Setting the Scene: Sarah Greenwood & Katie Spencer

By Yonca Talu

Barbie, dir. Greta Gerwig, 2023

Setting the Scene

From Pride & Prejudice to Barbie, the powerhouse design team of Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer conjure distinctive character-driven environments

By Yonca Talu

October 18, 2023

Nearly 30 years into their artistic partnership, production designer Sarah Greenwood and set decorator Katie Spencer are known for crafting lush, elaborate cinematic worlds that captivatingly reimagine literary classics and pivotal historical moments. From the Keira Knightley–led Jane Austen and Leo Tolstoy adaptations Pride & Prejudice (2005) and Anna Karenina (2012) to the World War II–set Winston Churchill portrait Darkest Hour (2017), Greenwood and Spencer’s long-standing collaboration with filmmaker Joe Wright is a masterful example of the duo’s ability to create character-driven sets that are as committed to verisimilitude as they are unfettered by it. With Barbie (2023), Greta Gerwig’s pink-soaked blockbuster homage to the iconic Mattel doll, Greenwood and Spencer deliver their most adventurous work yet, marrying a modernist, minimalist aesthetic with centuries-old stage traditions. The six-time Academy Award–nominated British designers both have backgrounds in theater and first crossed paths in 1995 while working at the BBC, before transitioning to cinema together. They recently spoke with Galerie via video call about the tight-knit team they form with Wright, how they breathe life into a film’s interiors and their process of moving from concept to execution.

From left: Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer

Your first projects with Joe Wright were the BBC miniseries Nature Boy [2000] and Charles II: The Power and the Passion [aka The Last King; 2003]. How did you start collaborating with him?

Greenwood: We met Joe through actress Kathy Burke, who’s a very good friend of his. We’d worked with Kathy on Patrick Marber’s August Strindberg adaptation After Miss Julie [1995], a BBC show in which she co-starred and which was also Katie’s and my first collaboration. Years later, when Joe was hired to direct Nature Boy, he was complaining to Kathy about the pale-gray male designers he’d been meeting at the BBC. And she said, ‘‘I know these brilliant young female designers, Sarah and Katie. You should meet them.’’ It was a Friday afternoon, and I was out for lunch with some friends. I was kind of hesitant, like, ‘‘Shall I go to this appointment?’’ Of course one has to go, so I went. Joe was so young at the time—not even 30. He had studied fine art and had a very good visual eye.

He’d also done some theater, hadn’t he? And he came from a family of puppeteers.

Greenwood: Yes. He was just great—he had tenacity, passion and drive. We drank a couple of glasses of wine, and it was chat, chat, chat. It was a real meeting of the minds, and now Joe is like my little brother. There’s great honesty between us, which I think you need to have in filmmaking.

Spencer: We are like a family, and like a family, we speak our minds. Sometimes that means accepting each other’s opinions with good grace, and other times it means being able to say, ‘‘That’s the most stupid idea I’ve ever heard!’’ So you move on from it and try to come up with perhaps a less stupid idea. [Laughter]

.png)

From left: interiors of Pemberley in Pride & Prejudice, dir. Joe Wright, 2005; Matthew Macfadyen as Mr. Darcy in Pride & Prejudice

What were some of the ideas you and Joe Wright discussed for his first feature, the Jane Austen adaptation Pride & Prejudice?

Spencer: For Pride & Prejudice, Joe’s big thing was casting actors who were the same age as the characters. Elizabeth Bennet is 20 in the novel, and Keira Knightley was 19 when we shot the film. In [Robert Z. Leonard’s] Pride and Prejudice [1940], Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson are too mature for their roles [as Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth]. Perhaps they should have played Lizzy’s parents, the old Mr. and Mrs. Bennet. [Laughs]

Greenwood: That’s right. The other thing was the period. At the time the BBC miniseries Pride and Prejudice [1995] was so much in people’s minds. It took place between 1811 and 1812, around when the book was published, and was hallowed ground. But I didn’t particularly like it because it lacked passion and oomph.

It didn’t take any risks.

