Jonathan Glazer’s Rebirth

By Matt Wolf

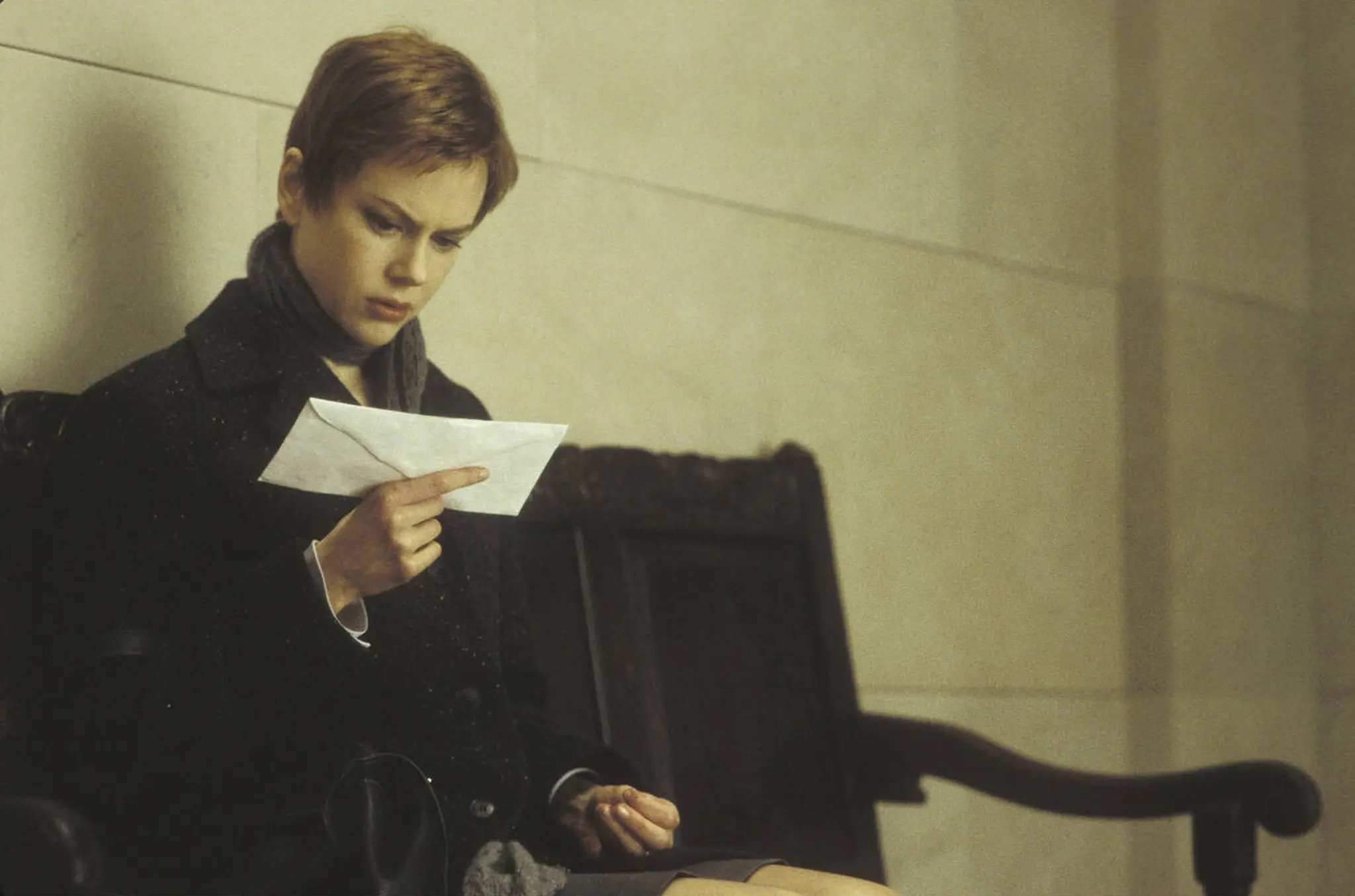

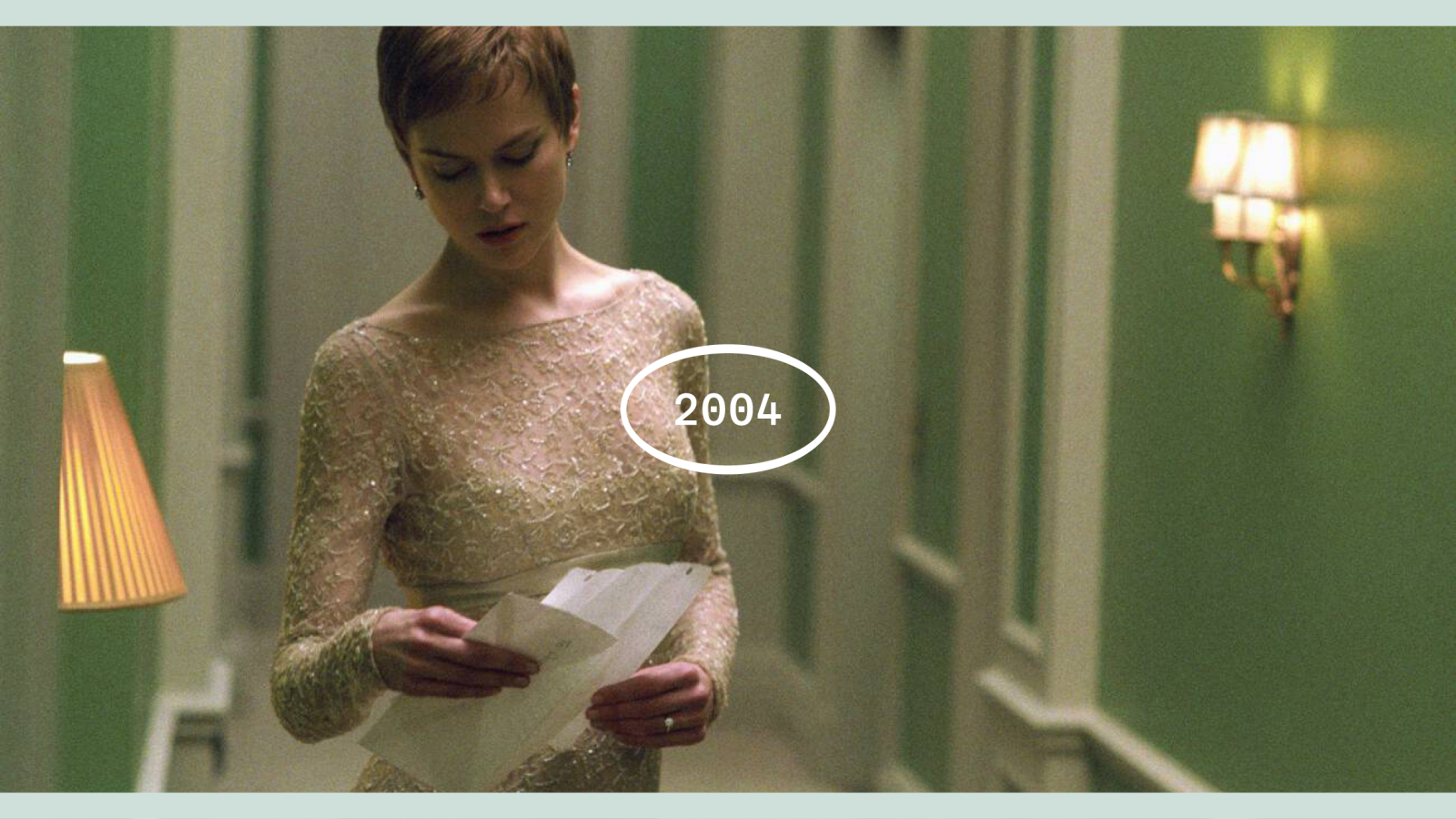

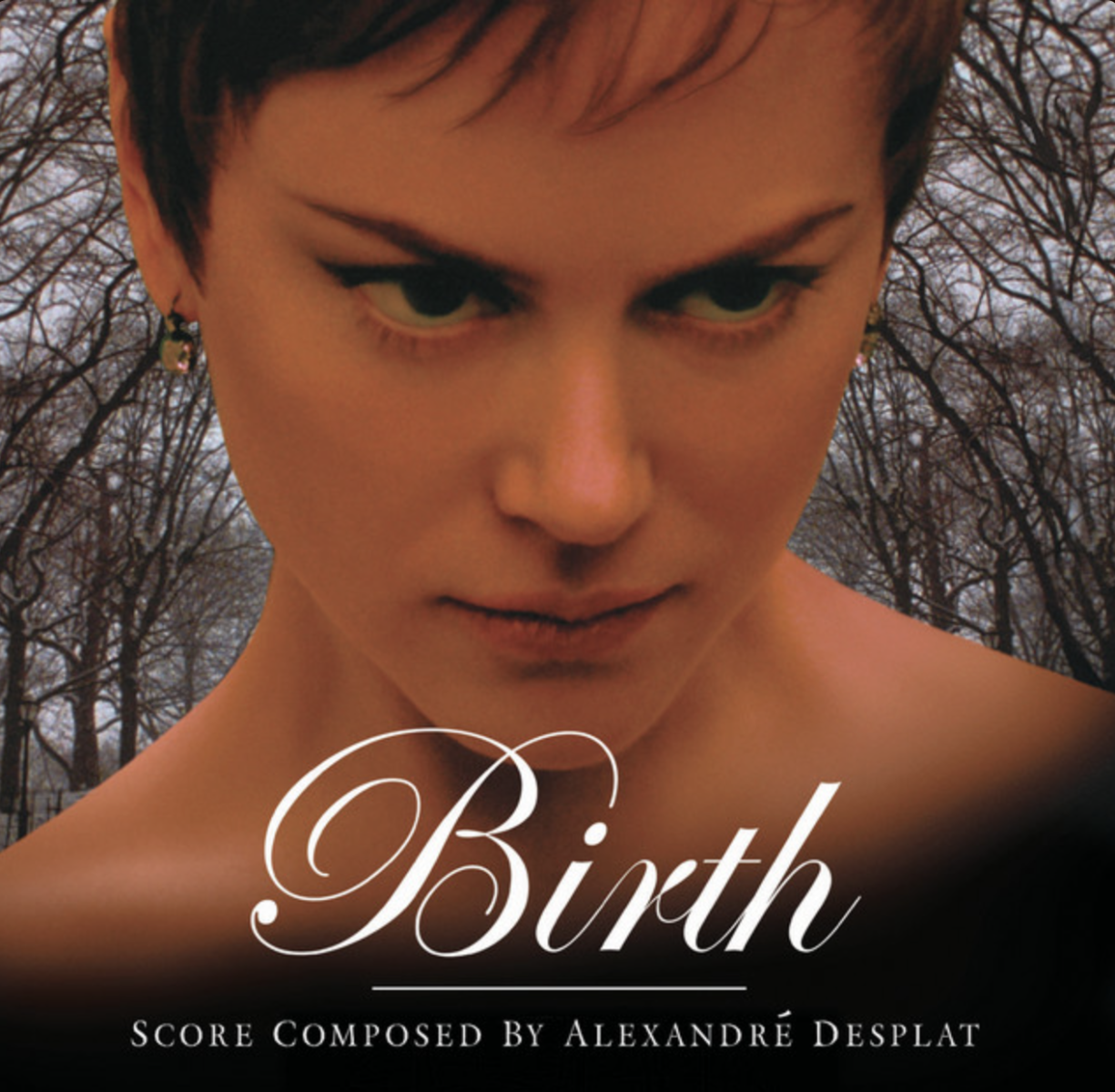

Nicole Kidman in Birth, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2004

BORN AGAIN

The psychological acuity behind Jonathan Glazer’s polarizing reincarnation drama Birth

By Matt Wolf

September 1, 2023

My boyfriend, Carl, is a couples therapist, so naturally we’re in couples therapy. A month ago we were in a session with our therapist, Mike—a crunchy fiftysomething gay man—who explained to us the concept of limerence. The idea was first introduced by the psychologist Dorothy Tennov in her 1979 book, Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love. In the book, Tennov describes the phenomena as an overpowering emotional state of obsession with another person. People experiencing limerence often have intrusive thoughts; their hearts race as they’re idealizing, or even idolizing, the object of their desire. Mike explained, “Limerence doesn’t last, and that’s why long-term relationships lose their intensity.” Carl and I looked at each other blankly but affectionately.

