David Lynch's Suburban Fantasy

By Daniel Lefferts

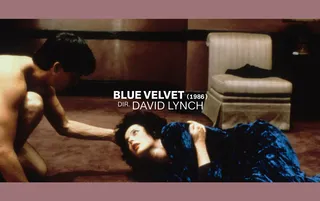

Blue Velvet, dir. David Lynch, 1986

David Lynch’s suburban fantasy

Red ants on the cherry tree and other threats to middle-class Americana

By Daniel Lefferts

April 4, 2025

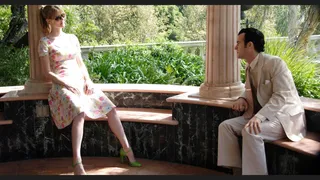

The director David Lynch left our world earlier this year, but it’s a testament to the singularity of his vision that he never seemed entirely in the world to begin with. In his films, among them the contemporary classics Blue Velvet (1986), Mulholland Drive (2001) and Inland Empire (2006), he repurposed familiar scenarios—the Hollywood story, the detective story—with the strangeness of an alien intelligence that’s often insufficiently described as “surreal.” Lynch famously practiced Transcendental Meditation and believed, as he told an audience in 2005, that “there’s an ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness inside each one of us.” He once tweeted that after a weekend of deep contemplation he’d come to the conclusion that he was “connected to the moon.”

The Lynchian double vision of reality in Blue Velevet

Yet, for as out there as he could seem, Lynch cherished the recognizable artifacts of the everyday world. He filled his films with pies, highways, landline telephones, diners and other staples of 1950s iconography. He loved America, in all its degradation and innocence, and his films are nothing if not epics of the American subconscious: dramas of wholesome sweethearts beset by dark underworlds and sexual perversion; phantasmagorias of heavenly and hellish visions that capture the nation’s most vigorously suppressed anxieties.

Chief among those anxieties is the idea of social class. Lynch would likely never have said that his films were “about” class, any more than he’d say that they were about the film industry or gender, but the American dreams and nightmares he depicts constantly derive their force from notable class signifiers. One of the reasons his films, for all their inscrutability, feel true is that they play on our economic desires and terrors.

Lynch grew up in the solid middle-class promised land that he would go on to romanticize (1999’s The Straight Story) and disrupt (the spiraling galaxy of Twin Peaks). His father’s job as a U.S. Department of Agriculture research scientist took his family all over the country, but Lynch’s circumstances, in his telling, were always idyllic. “My childhood,” he once said, was “blue skies, picket fences, green grass, cherry trees. Middle America as it’s supposed to be. But on the cherry tree there’s this pitch oozing out…and millions of red ants crawling all over it. I discovered that if one looks a little closer at this beautiful world, there are always red ants underneath.”

Mulholland Drive, dir. David Lynch, 2001

In Lynch’s films, the disturbance underneath the “beautiful world” often takes the form of dangerous precarity: a poverty, or criminality, that threatens the characters’ sense of security and—perhaps even more distressingly—tantalizes them with its forbidden, ugly truths. The famous opening scene of Blue Velvet, in which a portrait of a cheerful all-American suburban neighborhood gives way to a close-up of dark beetles squirming under the grass, harks back to Lynch’s red ants. It also offers a metaphor for the journey the film’s protagonist, Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan), will soon set out on. As he becomes entangled with a mysterious club singer, Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini), and her network of psychopathic handlers, Jeffrey leaves the blissful confines of his middle-class youth for another world: one that is stranger, more sordid, and more enticing than his own, and, not incidentally, further down the socioeconomic ladder.

Perhaps the first sign that Dorothy belongs to a world of trouble is that she lives in an apartment, in a neighborhood that Jeffrey’s aunt has warned him to stay away from and where men hoot from their cars at passing women. Geographically Jeffrey isn’t far from home, but demographically he couldn’t be more distant from the tree-lined suburban street where he and his good-girl crush, Sandy (Laura Dern), take romantic nighttime strolls. In his visits to Dorothy’s apartment, Jeffrey will witness alternately terrifying and intoxicating things—drug use, battery, sexual slavery, a shadow society and a shadow economy built on illicit trade, exploitation and murder—all within an environment rife with the trappings of the low-down: dingy interiors, malfunctioning elevators, coarse language. Lynch points up the film’s contrasting atmospheres with a vivid color palette. Compare the deep, lurid hues of Dorothy’s furnishings and apparel with the pastel pinks and floral patterns favored by Sandy.

Inland Empire, dir. David Lynch, 2006

Jeffrey struggles to keep these two worlds—good and bad, honest and corrupt, bourgeois and disreputable—apart. In time they collide. When, late in the film, Jeffrey, Sandy and a group of high-school boys find Dorothy standing, naked and bruised, on Jeffrey’s lawn, the image is disturbing not only because of Dorothy’s state but also because her presence on the tree-lined suburban street is socioeconomically uncanny. In exhibiting her abjection in a place where she doesn’t belong, Dorothy acts as a sudden disruption of the downtrodden—a return of the low-class repressed—into a paradise of Reagan-ite prosperity. One of the implicit questions posed by the film, and by this startling scene in particular, is whether Dorothy’s world is only a nightmare briefly perturbing the “real” world, or whether she is in fact an ambassador of reality and it’s Jeffrey and Sandy’s world that’s merely a dream.