Greenwood: Yeah. In the early days of the project, Joe and I visited the Tate museum in London. We were looking at the paintings and Joe really liked portraits of men in wigs from the 18th century. I was like, ‘‘Isn’t that period a little early for our film?’’ But Joe argued that it wasn’t because Pride and Prejudice was actually written between 1796 and 1797, over a decade and a half before its publication. So we had a brainstorm moment there, and that’s how we decided to set Pride & Prejudice in the Georgian era, which has a gutsy, physical quality to it, as opposed to the BBC version’s tight Regency-era setting.

How did you convey that sense of gutsiness in the film?

Spencer: We were very influenced by John Schlesinger’s Far from the Madding Crowd [1967], which we all watched together. You really get a sense of the exterior and interior being intermingled in that movie, which is also what Joe wanted in Pride & Prejudice.

Greenwood: In the film, the Bennet girls live on a farm and walk everywhere. For example, when they go to town, we filled the marketplace with butchers and poulterers. There were dead animals hanging everywhere, and you got the feeling that if there was blood running down the gutter, the girls would just pick up their skirts and step over it.

Spencer: Yes, the hems of their dresses were always filthy. We also did a really unusual thing with the Bennets’ house. All the animals you see in the film—pigs, ducks, cows, dogs—lived in that house for the whole shoot. There were animal handlers on set. They even had a caravan on the side, and they’d say things like, ‘‘Oh, we lost a duck last night, but we’ll get you another one!’’ [Laughter]