Scenes from Birth, starring Nicole Kidman, Cameron Bright and Lauren Bacall

Even though we are no longer in the throes of limerence, Carl and I decided to go on a date that night to see Jonathan Glazer’s critically divisive 2004 film Birth, which was playing at the Metrograph theater on New York’s Lower East Side. In the lobby of the theater we ran into a cinephile friend, who was smitten with her new boyfriend. They were both shocked that we hadn’t seen the film before, and I explained that I was waiting to watch a 35mm print on the screen (a filmmaker’s typical excuse for glaring gaps in knowledge).

Glazer is a cult figure among filmmakers. He’s known for his precise, tightly calibrated approach, and perhaps as a result of this rigor, he has only released three films to date (his fourth, the Nazi drama The Zone of Interest, debuts stateside in October). Glazer’s first feature, Sexy Beast, debuted in 2000, but I became a fan when I saw his last transfixing film, Under the Skin (2013). In it, Scarlett Johansson plays an otherworldly being—an alien, or perhaps a cyborg—who takes the form of an affectless, beautiful young woman in Scotland. Scene after scene, she methodically lures men into a paranormal black box setting, where she seductively destroys them. Johansson’s spellbinding performance is enhanced by the indie musician Mica Levi’s pulsing, atonal score.

Nicole Kidman in Birth

In a Glazer film, music is a character itself, and it’s used to mesmerizing effect. When I watch his films, I feel hypnotized, and perhaps that’s why I’m able to invest in story premises that may seem far-fetched, or in the case of Birth, farcical. The film is a love story between an adult woman and a 10-year-old boy who claims to be the reincarnation of her deceased husband.

After premiering at the Venice Film Festival in 2004, Birth was met with hostile boos. A critic forThe Washington Post described the film as “too highbrow for the multiplex and too literal for the hipsters, it’s unsatisfying both as gothic camp and serious cinema.” Other critics called the film “hilariously pretentious” and “creepy pedophilia.” While many discounted Birth as misguided art-house provocation, in the decades that followed, the film has been reappraised as an important, overlooked masterpiece.

As I sat down in the theater, I complained to Carl that the audience seemed unusually rowdy for a Wednesday night. It was nine o’clock (past my bedtime), and as a group of bros were shuffling into the row behind me, I felt agitated. Then the lights dimmed, and Alexandre Desplat’s hypnotic orchestral score faded up. All distractions receded, and I was hooked in.

Sexy Beast, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2000

At the time of Birth’s making, Desplat was a relative unknown in the U.S., having scored mainly small films in France. Since Birth, he’s won two Oscars—one for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, another for Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water—and composed music for some 100 films, from two Harry Potter sequels to Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. Yet in my mind nothing compares to his work in Birth. Most auteurs are contemptuous of a heavy-handed score, preferring the naturalistic drama of ambience. I can appreciate seasoned film viewers’ skepticism about a score that leads or manipulates the emotional response to a story. Nonetheless I’m a music-in-film lover, and Glazer—who first came to prominence as a music-video director for bands like Radiohead, Blur and Massive Attack—shares that predilection.

The film opens with a two-minute tracking shot, set to Desplat’s orchestral music, that follows a man jogging in snowy Central Park. The man, who we later learn is named Sean, reaches a tunnel, then falls to his knees and collapses. The music stops, and the film cuts to a newborn baby emerging from a pool of water. Sean dies in that passageway, but he is also reborn.

Ten years later, we meet Sean’s wife, Anna, at his tombstone on the anniversary of his death. A bewitching Nicole Kidman plays Anna with a constant look of startled unease. Her preppy and agitated fiancé, Joseph, waits in the car. Shortly after, they attend their engagement party at her family’s richly appointed Upper East Side apartment.

