirrors. Junon says Faunia’s derriere is like Angela Bassett’s and admits she’s often wondered what Henri is like in bed. “Very enthusiastic” is Faunia’s reply, showing Desplechin can do playfulness as deftly as he does intensity.

Back at the house, the others brawl, cry, write their dark thoughts in journals. But there is also joy and generosity, gift-giving, great sweaters and dressing up for dinner; grandchildren performing a play on Christmas Eve and a visit from an elderly friend who knows family secrets; a sex scene between Ivan’s wife, Sylvia (Chiara Mastroianni), and his cousin Simon (Laurent Capelluto) that feels more like a release than a betrayal; and lots of drinking and eating in keeping with the season. The Vuillards’ appetites symbolize their aliveness. They are forever downing glasses of wine or champagne or dragging on cigarettes with an urgency in keeping with Henry David Thoreau’s imploration to “suck out all the marrow of life.”

![]()

The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, 1879-1880

![]()

Kings & Queen, dir. Arnaud Desplechin, 2004

This is in part a film that is in thrall to America, with Bassett mentioned twice; Desplechin using jazz to soundtrack the structured chaos of the family and hip-hop (albeit of an early-2000s variety that sounds quaint today) when the younger family members go to a party at the town hall; and Junon receiving Ralph Waldo Emerson’s journals for Christmas. At Joseph’s grave, Abel recites words by Emerson: “I am Defeated all the time, yet to Victory I am born.”

Desplechin is no realist. His films are set in our world, but his characters’ relationships are exaggerated versions of what happens between most people. For one thing, if the Vuillards were truly dysfunctional, they would not come together even for this Christmas, when their mother is ill. Families in which the rot is bottomless specialize in silences and standoffs that can continue down the generations, whereas the Vuillards are all noise and drama.

To my mind, My Sex Life… and Kings & Queen form a loose trilogy with A Christmas Tale. Each is nearly three hours long, each about the ultimate question of how to live, each starring Amalric and Devos. In My Sex Life…, Amalric plays Paul Dédalus, a name which recurs in Desplechin’s oeuvre (in A Christmas Tale it is the name of Elizabeth’s son) and is a reference to James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus. The Paul of My Sex Life… is a perpetual PhD student, depressed, teaching philosophy in Paris and treating women badly. Amid the confusion and paralysis of Paul’s life, Devos is again a still point, as his on-off girlfriend.

![]()

Michel Vuillermoz and Mathieu Amalric in My Sex Life… or How I Got into an Argument

![]()

Letter to the Father, Franz Kafka, 1919

In Kings & Queen, Devos plays Nora, with Amalric again in the role of her ex, this time as a manic-depressive musician named Ismaël. Nora has a young son and is also caring for her terminally ill father. He dies, leaving behind a devastating journal entry that makes Nora reevaluate her relationship with her father, and that feels like it could have been inspired by Franz Kafka’s Letter to the Father or perhaps by the bile-filled rants in Philip Roth’s novel Sabbath’s Theatre (Desplechin adapted Roth’s Deception for the screen in 2021).

We are never far from a canonical literary reference in a Desplechin film, and A Christmas Tale ends with Felix Mendelssohn’s overture from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a plaintive final note for this festive feast that teems with incident, voices and such a range of ideas and emotions that it’s a different film depending on when you watch it. Unsettlingly relatable and irresistible, it is one of the most involving depictions of a family that I have encountered in any art form.

A Midsummer Night's Dream: Overture