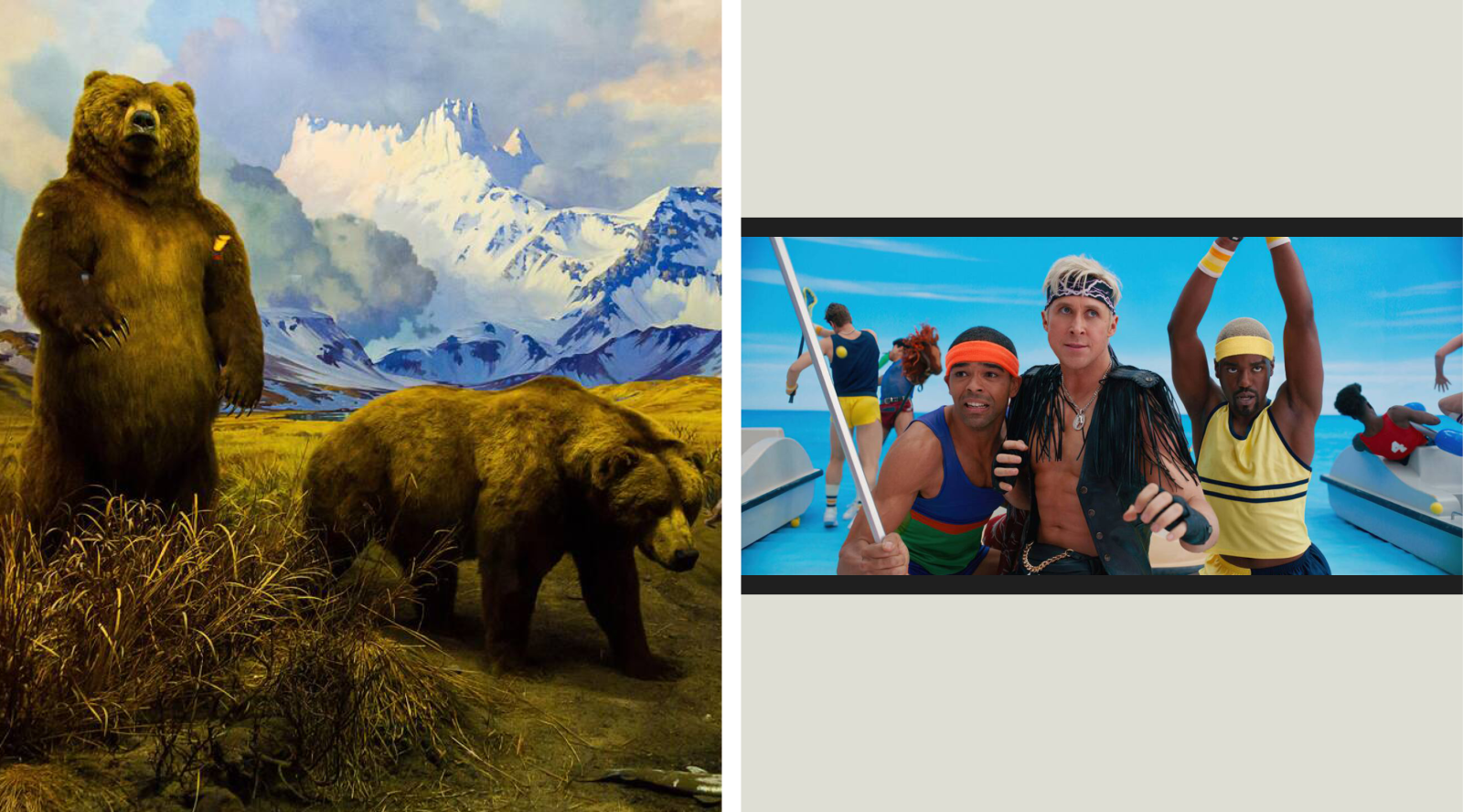

From left: Alaskan brown bear diorama in the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Kingsley Ben-Adir, Ryan Gosling and Ncuti Gatwa as Kens in Barbie

Did the actors also come and live in the house?

Spencer: Yes, the girls came and rehearsed in the house for a week. On their first day, they literally squealed around like they do in the film. They just loved it, because to them it was like time-traveling. The dogs were running around the house, too. It was exciting to see all of that. It was almost like living theater, wasn’t it?

Greenwood: Yes, it was a very exciting experience. There was a lot of freedom, and it was amazing to have that kind of fluidity and spontaneity on a period film.

How did you work out the contrast between the Bennet and Bingley residences?

Greenwood: We thought of the Bingleys as nouveau riche. You know, money’s no object to them, and everything in their house, Netherfield Park, is of the moment. I love that scene where Mrs. Bennet [Brenda Blethyn] and her daughters arrive in Netherfield. They all sit down in this immaculate house and just look so grubby and disheveled.

Spencer: And then with the Bennets’ house, we wanted it to be slightly out of fashion and out of kilter because they don’t have money like the Bingleys. Mrs. Bennet is even further outdated. She sort of froze in time when she was probably about 27.

Greenwood: That’s true. After a certain age, you kind of stop: You don’t change your hair; you don’t change your lipstick color. And it’s like Mrs. Bennet stopped, which is also visible in the way [costume designer] Jacqueline [Durran] did her dress. Her waistline is lower, and she’s all hair and bosoms.

Spencer: She also has a ridiculous French Belle bed, which nobody would have had at her age. We thought she might have gotten it as a honeymoon present or something. [Laughs]

I also love details like the cracked wall paint, which makes the Bennets’ house look even more worn-out. How much transformation did that place go through?

Greenwood: We completely took over that house [i.e., Groombridge Place in southeastern England]. It had only been filmed once before, for Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract [1982]. That movie is so perfectly framed and classical, and the garden is so beautiful. So you kind of go, ‘‘How on Earth could it be the same house?’’ But we never shot the formal gardens off to the right, and we wrecked the foreground gardens and did a lot of construction and paint work inside the house. The interior of the house was all wood-paneled, and brown was the one color we didn’t want in there. Usually you shoot the exterior of a house and build its interiors on a soundstage, but we actually built a whole set within the house. There were the real walls, and there were our walls, which we painted blue. That was expensive and laborious, but so worth it because it allowed Joe to shoot 360 degrees and follow the characters from outside to inside the house, like in the opening sequence. As you say, the paint finishes were kind of extreme. But when you think about it, the Bennets probably haven’t repainted their house for 20 years and live with servants and animals. We know what happens to our houses after a year. This is after 20 years, and the paint is all lead-based and crap. So it was about creating that lived-in quality.

Anna Karenina, dir. Joe Wright, 2012

Jumping forward, you also experimented with patina and decay in Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, which charts Winston Churchill’s early days as prime minister during World War II.

Spencer: Yes. For Darkest Hour, we took inspiration from a photograph of [British heiress] Edwina Mountbatten taken during the war. She’s wearing a brigade uniform and standing in front of her fireplace in London. She looks kind of grubby, and her house looks scuffed and mucky, with chipped paint like in Pride & Prejudice. It’s an image that perfectly encapsulates what Britain was like in the ’30s and ’40s. London was covered with a layer of filth and overwhelmed by smog. People looked more grubby than today, and everyone smoked. There was a feeling of anemia in the world.