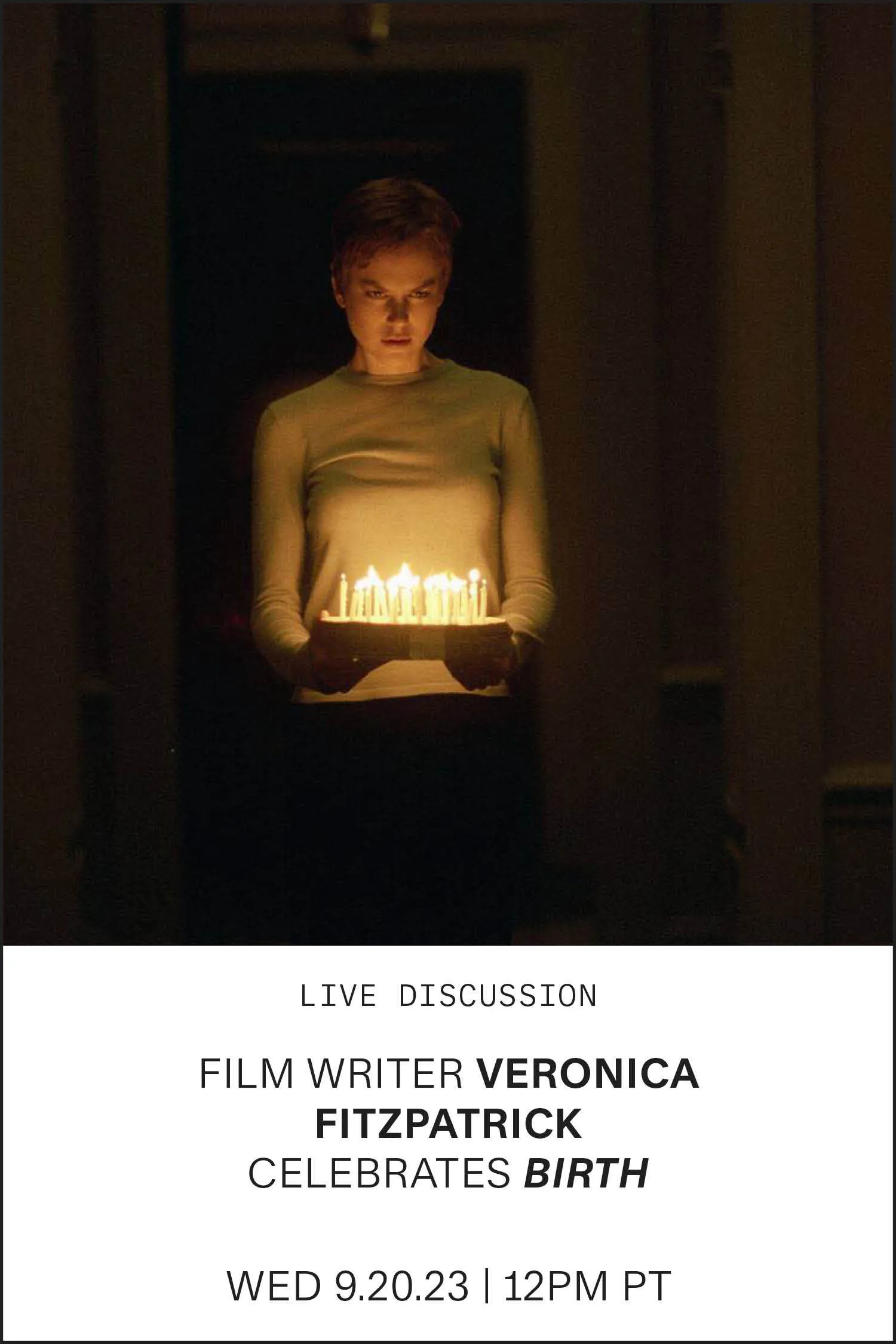

A pivotal scene soon follows, when Anna walks through her family’s apartment illuminated by dozens of birthday candles. After her mother, Eleanor (brilliantly played by Lauren Bacall), makes her wish, a solemn 10-year-old boy interrupts by announcing blankly, “I’m here to see Anna.” The family is stunned. Confused, Anna leads him to the kitchen and asks, “What do you want?” He responds with disarming confidence, “You. You’re my wife.” Anna angrily escorts the child to the door. As he leaves, the little boy warns her, “You’ll be making a big mistake if you marry Joseph.”

Under the Skin, dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2013

A spell is cast, and for the remainder of the film Anna contends with the gravitational pull she feels toward this beguiling child, who may or may not be the vessel for her great love and loss.