As his career progressed, Lynch revisited the archetype of innocent middle-class America, albeit through an increasingly nostalgic lens, as if the world of stable families and well-tended lawns was already bygone. In the television series Twin Peaks (1990–1991), that anodyne world turns out to be the source of evil—Laura Palmer’s killer literally comes from inside her own home—suggesting that the criminal and sexual iniquities of society have terminally infected the middle class, rotting it from the inside out. In Mulholland Drive, the heroine (Naomi Watts) has all the hallmarks of a darling from the American heartland—angelic smile, buttoned cardigan—but in fact she hails from Canada. In Inland Empire, Lynch’s final feature film, and arguably his most powerful, the fantasy of middle-class America has disappeared altogether, replaced only by decadent wealth and hideous poverty.

No serious person pretends to know exactly what “happens” in Inland Empire, but a rough outline is as follows: a Hollywood actress, Nikki (Laura Dern), lands a coveted role in a film only to learn that the film is cursed. After an affair with a fellow cast member and a psychotic break, in which she confuses the film’s script for reality, Nikki enters a kind of schizophrenic, shattered-ego landscape, journeying through different selves with different lives in different places, before returning to some reconstituted, possibly more enlightened version of the person she once was.

“They become larger individuals, they inhabit more fully the truth of America, after their brief tours of the degenerate underground.”

If there is any rhyme or reason to the progression of this journey, it’s one of downward mobility. We first meet Nikki in her palatial old-money Los Angeles home, where she receives an ominous visit from an older woman who purports to be a neighbor. When asked which house she lives in, the visitor replies, in a menacing tone redolent of class resentment, that it’s “tucked back in the small woods—the brick house.” It’s our first clue that Nikki’s journey will involve not only contact with other selves but contact with lower economic stations. (In Blue Velvet, Dorothy’s apartment building is also brick—the construction material of cities, decaying industry, transient and precarious living arrangements, and therefore, in the Lynchian universe, of danger.)

In her various iterations, Nikki will find herself associating with prostitutes; she’ll find herself living in a shabby house with a husband who consorts with ne’er-do-wells; she’ll seek help from a mysterious man in a dark office, recounting episodes of abuse in a manner of speech far removed from the prim diction she uses when we first meet her. (“Fucker had a dick like a rhinoceros,” she says of a former lover. “He’d fuck the shit out of you, I’ll tell you what.”) Near the end of the film, she’ll stumble down Hollywood Boulevard, delirious and bleeding from a stab wound, before collapsing in a small homeless encampment, where a drifter holds the flame of a Bic lighter to her face as she dies. Only after reaching this low—wasting away on the streets, the ultimate American humiliation—does she commence her return to her “real” self, and her mansion.

As he does for Jeffrey and Sandy in Blue Velvet, Lynch gives Nikki a happy ending, and that artistic choice has an integrity and a moral beauty. But it doesn’t read as entirely convincing, and I don’t think it’s supposed to. Lynch knows as well as we do that the nightmare—in all its terror, and in all its seduction—remains. In their respective journeys Jeffrey and Nikki learn that, as much as they take their stability and comfort for granted, another world lies beneath their feet, and that the ground can always fall out from under them. They also learn that that world contains revelations without which they could only ever be partial people. They become larger individuals, they inhabit more fully the truth of America, after their brief tours of the degenerate underground.

![]()

Priscilla Pointer and Kyle MacLachlan in Blue Velvet

![]()

David Lynch in Kiev, 2017

Lynch died during the time of the Los Angeles wildfires, a disaster that, like all climate catastrophes, will have staggeringly different consequences for the rich and poor in Los Angeles and beyond. He also died four days before the inauguration of the current president and his billionaire advisers, whose regressive tax-break proposals and hacksawing of social services threaten to make the middle-class American dream even more unrealizable.

In Lynch’s work, that dream, so central to our national self-conception, is always vulnerable to disruption, always, in the sheer surrealism of its beauty, partly a fantasy. But now it is literally, materially, a fiction. The street in Wilmington, North Carolina, that Lynch used for the exterior of Jeffrey’s house in Blue Velvet is lined with properties that, according to current Zillow estimates, mostly go for around half a million. In today’s world, Jeffrey’s father, a humble hardware-store owner, would more likely raise his family in Dorothy’s dreaded brick apartment building than in the picturesque suburban neighborhood to which Jeffrey, after his brush with the netherworld, happily returns.

“I’m seeing something that was always hidden,” Jeffrey tells Sandy. “I’m in the middle of a mystery.” In the coming era, for better or worse, many more of us may see what was always hidden too.