How did you translate that historical mood into the film’s locations?

Greenwood: We tried to capture the essence of each location, be it 10 Downing Street or Buckingham Palace. We re-created both of those in derelict stately homes. Our sets feel like the real Downing Street and Buckingham Palace, but they’re actually quite different. For example, the staircase of Downing Street isn’t in the front hall, where we put it in the film. We also painted Churchill’s Downing Street bedroom pink because Joe felt like he was a big baby. [Laughs] As for Buckingham Palace, we took it down 10 stops. Historically the king and queen stayed in London during the war and were in the same boat as everybody else. So we didn’t want our Buckingham Palace to shine like a beacon.

What about Churchill’s underground War Rooms? How did you approach those?

Greenwood: The War Rooms in London are a historically preserved, amazing space. We used them as a reference for mood and texture, but we made our set bigger because we wanted it to feel like a maze. We also looked at two films about the Third Reich, the Tom Cruise movie Valkyrie [2008] and [Oliver Hirschbiegel’s] Downfall [2004]. Both films have a very ordered, cold and sharp look, which we wanted to go against in Darkest Hour. Our story was about Britain’s unpreparedness to join the war and the make-do-and-mend spirit of the War Rooms.

Spencer: I mean, it was literally like, ‘‘Okay, we’re going to set up a war room tomorrow. How many chairs have you got at home?’’ So Churchill and his colleagues brought their own chairs, which was extraordinary. But where we were completely accurate, and had to be, was the Map Room. Every map and pin in there was accurate to the day and time because it was a countdown film in a way.

I remember reading that you also took great care to re-create Churchill’s personal belongings. A lot of those, like the contents of his books and journals, weren’t even visible onscreen. They were just there to support Gary Oldman’s performance.

Spencer: That has to do with our passion for building complete environments. We don’t like making things by the yard just to fill the background. It goes back to what we did on Pride & Prejudice: We dressed the whole house. Then the actor has the freedom to grab an object and improvise with it. But it’s interesting you pick on Gary Oldman. He already knew so much about Churchill, so we couldn’t blind him with science, as it were, and had to be on top of our game. That’s why we re-created everything, from Churchill’s letters to intimate details like the cigar he smoked and the sugar cube he kept in his pocket.