In a Charlie Rose interview to promote the film, Nicole Kidman says, “I feel very exposed in this role.” When Rose asks about the film’s challenging premise, she says, “I think it disturbs people, I think most people have had a love that is that powerful in their life.… [I]t’s a frightening experience because at the same time you are out of control.” What Kidman describes is the euphoria and despair of limerence. Tennov called it “an uncontrollable, biologically determined, inherently irrational, instinct-like reaction.”

That powerful state is most evocatively represented in a sequence that begins with Anna and Joseph confronting Sean’s father. “You’re hurting me,” she says to the boy, and bends down to address Sean with her piercing cat eyes, whispering, “Don’t bother me again.” As she turns around to the elevator, Desplat’s booming string score surges. Sean collapses to the floor on his knees, echoing the tortured body language of Anna’s husband as he died in Central Park.

The pulsating score grows louder as Anna and Joseph run into the symphony. They are late, climbing over the audience to find their seats in the center of the auditorium. The camera begins slowly zooming into a close-up of Anna’s face, which morphs between expressions of exacerbation, horror and relief. It’s an extraordinary cinematic depiction of limerence, made palpable by music. Anna’s true love is back.

“…an uncontrollable, biologically determined, inherently irrational, instinct-like reaction.”

As Birth continues, the relationship between Anna and Sean deepens, despite the warnings and dismay of Anna’s family and Joseph. Sean displays uncanny recall for obscure details from his previous life with Anna, and she becomes convinced that the boy is indeed her husband. As Anna’s love intrusively consumes her being, she abandons reason, and her relationship with Sean becomes uncomfortably intimate. I heard snickering behind me from the audience as Anna pointedly asks Sean, “You ever made love to a girl?”

The highlight of Desplat’s score is the music piece titled “The Kiss.” As young Sean and Anna say goodbye outside of her apartment building on a snowy night, their lips finally touch. When that startling moment occurred, the fratty bro behind me cheered and whistled. I whipped around and said, “Could you shut up? You’re ruining the film.” I heard laughter from others in the audience. The spell cast by Glazer’s finely tuned filmmaking had been broken.

Under the Skin original soundtrack by Mica Levi

Snapping out of my own limerent viewing, I recognized how far Glazer had pushed my suspension of disbelief. Whether or not this relationship was plausible, it felt emotionally true. Glazer said to Charlie Rose, “It’s the razor’s edge of the piece in a way.” Kidman adds: “She so wants to believe, and is so willing to believe. The kiss is incredibly pure.”

In the final act of the film, a chain of events unravels the veracity of Sean’s claim of reincarnation (a little too neatly for my tastes). When the boy finally leaves Anna alone, her mother says dismissively, “I never liked Sean.” Anna and Joseph marry unhappily at her family’s Hamptons beach house. In a conclusive voice-over from a letter written to Anna, Sean says plaintively, “I’ve been seeing an expert.… Mom said maybe it was a spell, but it’s a good thing that it’s gone away now.” He finishes, “I guess I’ll see you in another lifetime.”

Birth original score by Alexandre Desplat

When I left the theater, I felt like I had awoken from an unsettling dream. I posted a picture of the film’s poster on Instagram with the caption “Whoa.” When I woke up the next morning, five different filmmakers had sent me messages saying Birth is one of their favorite films. A novelist wrote to me, “I listened to that soundtrack on repeat while writing an entire book.” Perhaps it’s no coincidence that storytellers—whose craft is to cast spells, and to draw viewers and readers into unexpected emotional states—feel an affinity with Glazer’s ambitious and risky project.

I started to read more about Tennov and her theories. At the time of publication, her research was largely derided by her predominantly male psychologist colleagues. However, in the years that followed Tennov was recognized for her important contributions to the widely discussed attachment theory. She wrote, “Your limerent daydreams may be unlikely, even highly unlikely, but they retain fidelity to the possible.” However maudlin the fairy-tale premise of “everlasting love” may seem, in Birth, that wish is treated as something admirable, frightening and true. Sean lives on, in one form or another.

From left: Jonathan Glazer’s music videos for Radiohead's “Street Spirit (Fade Out),” Jamiroquai's “Virtual Insanity” and Blur's “The Universal”; and his commercials “Surfer” (for Guinness) and “Whip Around” (for Stella Artois)