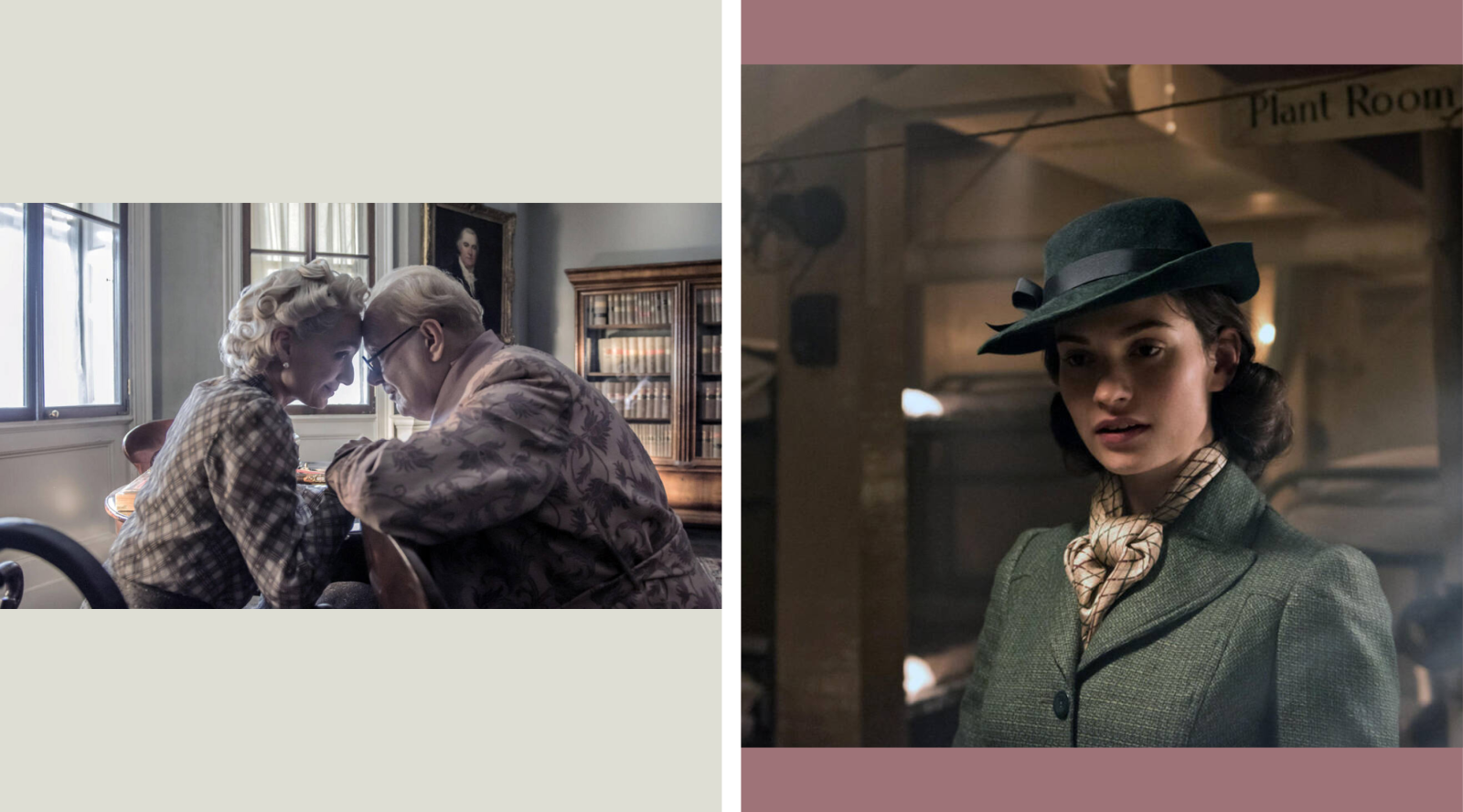

From left: Kristin Scott Thomas and Gary Oldman in Darkest Hour, dir. Joe Wright, 2017; Lily James as Elizabeth Layton in Darkest Hour

How much do you put yourself in the characters’ shoes while dressing a set? Would you say there’s a performative aspect to your process?

Spencer: We always come from character, and we do act things out between us before we bring in the director. We run through the action to make sure the set works.

Greenwood: I remember the opening shot of [Joe Wright’s] Atonement [2007], in which the camera pulls back from the dollhouse and follows the toy animals on the floor up to Briony [Saoirse Ronan] at her desk. I think we were always going to start with the dollhouse, but the toy animals were Katie’s creation. The set was done and we were waiting for Joe to arrive. Katie was bored, so she sat on the floor and played with those toy animals for two hours. She was in little Briony’s head, and she created this Noah’s ark of animals across the floor. When Joe walked in, he was like, ‘‘Oh my God, that’s it! We’ve gotta have that. We’ve gotta have that.’’ But of course we weren’t shooting that scene that day. Three weeks later, Katie and I were working on another set for the film somewhere else, and we got a phone call from Joe, who said, ‘‘I want you here to put the animals back.’’ We were like, ‘‘Well, you photographed them. You know what they look like.’’ And he was like, ‘‘No! I want you here to put the animals back across the floor.’’ [Laughter]

Spencer: That was a very embarrassing moment. Everyone was watching me as I was aligning those animals on the floor. Such a work of genius! [Laughs]

Since your approach is so character-specific and true to life’s imperfections, I wonder how you tackled the immaculate world of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, which is inhabited by archetypal dolls with little to no interiority. Was designing that movie more of a conceptual undertaking for you?

Greenwood: Completely. Barbie is the most conceptual and intellectual film we’ve ever done. It was so different, and you’ve absolutely hit the nail on the head, saying that they’re dolls. They are dolls—they are Mattel dolls—and it took us a long time to figure out what that meant. Because even Greta, who [co-]wrote the script [with Noah Baumbach], didn’t know.

Spencer: The script was fascinating. It wasn’t written to begin with like a film script. It had no scenes or anything.

Greenwood: Yes, the first line was ‘‘Don’t worry about the fact that this script is 140 pages long because all the actors are going to speak very fast.’’ [Laughter] So we were dealing with something completely bonkers, and our job was to try and get inside Greta’s head.

How did you go about that?

Greenwood: We knew we were doing the movie back in January 2021. Before we started proper prep in September, we had weekly Zoom calls with Greta. Sometimes Jacqueline [Durran] and [hair and makeup artist] Ivana [Primorac] would also join us, and we’d have amazing conversations. One of the things we talked about was a child’s experience of getting a Christmas present. It’s a big box. You rip it open and pull out the present. But you’re slightly disappointed, like, ‘‘Ugh.’’ What we wanted was for Barbie Land to be the present inside the box that’s even better than the box itself. It had to be beautiful to a kid and full of joie de vivre.

What else did you talk about?

Greenwood: We also talked about the nature of dolls. What is a doll? What makes a doll doll-like? For example, Greta brought up the scene where Ken [Ryan Gosling] and Barbie [Margot Robbie] go in for a kiss. They just don’t know what they’re supposed to do and have that beautiful pause. It’s a moment that epitomizes their doll-ness. Also, the Barbies don’t use stairs: They go to the top of their Dreamhouses and jump off. You see that enough times so that it becomes a Brechtian thing where you go, ‘‘Okay, they’re dolls.’’

Margot Robbie in Barbie

“We are like a family, and like a family,

we speak our minds.

Sometimes that means accepting each other’s opinions with good grace, and other times it means being able to say,

‘That’s the most stupid idea I’ve ever heard!’’’

What went into creating the Dreamhouses?

Greenwood: We started with buying a Dreamhouse and playing with it. We never had a Dreamhouse growing up, and we realized that when you put Barbie’s hand up inside, she can touch the ceiling. There’s something weird about the scale, which also goes for Barbie’s car. She doesn’t fit into her car—it’s too small for her because her feet are pointed. That basically led us to make the Dreamhouses in the film, as well as Barbie’s car, 23 percent smaller than reality. While the average ceiling is eight, nine feet high, our ceilings were seven and a half feet high, which made the actors look bigger in the space. But as far as things like Barbie’s hairbrush, lipstick and toothbrush are concerned, we made them bigger than life-size because they had to feel like toys.

Spencer: I remember we also talked about how children put their toys in the wrong place. So we initially thought that maybe Barbie’s bed could be in the middle of her room. But then we realized that since Kendom [which turns Barbie Land upside down] was coming up later in the film, Barbie had to have a perfect Dreamhouse in which she lived perfectly.

Greenwood: Yes, it had to be tangible, recognizable and appealing. When people came on set, a lot of them were like, ‘‘Oh my God, I had a Dreamhouse just like that.’’ And we were like, ‘‘Nope, you didn’t.’’

Spencer: ‘‘You feel like you did.’’

Greenwood: Exactly. It has the sense of a Mattel Dreamhouse, but it’s very much an interpretation.

In a way, Barbie is also your most pared-down work.

Spencer: Yes. It’s the absence of things that makes Barbie work so well, from the literal absence of walls in the Dreamhouses to the world itself.

Greenwood: It’s a world that has no water, no air, no wind, no rain. There’s no electricity or food. There’s no black and white. There are no metals. For us, who are used to working with so much layering, patina and darkness, it was really hard to go so raw, with pure colors and nowhere to hide on this 360-degree set. I think we had a breakthrough when we started thinking of Barbie Land as a diorama. Take the [Alaskan brown bear] diorama in [New York’s] American Museum of Natural History. There are two three-dimensional bears, and about 10 feet behind them, there’s a painted sky. And somewhere between the bears in the foreground and the sky in the background, there’s an incredible false perspective. The diorama goes from three-dimension to two-dimension to two-dimension to flat, which is also what we did in Barbie Land. The Dreamhouses are surrounded by an 800-foot-long and 50-foot-high painted sky. In front of the sky are layers of mountains amazingly painted in purple and ginger, and in front of the mountains are palm trees, which are all in perspective. Then you hit the wall [delineating Barbie Land], and everything becomes three-dimensional.

You had already used classical techniques like painted backdrops on Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina, which takes place in a run-down theater built on a soundstage.

Greenwood: Heavens, that was, again, very complicated. We don’t choose the easy way out, that’s for sure. [Laughs] The story of Anna Karenina is that we were initially going to do it relatively conventionally. We were going to shoot in Russia for six weeks and in Britain for another six weeks. We went to Russia in the winter to get a feel of the country, and it was absolutely breathtaking and so different from Britain. But the costs of working in Russia kept going up, and it eventually became inconceivable for us to shoot there. We thought about shooting in Britain instead, but it wasn’t possible to make Britain look like Russia on such a tight budget. We were about to lose the film, truth be told. It was then that Joe and I scouted Alexandra Palace, the derelict theater in London. Joe loved it, and we were going to use it in a scene. Then Joe phoned me up one night and said, ‘‘Think about this, Sarah. We build a theater in a studio and shoot the whole film there.’’ I was like, ‘‘Hmm, okay, right.’’ He described how one of the most difficult sequences, the [indoor] horse race, would work, and he said, ‘‘Do you think we could do it?’’ You know, I’m always up for a challenge, so I was like, ‘‘Yeah, let’s talk about it.’’

From left: Groombridge Place in Kent, England; Cabinet War Rooms in London, England; Alexandra Palace in London, England

How did you and Joe Wright develop his new concept from there?

Greenwood: We locked ourselves in a room. We had amazing books we’d brought back from Russia and our knowledge of everything we’d seen there, including the incredible paintings of [19th-century realist painter] Ilya Repin. We literally developed Joe’s new concept in a week, then presented it to [the film’s screenwriter] Tom Stoppard. He remained silent and finally just said [she imitates Stoppard’s thunderous voice], ‘‘I’ll add one line [to the script]!’’ And that was ‘‘This all takes place in a derelict theater.’’ [Laughter] That was it! We moved to Shepperton Studios and had only 12 weeks until the shoot. So we started building the sets before we’d even drawn them.

Spencer: That took a lot of blind faith on the part of the producers, Working Title Films and StudioCanal. They had faith that Joe could pull this off right, in the same way that Warner Bros. Pictures didn’t understand what we were getting at with Barbie but had to have faith in Greta.

Greenwood: Yeah. The most important thing we all had to do on Anna Karenina was to remind each other of what we were trying to accomplish, because you lost the plot at some point. You could stand there going, ‘‘I don’t understand this.’’

Spencer: Nothing was what it seemed to be. For example, the theater’s prop room was supposed to stand in for the Oblonskys’ drawing room, which was really tricky. We were like, ‘‘So what are they going to be sitting on?’’ [Laughs]

How did you orchestrate the live scene changes, in which dancing extras replace one set with another in swift-moving long takes?

Spencer: We collaborated with choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, whom we also worked with on [Joe Wright’s musical film] Cyrano [2021]. We wanted to explain how the theater is used in the film and show the physical scene changes that have to happen to take you from one set to another, whether through a cloth being lifted from the background or walls coming in to form a restaurant.

Greenwood: Yes, they are illustrative sequences. It’s like in Barbie: You know they’re dolls because such-and-such happens, and in Anna Karenina, you know you’re in a theater because that happens. And there are less and less of those in-camera changes as the film goes on because you don’t need them anymore. You kind of got that you’re in a theater and that you’re not just on the stage—you’re in the whole theater space: the substage, the fly floor, etc.

You also shot a few sequences of Anna Karenina in Russia, didn’t you?

Greenwood: Yes, we shot sequences with Levin [Domhnall Gleeson] on Kizhi Island in Russia. Levin is the only true spirit and honest character in Anna Karenina. He’s like Tolstoy’s authentic voice. That meant that he could go back out into the real world. Hence that scene where the theater doors open and Levin walks into Russia, where he eventually also takes his wife, Kitty [Alicia Vikander].

Spencer: I remember Kitty and Levin’s wedding troika initially looked like something out of the supermarket! There we were in Russia, the land of sleighs, and that troika looked like Santa Claus should be on it. [Laughs] But we covered it with lace, and it had three beautiful horses.

Greenwood: It did, and Kizhi Island was so beautiful, even though the temperature was like minus-40 degrees Celsius and there were wolves. [Laughs] That’s the thing about working with Joe—we have the most incredible adventures and really push it to the wire in every sense of the word.